L | A

By Henry Samuel and Flora Bowen

Few would deny that English has conquered the world.

But the French have always refused to take this linguistic victory lying down.

For centuries, the “immortal” guardians of the French language at the Académie Française, France’s linguistic authority since 1634, have arguably been fighting a losing battle to contain the invasion of anglais.

Theirs is a Sisyphean task as they toil in coming up with French alternatives to English words such as “gazoduc” instead of pipeline, or the more recent “icône de la mode” instead of “it girl”, in the hope they will catch on.

Now, however, a new book has challenged claims of English dominance with a beautifully simple premise which may risk putting the Académiciens out of a job.

The English language doesn’t exist. It’s just badly pronounced French is the title of a new treatise, published in France this week by French linguist Bernard Cerquiglini.

It is no secret that “English is spoken (as a first or second language) by more than a billion human beings,” he concedes. And yet “the real power of English and its universal prestige, its value, its ability to deal with everything, is due to the massive use of one particular language: French.”

“The French language has provided English with its colour and originality”, his argument continues, “an abstract vocabulary, the lexicon of commerce and administration, its legal and political terms, etc. Everything that has made it a sought-after, used and esteemed international language.

“We will not shy away from asserting that English owes its worldwide influence to French; we will maintain that it is French that shines through English.”

A touch provocative? “Évidemment, I make no bones about that,” he says. “This is a book written in bad faith. It’s a French book. So (it is) arrogant.”

Thus the global rise of English is nothing more than “a tribute to the French-speaking world, the payment of an age-old debt to our language.”

Touché.

Cerquiglini is no mere pamphleteer (another word pilfered from French). He has spent his career in the front line of the language wars, defending his native tongue as former director of the National Institute for the French Language, and as former vice-president of the Higher Council of the French Language. He has even written an “Autobiography of the Circumflex”, on the accent mark used in words such as ‘hôpital’).

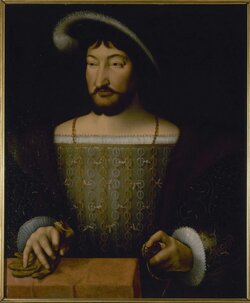

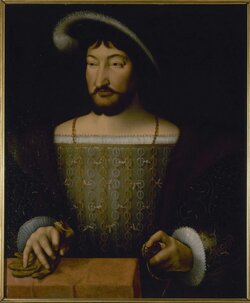

More recently he has advised President Emmanuel Macron on his development of The Cité internationale de la langue française, a €211 million temple to French language and culture, launched late last year in Villers-Cotterêts château 50 miles north of Paris, where in 1539 King François I signed an edict adopting French as his nation’s official tongue.

President Emmanuel Macron has been developing a €211 million temple to French language and culture, the Cité internationale de la langue française

According to Cerquiglini’s research, more than 80,000 terms – a third of the English vocabulary – are of French origin, the equivalent of an entire lesser Le Petit Larousse French dictionary. Including Latin, this surpasses 50 per cent.

Some 40 per cent of the 15,000 words in Shakespeare’s works were of French origin. The same percentage can be found in the current English version of the Bible.

“English, full of French, Norman and Latin, is more of a Romance language than a Germanic one,” writes Cerquiglini. “Its Saxon backbone is clothed in a luxuriant and precious Roman flesh.”

Such revelations may come as a surprise to Anglophone speakers.

Widespread ignorance of English’s French ancestry may be summed up by George W Bush’s notorious alleged complaint that, “The trouble with the French is that they have no word for entrepreneur.”

Indeed, the only inkling many Brits have that French may play a significant role in their language is when reading the words “Dieu et mon droit” and “Honi soit qui mal y pense” on the royal coat of arms of their passports.

Portrait of King Francois I of France, who in 1539 signed an edict adopting French as the nation's official tongue

Take the English breakfast.

The word “bacon” comes from Old French, meaning ham. Mushroom, known today as “champignon” in French, actually comes from the old Norman word “mousheron”. Toast, meanwhile, comes from the old French “tostée”.

Porridge comes from “pottage”, meaning “food cooked in a pot” and roast beef comes from the French “rosbif”, a mixture of the medieval French verb rostir and the “buef”.

In sport, the French coined tennis, penalty and squash, he insists.

Vintage comes from “vendanges” meaning wine harvest, “cottage” from the old Norman “cotage” meaning rustic little home. Gