Source: https://getpocket.com/explore/item/the-empty-brain

Archive: https://archive.vn/3JHkH

No matter how hard they try, brain scientists and cognitive psychologists will never find a copy of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony in the brain – or copies of words, pictures, grammatical rules or any other kinds of environmental stimuli. The human brain isn’t really empty, of course. But it does not contain most of the things people think it does – not even simple things such as ‘memories’.

Our shoddy thinking about the brain has deep historical roots, but the invention of computers in the 1940s got us especially confused. For more than half a century now, psychologists, linguists, neuroscientists and other experts on human behaviour have been asserting that the human brain works like a computer.

To see how vacuous this idea is, consider the brains of babies. Thanks to evolution, human neonates, like the newborns of all other mammalian species, enter the world prepared to interact with it effectively. A baby’s vision is blurry, but it pays special attention to faces, and is quickly able to identify its mother’s. It prefers the sound of voices to non-speech sounds, and can distinguish one basic speech sound from another. We are, without doubt, built to make social connections.

A healthy newborn is also equipped with more than a dozen reflexes – ready-made reactions to certain stimuli that are important for its survival. It turns its head in the direction of something that brushes its cheek and then sucks whatever enters its mouth. It holds its breath when submerged in water. It grasps things placed in its hands so strongly it can nearly support its own weight. Perhaps most important, newborns come equipped with powerful learning mechanisms that allow them to change rapidly so they can interact increasingly effectively with their world, even if that world is unlike the one their distant ancestors faced.

Senses, reflexes and learning mechanisms – this is what we start with, and it is quite a lot, when you think about it. If we lacked any of these capabilities at birth, we would probably have trouble surviving.

But here is what we are not born with: information, data, rules, software, knowledge, lexicons, representations, algorithms, programs, models, memories, images, processors, subroutines, encoders, decoders, symbols, or buffers – design elements that allow digital computers to behave somewhat intelligently. Not only are we not born with such things, we also don’t develop them – ever.

We don’t store words or the rules that tell us how to manipulate them. We don’t create representations of visual stimuli, store them in a short-term memory buffer, and then transfer the representation into a long-term memory device. We don’t retrieve information or images or words from memory registers. Computers do all of these things, but organisms do not.

Computers, quite literally, process information – numbers, letters, words, formulas, images. The information first has to be encoded into a format computers can use, which means patterns of ones and zeroes (‘bits’) organised into small chunks (‘bytes’). On my computer, each byte contains 8 bits, and a certain pattern of those bits stands for the letter d, another for the letter o, and another for the letter g. Side by side, those three bytes form the word dog. One single image – say, the photograph of my cat Henry on my desktop – is represented by a very specific pattern of a million of these bytes (‘one megabyte’), surrounded by some special characters that tell the computer to expect an image, not a word.

Computers, quite literally, move these patterns from place to place in different physical storage areas etched into electronic components. Sometimes they also copy the patterns, and sometimes they transform them in various ways – say, when we are correcting errors in a manuscript or when we are touching up a photograph. The rules computers follow for moving, copying and operating on these arrays of data are also stored inside the computer. Together, a set of rules is called a ‘program’ or an ‘algorithm’. A group of algorithms that work together to help us do something (like buy stocks or find a date online) is called an ‘application’ – what most people now call an ‘app’.

Forgive me for this introduction to computing, but I need to be clear: computers really do operate on symbolic representations of the world. They really store and retrieve. They really process. They really have physical memories. They really are guided in everything they do, without exception, by algorithms.

Humans, on the other hand, do not – never did, never will. Given this reality, why do so many scientists talk about our mental life as if we were computers?

In his book In Our Own Image (2015), the artificial intelligence expert George Zarkadakis describes six different metaphors people have employed over the past 2,000 years to try to explain human intelligence.

In the earliest one, eventually preserved in the Bible, humans were formed from clay or dirt, which an intelligent god then infused with its spirit. That spirit ‘explained’ our intelligence – grammatically, at least.

The invention of hydraulic engineering in the 3rd century BCE led to the popularity of a hydraulic model of human intelligence, the idea that the flow of different fluids in the body – the ‘humours’ – accounted for both our physical and mental functioning. The hydraulic metaphor persisted for more than 1,600 years, handicapping medical practice all the while.

By the 1500s, automata powered by springs and gears had been devised, eventually inspiring leading thinkers such as René Descartes to assert that humans are complex machines. In the 1600s, the British philosopher Thomas Hobbes suggested that thinking arose from small mechanical motions in the brain. By the 1700s, discoveries about electricity and chemistry led to new theories of human intelligence – again, largely metaphorical in nature. In the mid-1800s, inspired by recent advances in communications, the German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz compared the brain to a telegraph.

Each metaphor reflected the most advanced thinking of the era that spawned it. Predictably, just a few years after the dawn of computer technology in the 1940s, the brain was said to operate like a computer, with the role of physical hardware played by the brain itself and our thoughts serving as software. The landmark event that launched what is now broadly called ‘cognitive science’ was the publication of Language and Communication (1951) by the psychologist George Miller. Miller proposed that the mental world could be studied rigorously using concepts from information theory, computation and linguistics.

This kind of thinking was taken to its ultimate expression in the short book The Computer and the Brain (195 , in which the mathematician John von Neumann stated flatly that the function of the human nervous system is ‘prima facie digital’. Although he acknowledged that little was actually known about the role the brain played in human reasoning and memory, he drew parallel after parallel between the components of the computing machines of the day and the components of the human brain.

, in which the mathematician John von Neumann stated flatly that the function of the human nervous system is ‘prima facie digital’. Although he acknowledged that little was actually known about the role the brain played in human reasoning and memory, he drew parallel after parallel between the components of the computing machines of the day and the components of the human brain.

Propelled by subsequent advances in both computer technology and brain research, an ambitious multidisciplinary effort to understand human intelligence gradually developed, firmly rooted in the idea that humans are, like computers, information processors. This effort now involves thousands of researchers, consumes billions of dollars in funding, and has generated a vast literature consisting of both technical and mainstream articles and books. Ray Kurzweil’s book How to Create a Mind: The Secret of Human Thought Revealed (2013), exemplifies this perspective, speculating about the ‘algorithms’ of the brain, how the brain ‘processes data’, and even how it superficially resembles integrated circuits in its structure.

The information processing (IP) metaphor of human intelligence now dominates human thinking, both on the street and in the sciences. There is virtually no form of discourse about intelligent human behaviour that proceeds without employing this metaphor, just as no form of discourse about intelligent human behaviour could proceed in certain eras and cultures without reference to a spirit or deity. The validity of the IP metaphor in today’s world is generally assumed without question.

But the IP metaphor is, after all, just another metaphor – a story we tell to make sense of something we don’t actually understand. And like all the metaphors that preceded it, it will certainly be cast aside at some point – either replaced by another metaphor or, in the end, replaced by actual knowledge.

Just over a year ago, on a visit to one of the world’s most prestigious research institutes, I challenged researchers there to account for intelligent human behaviour without reference to any aspect of the IP metaphor. They couldn’t do it, and when I politely raised the issue in subsequent email communications, they still had nothing to offer months later. They saw the problem. They didn’t dismiss the challenge as trivial. But they couldn’t offer an alternative. In other words, the IP metaphor is ‘sticky’. It encumbers our thinking with language and ideas that are so powerful we have trouble thinking around them.

The faulty logic of the IP metaphor is easy enough to state. It is based on a faulty syllogism – one with two reasonable premises and a faulty conclusion. Reasonable premise #1: all computers are capable of behaving intelligently. Reasonable premise #2: all computers are information processors. Faulty conclusion: all entities that are capable of behaving intelligently are information processors.

Setting aside the formal language, the idea that humans must be information processors just because computers are information processors is just plain silly, and when, some day, the IP metaphor is finally abandoned, it will almost certainly be seen that way by historians, just as we now view the hydraulic and mechanical metaphors to be silly.

If the IP metaphor is so silly, why is it so sticky? What is stopping us from brushing it aside, just as we might brush aside a branch that was blocking our path? Is there a way to understand human intelligence without leaning on a flimsy intellectual crutch? And what price have we paid for leaning so heavily on this particular crutch for so long? The IP metaphor, after all, has been guiding the writing and thinking of a large number of researchers in multiple fields for decades. At what cost?

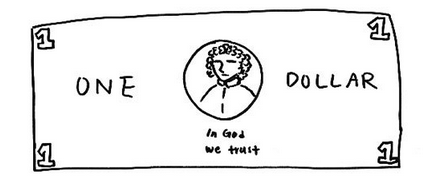

In a classroom exercise I have conducted many times over the years, I begin by recruiting a student to draw a detailed picture of a dollar bill – ‘as detailed as possible’, I say – on the blackboard in front of the room. When the student has finished, I cover the drawing with a sheet of paper, remove a dollar bill from my wallet, tape it to the board, and ask the student to repeat the task. When he or she is done, I remove the cover from the first drawing, and the class comments on the differences.

Because you might never have seen a demonstration like this, or because you might have trouble imagining the outcome, I have asked Jinny Hyun, one of the student interns at the institute where I conduct my research, to make the two drawings. Here is her drawing ‘from memory’ (notice the metaphor):

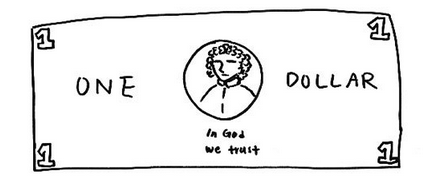

And here is the drawing she subsequently made with a dollar bill present:

Jinny was as surprised by the outcome as you probably are, but it is typical. As you can see, the drawing made in the absence of the dollar bill is horrible compared with the drawing made from an exemplar, even though Jinny has seen a dollar bill thousands of times.

What is the problem? Don’t we have a ‘representation’ of the dollar bill ‘stored’ in a ‘memory register’ in our brains? Can’t we just ‘retrieve’ it and use it to make our drawing?

Obviously not, and a thousand years of neuroscience will never locate a representation of a dollar bill stored inside the human brain for the simple reason that it is not there to be found.

A wealth of brain studies tells us, in fact, that multiple and sometimes large areas of the brain are often involved in even the most mundane memory tasks. When strong emotions are involved, millions of neurons can become more active. In a 2016 study of survivors of a plane crash by the University of Toronto neuropsychologist Brian Levine and others, recalling the crash increased neural activity in ‘the amygdala, medial temporal lobe, anterior and posterior midline, and visual cortex’ of the passengers.

The idea, advanced by several scientists, that specific memories are somehow stored in individual neurons is preposterous; if anything, that assertion just pushes the problem of memory to an even more challenging level: how and where, after all, is the memory stored in the cell?

So what is occurring when Jinny draws the dollar bill in its absence? If Jinny had never seen a dollar bill before, her first drawing would probably have not resembled the second drawing at all. Having seen dollar bills before, she was changed in some way. Specifically, her brain was changed in a way that allowed her to visualise a dollar bill – that is, to re-experience seeing a dollar bill, at least to some extent.

The difference between the two diagrams reminds us that visualising something (that is, seeing something in its absence) is far less accurate than seeing something in its presence. This is why we’re much better at recognising than recalling. When we re-member something (from the Latin re, ‘again’, and memorari, ‘be mindful of’), we have to try to relive an experience; but when we recognise something, we must merely be conscious of the fact that we have had this perceptual experience before.

Perhaps you will object to this demonstration. Jinny had seen dollar bills before, but she hadn’t made a deliberate effort to ‘memorise’ the details. Had she done so, you might argue, she could presumably have drawn the second image without the bill being present. Even in this case, though, no image of the dollar bill has in any sense been ‘stored’ in Jinny’s brain. She has simply become better prepared to draw it accurately, just as, through practice, a pianist becomes more skilled in playing a concerto without somehow inhaling a copy of the sheet music.

From this simple exercise, we can begin to build the framework of a metaphor-free theory of intelligent human behaviour – one in which the brain isn’t completely empty, but is at least empty of the baggage of the IP metaphor.

As we navigate through the world, we are changed by a variety of experiences. Of special note are experiences of three types: (1) we observe what is happening around us (other people behaving, sounds of music, instructions directed at us, words on pages, images on screens); (2) we are exposed to the pairing of unimportant stimuli (such as sirens) with important stimuli (such as the appearance of police cars); (3) we are punished or rewarded for behaving in certain ways.

We become more effective in our lives if we change in ways that are consistent with these experiences – if we can now recite a poem or sing a song, if we are able to follow the instructions we are given, if we respond to the unimportant stimuli more like we do to the important stimuli, if we refrain from behaving in ways that were punished, if we behave more frequently in ways that were rewarded.

Misleading headlines notwithstanding, no one really has the slightest idea how the brain changes after we have learned to sing a song or recite a poem. But neither the song nor the poem has been ‘stored’ in it. The brain has simply changed in an orderly way that now allows us to sing the song or recite the poem under certain conditions. When called on to perform, neither the song nor the poem is in any sense ‘retrieved’ from anywhere in the brain, any more than my finger movements are ‘retrieved’ when I tap my finger on my desk. We simply sing or recite – no retrieval necessary.

A few years ago, I asked the neuroscientist Eric Kandel of Columbia University – winner of a Nobel Prize for identifying some of the chemical changes that take place in the neuronal synapses of the Aplysia (a marine snail) after it learns something – how long he thought it would take us to understand how human memory works. He quickly replied: ‘A hundred years.’ I didn’t think to ask him whether he thought the IP metaphor was slowing down neuroscience, but some neuroscientists are indeed beginning to think the unthinkable – that the metaphor is not indispensable.

A few cognitive scientists – notably Anthony Chemero of the University of Cincinnati, the author of Radical Embodied Cognitive Science (2009) – now completely reject the view that the human brain works like a computer. The mainstream view is that we, like computers, make sense of the world by performing computations on mental representations of it, but Chemero and others describe another way of understanding intelligent behaviour – as a direct interaction between organisms and their world.

My favourite example of the dramatic difference between the IP perspective and what some now call the ‘anti-representational’ view of human functioning involves two different ways of explaining how a baseball player manages to catch a fly ball – beautifully explicated by Michael McBeath, now at Arizona State University, and his colleagues in a 1995 paper in Science. The IP perspective requires the player to formulate an estimate of various initial conditions of the ball’s flight – the force of the impact, the angle of the trajectory, that kind of thing – then to create and analyse an internal model of the path along which the ball will likely move, then to use that model to guide and adjust motor movements continuously in time in order to intercept the ball.

That is all well and good if we functioned as computers do, but McBeath and his colleagues gave a simpler account: to catch the ball, the player simply needs to keep moving in a way that keeps the ball in a constant visual relationship with respect to home plate and the surrounding scenery (technically, in a ‘linear optical trajectory’). This might sound complicated, but it is actually incredibly simple, and completely free of computations, representations and algorithms.

Two determined psychology professors at Leeds Beckett University in the UK – Andrew Wilson and Sabrina Golonka – include the baseball example among many others that can be looked at simply and sensibly outside the IP framework. They have been blogging for years about what they call a ‘more coherent, naturalised approach to the scientific study of human behaviour… at odds with the dominant cognitive neuroscience approach’. This is far from a movement, however; the mainstream cognitive sciences continue to wallow uncritically in the IP metaphor, and some of the world’s most influential thinkers have made grand predictions about humanity’s future that depend on the validity of the metaphor.

One prediction – made by the futurist Kurzweil, the physicist Stephen Hawking and the neuroscientist Randal Koene, among others – is that, because human consciousness is supposedly like computer software, it will soon be possible to download human minds to a computer, in the circuits of which we will become immensely powerful intellectually and, quite possibly, immortal. This concept drove the plot of the dystopian movie Transcendence (2014) starring Johnny Depp as the Kurzweil-like scientist whose mind was downloaded to the internet – with disastrous results for humanity.

Fortunately, because the IP metaphor is not even slightly valid, we will never have to worry about a human mind going amok in cyberspace; alas, we will also never achieve immortality through downloading. This is not only because of the absence of consciousness software in the brain; there is a deeper problem here – let’s call it the uniqueness problem – which is both inspirational and depressing.

Because neither ‘memory banks’ nor ‘representations’ of stimuli exist in the brain, and because all that is required for us to function in the world is for the brain to change in an orderly way as a result of our experiences, there is no reason to believe that any two of us are changed the same way by the same experience. If you and I attend the same concert, the changes that occur in my brain when I listen to Beethoven’s 5th will almost certainly be completely different from the changes that occur in your brain. Those changes, whatever they are, are built on the unique neural structure that already exists, each structure having developed over a lifetime of unique experiences.

This is why, as Sir Frederic Bartlett demonstrated in his book Remembering (1932), no two people will repeat a story they have heard the same way and why, over time, their recitations of the story will diverge more and more. No ‘copy’ of the story is ever made; rather, each individual, upon hearing the story, changes to some extent – enough so that when asked about the story later (in some cases, days, months or even years after Bartlett first read them the story) – they can re-experience hearing the story to some extent, although not very well (see the first drawing of the dollar bill, above).

This is inspirational, I suppose, because it means that each of us is truly unique, not just in our genetic makeup, but even in the way our brains change over time. It is also depressing, because it makes the task of the neuroscientist daunting almost beyond imagination. For any given experience, orderly change could involve a thousand neurons, a million neurons or even the entire brain, with the pattern of change different in every brain.

Worse still, even if we had the ability to take a snapshot of all of the brain’s 86 billion neurons and then to simulate the state of those neurons in a computer, that vast pattern would mean nothing outside the body of the brain that produced it. This is perhaps the most egregious way in which the IP metaphor has distorted our thinking about human functioning. Whereas computers do store exact copies of data – copies that can persist unchanged for long periods of time, even if the power has been turned off – the brain maintains our intellect only as long as it remains alive. There is no on-off switch. Either the brain keeps functioning, or we disappear. What’s more, as the neurobiologist Steven Rose pointed out in The Future of the Brain (2005), a snapshot of the brain’s current state might also be meaningless unless we knew the entire life history of that brain’s owner – perhaps even about the social context in which he or she was raised.

Think how difficult this problem is. To understand even the basics of how the brain maintains the human intellect, we might need to know not just the current state of all 86 billion neurons and their 100 trillion interconnections, not just the varying strengths with which they are connected, and not just the states of more than 1,000 proteins that exist at each connection point, but how the moment-to-moment activity of the brain contributes to the integrity of the system. Add to this the uniqueness of each brain, brought about in part because of the uniqueness of each person’s life history, and Kandel’s prediction starts to sound overly optimistic. (In a recent op-ed in The New York Times, the neuroscientist Kenneth Miller suggested it will take ‘centuries’ just to figure out basic neuronal connectivity.)

Meanwhile, vast sums of money are being raised for brain research, based in some cases on faulty ideas and promises that cannot be kept. The most blatant instance of neuroscience gone awry, documented recently in a report in Scientific American, concerns the $1.3 billion Human Brain Project launched by the European Union in 2013. Convinced by the charismatic Henry Markram that he could create a simulation of the entire human brain on a supercomputer by the year 2023, and that such a model would revolutionise the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders, EU officials funded his project with virtually no restrictions. Less than two years into it, the project turned into a ‘brain wreck’, and Markram was asked to step down.

We are organisms, not computers. Get over it. Let’s get on with the business of trying to understand ourselves, but without being encumbered by unnecessary intellectual baggage. The IP metaphor has had a half-century run, producing few, if any, insights along the way. The time has come to hit the DELETE key.

Robert Epstein is a senior research psychologist at the American Institute for Behavioral Research and Technology in California. He is the author of 15 books, and the former editor-in-chief of Psychology Today.

Archive: https://archive.vn/3JHkH

The Empty Brain

Your brain does not process information, retrieve knowledge, or store memories. In short: Your brain is not a computer.

Aeon Robert EpsteinNo matter how hard they try, brain scientists and cognitive psychologists will never find a copy of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony in the brain – or copies of words, pictures, grammatical rules or any other kinds of environmental stimuli. The human brain isn’t really empty, of course. But it does not contain most of the things people think it does – not even simple things such as ‘memories’.

Our shoddy thinking about the brain has deep historical roots, but the invention of computers in the 1940s got us especially confused. For more than half a century now, psychologists, linguists, neuroscientists and other experts on human behaviour have been asserting that the human brain works like a computer.

To see how vacuous this idea is, consider the brains of babies. Thanks to evolution, human neonates, like the newborns of all other mammalian species, enter the world prepared to interact with it effectively. A baby’s vision is blurry, but it pays special attention to faces, and is quickly able to identify its mother’s. It prefers the sound of voices to non-speech sounds, and can distinguish one basic speech sound from another. We are, without doubt, built to make social connections.

A healthy newborn is also equipped with more than a dozen reflexes – ready-made reactions to certain stimuli that are important for its survival. It turns its head in the direction of something that brushes its cheek and then sucks whatever enters its mouth. It holds its breath when submerged in water. It grasps things placed in its hands so strongly it can nearly support its own weight. Perhaps most important, newborns come equipped with powerful learning mechanisms that allow them to change rapidly so they can interact increasingly effectively with their world, even if that world is unlike the one their distant ancestors faced.

Senses, reflexes and learning mechanisms – this is what we start with, and it is quite a lot, when you think about it. If we lacked any of these capabilities at birth, we would probably have trouble surviving.

But here is what we are not born with: information, data, rules, software, knowledge, lexicons, representations, algorithms, programs, models, memories, images, processors, subroutines, encoders, decoders, symbols, or buffers – design elements that allow digital computers to behave somewhat intelligently. Not only are we not born with such things, we also don’t develop them – ever.

We don’t store words or the rules that tell us how to manipulate them. We don’t create representations of visual stimuli, store them in a short-term memory buffer, and then transfer the representation into a long-term memory device. We don’t retrieve information or images or words from memory registers. Computers do all of these things, but organisms do not.

Computers, quite literally, process information – numbers, letters, words, formulas, images. The information first has to be encoded into a format computers can use, which means patterns of ones and zeroes (‘bits’) organised into small chunks (‘bytes’). On my computer, each byte contains 8 bits, and a certain pattern of those bits stands for the letter d, another for the letter o, and another for the letter g. Side by side, those three bytes form the word dog. One single image – say, the photograph of my cat Henry on my desktop – is represented by a very specific pattern of a million of these bytes (‘one megabyte’), surrounded by some special characters that tell the computer to expect an image, not a word.

Computers, quite literally, move these patterns from place to place in different physical storage areas etched into electronic components. Sometimes they also copy the patterns, and sometimes they transform them in various ways – say, when we are correcting errors in a manuscript or when we are touching up a photograph. The rules computers follow for moving, copying and operating on these arrays of data are also stored inside the computer. Together, a set of rules is called a ‘program’ or an ‘algorithm’. A group of algorithms that work together to help us do something (like buy stocks or find a date online) is called an ‘application’ – what most people now call an ‘app’.

Forgive me for this introduction to computing, but I need to be clear: computers really do operate on symbolic representations of the world. They really store and retrieve. They really process. They really have physical memories. They really are guided in everything they do, without exception, by algorithms.

Humans, on the other hand, do not – never did, never will. Given this reality, why do so many scientists talk about our mental life as if we were computers?

In his book In Our Own Image (2015), the artificial intelligence expert George Zarkadakis describes six different metaphors people have employed over the past 2,000 years to try to explain human intelligence.

In the earliest one, eventually preserved in the Bible, humans were formed from clay or dirt, which an intelligent god then infused with its spirit. That spirit ‘explained’ our intelligence – grammatically, at least.

The invention of hydraulic engineering in the 3rd century BCE led to the popularity of a hydraulic model of human intelligence, the idea that the flow of different fluids in the body – the ‘humours’ – accounted for both our physical and mental functioning. The hydraulic metaphor persisted for more than 1,600 years, handicapping medical practice all the while.

By the 1500s, automata powered by springs and gears had been devised, eventually inspiring leading thinkers such as René Descartes to assert that humans are complex machines. In the 1600s, the British philosopher Thomas Hobbes suggested that thinking arose from small mechanical motions in the brain. By the 1700s, discoveries about electricity and chemistry led to new theories of human intelligence – again, largely metaphorical in nature. In the mid-1800s, inspired by recent advances in communications, the German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz compared the brain to a telegraph.

Each metaphor reflected the most advanced thinking of the era that spawned it. Predictably, just a few years after the dawn of computer technology in the 1940s, the brain was said to operate like a computer, with the role of physical hardware played by the brain itself and our thoughts serving as software. The landmark event that launched what is now broadly called ‘cognitive science’ was the publication of Language and Communication (1951) by the psychologist George Miller. Miller proposed that the mental world could be studied rigorously using concepts from information theory, computation and linguistics.

This kind of thinking was taken to its ultimate expression in the short book The Computer and the Brain (195

Propelled by subsequent advances in both computer technology and brain research, an ambitious multidisciplinary effort to understand human intelligence gradually developed, firmly rooted in the idea that humans are, like computers, information processors. This effort now involves thousands of researchers, consumes billions of dollars in funding, and has generated a vast literature consisting of both technical and mainstream articles and books. Ray Kurzweil’s book How to Create a Mind: The Secret of Human Thought Revealed (2013), exemplifies this perspective, speculating about the ‘algorithms’ of the brain, how the brain ‘processes data’, and even how it superficially resembles integrated circuits in its structure.

The information processing (IP) metaphor of human intelligence now dominates human thinking, both on the street and in the sciences. There is virtually no form of discourse about intelligent human behaviour that proceeds without employing this metaphor, just as no form of discourse about intelligent human behaviour could proceed in certain eras and cultures without reference to a spirit or deity. The validity of the IP metaphor in today’s world is generally assumed without question.

But the IP metaphor is, after all, just another metaphor – a story we tell to make sense of something we don’t actually understand. And like all the metaphors that preceded it, it will certainly be cast aside at some point – either replaced by another metaphor or, in the end, replaced by actual knowledge.

Just over a year ago, on a visit to one of the world’s most prestigious research institutes, I challenged researchers there to account for intelligent human behaviour without reference to any aspect of the IP metaphor. They couldn’t do it, and when I politely raised the issue in subsequent email communications, they still had nothing to offer months later. They saw the problem. They didn’t dismiss the challenge as trivial. But they couldn’t offer an alternative. In other words, the IP metaphor is ‘sticky’. It encumbers our thinking with language and ideas that are so powerful we have trouble thinking around them.

The faulty logic of the IP metaphor is easy enough to state. It is based on a faulty syllogism – one with two reasonable premises and a faulty conclusion. Reasonable premise #1: all computers are capable of behaving intelligently. Reasonable premise #2: all computers are information processors. Faulty conclusion: all entities that are capable of behaving intelligently are information processors.

Setting aside the formal language, the idea that humans must be information processors just because computers are information processors is just plain silly, and when, some day, the IP metaphor is finally abandoned, it will almost certainly be seen that way by historians, just as we now view the hydraulic and mechanical metaphors to be silly.

If the IP metaphor is so silly, why is it so sticky? What is stopping us from brushing it aside, just as we might brush aside a branch that was blocking our path? Is there a way to understand human intelligence without leaning on a flimsy intellectual crutch? And what price have we paid for leaning so heavily on this particular crutch for so long? The IP metaphor, after all, has been guiding the writing and thinking of a large number of researchers in multiple fields for decades. At what cost?

In a classroom exercise I have conducted many times over the years, I begin by recruiting a student to draw a detailed picture of a dollar bill – ‘as detailed as possible’, I say – on the blackboard in front of the room. When the student has finished, I cover the drawing with a sheet of paper, remove a dollar bill from my wallet, tape it to the board, and ask the student to repeat the task. When he or she is done, I remove the cover from the first drawing, and the class comments on the differences.

Because you might never have seen a demonstration like this, or because you might have trouble imagining the outcome, I have asked Jinny Hyun, one of the student interns at the institute where I conduct my research, to make the two drawings. Here is her drawing ‘from memory’ (notice the metaphor):

And here is the drawing she subsequently made with a dollar bill present:

Jinny was as surprised by the outcome as you probably are, but it is typical. As you can see, the drawing made in the absence of the dollar bill is horrible compared with the drawing made from an exemplar, even though Jinny has seen a dollar bill thousands of times.

What is the problem? Don’t we have a ‘representation’ of the dollar bill ‘stored’ in a ‘memory register’ in our brains? Can’t we just ‘retrieve’ it and use it to make our drawing?

Obviously not, and a thousand years of neuroscience will never locate a representation of a dollar bill stored inside the human brain for the simple reason that it is not there to be found.

A wealth of brain studies tells us, in fact, that multiple and sometimes large areas of the brain are often involved in even the most mundane memory tasks. When strong emotions are involved, millions of neurons can become more active. In a 2016 study of survivors of a plane crash by the University of Toronto neuropsychologist Brian Levine and others, recalling the crash increased neural activity in ‘the amygdala, medial temporal lobe, anterior and posterior midline, and visual cortex’ of the passengers.

The idea, advanced by several scientists, that specific memories are somehow stored in individual neurons is preposterous; if anything, that assertion just pushes the problem of memory to an even more challenging level: how and where, after all, is the memory stored in the cell?

So what is occurring when Jinny draws the dollar bill in its absence? If Jinny had never seen a dollar bill before, her first drawing would probably have not resembled the second drawing at all. Having seen dollar bills before, she was changed in some way. Specifically, her brain was changed in a way that allowed her to visualise a dollar bill – that is, to re-experience seeing a dollar bill, at least to some extent.

The difference between the two diagrams reminds us that visualising something (that is, seeing something in its absence) is far less accurate than seeing something in its presence. This is why we’re much better at recognising than recalling. When we re-member something (from the Latin re, ‘again’, and memorari, ‘be mindful of’), we have to try to relive an experience; but when we recognise something, we must merely be conscious of the fact that we have had this perceptual experience before.

Perhaps you will object to this demonstration. Jinny had seen dollar bills before, but she hadn’t made a deliberate effort to ‘memorise’ the details. Had she done so, you might argue, she could presumably have drawn the second image without the bill being present. Even in this case, though, no image of the dollar bill has in any sense been ‘stored’ in Jinny’s brain. She has simply become better prepared to draw it accurately, just as, through practice, a pianist becomes more skilled in playing a concerto without somehow inhaling a copy of the sheet music.

From this simple exercise, we can begin to build the framework of a metaphor-free theory of intelligent human behaviour – one in which the brain isn’t completely empty, but is at least empty of the baggage of the IP metaphor.

As we navigate through the world, we are changed by a variety of experiences. Of special note are experiences of three types: (1) we observe what is happening around us (other people behaving, sounds of music, instructions directed at us, words on pages, images on screens); (2) we are exposed to the pairing of unimportant stimuli (such as sirens) with important stimuli (such as the appearance of police cars); (3) we are punished or rewarded for behaving in certain ways.

We become more effective in our lives if we change in ways that are consistent with these experiences – if we can now recite a poem or sing a song, if we are able to follow the instructions we are given, if we respond to the unimportant stimuli more like we do to the important stimuli, if we refrain from behaving in ways that were punished, if we behave more frequently in ways that were rewarded.

Misleading headlines notwithstanding, no one really has the slightest idea how the brain changes after we have learned to sing a song or recite a poem. But neither the song nor the poem has been ‘stored’ in it. The brain has simply changed in an orderly way that now allows us to sing the song or recite the poem under certain conditions. When called on to perform, neither the song nor the poem is in any sense ‘retrieved’ from anywhere in the brain, any more than my finger movements are ‘retrieved’ when I tap my finger on my desk. We simply sing or recite – no retrieval necessary.

A few years ago, I asked the neuroscientist Eric Kandel of Columbia University – winner of a Nobel Prize for identifying some of the chemical changes that take place in the neuronal synapses of the Aplysia (a marine snail) after it learns something – how long he thought it would take us to understand how human memory works. He quickly replied: ‘A hundred years.’ I didn’t think to ask him whether he thought the IP metaphor was slowing down neuroscience, but some neuroscientists are indeed beginning to think the unthinkable – that the metaphor is not indispensable.

A few cognitive scientists – notably Anthony Chemero of the University of Cincinnati, the author of Radical Embodied Cognitive Science (2009) – now completely reject the view that the human brain works like a computer. The mainstream view is that we, like computers, make sense of the world by performing computations on mental representations of it, but Chemero and others describe another way of understanding intelligent behaviour – as a direct interaction between organisms and their world.

My favourite example of the dramatic difference between the IP perspective and what some now call the ‘anti-representational’ view of human functioning involves two different ways of explaining how a baseball player manages to catch a fly ball – beautifully explicated by Michael McBeath, now at Arizona State University, and his colleagues in a 1995 paper in Science. The IP perspective requires the player to formulate an estimate of various initial conditions of the ball’s flight – the force of the impact, the angle of the trajectory, that kind of thing – then to create and analyse an internal model of the path along which the ball will likely move, then to use that model to guide and adjust motor movements continuously in time in order to intercept the ball.

That is all well and good if we functioned as computers do, but McBeath and his colleagues gave a simpler account: to catch the ball, the player simply needs to keep moving in a way that keeps the ball in a constant visual relationship with respect to home plate and the surrounding scenery (technically, in a ‘linear optical trajectory’). This might sound complicated, but it is actually incredibly simple, and completely free of computations, representations and algorithms.

Two determined psychology professors at Leeds Beckett University in the UK – Andrew Wilson and Sabrina Golonka – include the baseball example among many others that can be looked at simply and sensibly outside the IP framework. They have been blogging for years about what they call a ‘more coherent, naturalised approach to the scientific study of human behaviour… at odds with the dominant cognitive neuroscience approach’. This is far from a movement, however; the mainstream cognitive sciences continue to wallow uncritically in the IP metaphor, and some of the world’s most influential thinkers have made grand predictions about humanity’s future that depend on the validity of the metaphor.

One prediction – made by the futurist Kurzweil, the physicist Stephen Hawking and the neuroscientist Randal Koene, among others – is that, because human consciousness is supposedly like computer software, it will soon be possible to download human minds to a computer, in the circuits of which we will become immensely powerful intellectually and, quite possibly, immortal. This concept drove the plot of the dystopian movie Transcendence (2014) starring Johnny Depp as the Kurzweil-like scientist whose mind was downloaded to the internet – with disastrous results for humanity.

Fortunately, because the IP metaphor is not even slightly valid, we will never have to worry about a human mind going amok in cyberspace; alas, we will also never achieve immortality through downloading. This is not only because of the absence of consciousness software in the brain; there is a deeper problem here – let’s call it the uniqueness problem – which is both inspirational and depressing.

Because neither ‘memory banks’ nor ‘representations’ of stimuli exist in the brain, and because all that is required for us to function in the world is for the brain to change in an orderly way as a result of our experiences, there is no reason to believe that any two of us are changed the same way by the same experience. If you and I attend the same concert, the changes that occur in my brain when I listen to Beethoven’s 5th will almost certainly be completely different from the changes that occur in your brain. Those changes, whatever they are, are built on the unique neural structure that already exists, each structure having developed over a lifetime of unique experiences.

This is why, as Sir Frederic Bartlett demonstrated in his book Remembering (1932), no two people will repeat a story they have heard the same way and why, over time, their recitations of the story will diverge more and more. No ‘copy’ of the story is ever made; rather, each individual, upon hearing the story, changes to some extent – enough so that when asked about the story later (in some cases, days, months or even years after Bartlett first read them the story) – they can re-experience hearing the story to some extent, although not very well (see the first drawing of the dollar bill, above).

This is inspirational, I suppose, because it means that each of us is truly unique, not just in our genetic makeup, but even in the way our brains change over time. It is also depressing, because it makes the task of the neuroscientist daunting almost beyond imagination. For any given experience, orderly change could involve a thousand neurons, a million neurons or even the entire brain, with the pattern of change different in every brain.

Worse still, even if we had the ability to take a snapshot of all of the brain’s 86 billion neurons and then to simulate the state of those neurons in a computer, that vast pattern would mean nothing outside the body of the brain that produced it. This is perhaps the most egregious way in which the IP metaphor has distorted our thinking about human functioning. Whereas computers do store exact copies of data – copies that can persist unchanged for long periods of time, even if the power has been turned off – the brain maintains our intellect only as long as it remains alive. There is no on-off switch. Either the brain keeps functioning, or we disappear. What’s more, as the neurobiologist Steven Rose pointed out in The Future of the Brain (2005), a snapshot of the brain’s current state might also be meaningless unless we knew the entire life history of that brain’s owner – perhaps even about the social context in which he or she was raised.

Think how difficult this problem is. To understand even the basics of how the brain maintains the human intellect, we might need to know not just the current state of all 86 billion neurons and their 100 trillion interconnections, not just the varying strengths with which they are connected, and not just the states of more than 1,000 proteins that exist at each connection point, but how the moment-to-moment activity of the brain contributes to the integrity of the system. Add to this the uniqueness of each brain, brought about in part because of the uniqueness of each person’s life history, and Kandel’s prediction starts to sound overly optimistic. (In a recent op-ed in The New York Times, the neuroscientist Kenneth Miller suggested it will take ‘centuries’ just to figure out basic neuronal connectivity.)

Meanwhile, vast sums of money are being raised for brain research, based in some cases on faulty ideas and promises that cannot be kept. The most blatant instance of neuroscience gone awry, documented recently in a report in Scientific American, concerns the $1.3 billion Human Brain Project launched by the European Union in 2013. Convinced by the charismatic Henry Markram that he could create a simulation of the entire human brain on a supercomputer by the year 2023, and that such a model would revolutionise the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders, EU officials funded his project with virtually no restrictions. Less than two years into it, the project turned into a ‘brain wreck’, and Markram was asked to step down.

We are organisms, not computers. Get over it. Let’s get on with the business of trying to understand ourselves, but without being encumbered by unnecessary intellectual baggage. The IP metaphor has had a half-century run, producing few, if any, insights along the way. The time has come to hit the DELETE key.

Robert Epstein is a senior research psychologist at the American Institute for Behavioral Research and Technology in California. He is the author of 15 books, and the former editor-in-chief of Psychology Today.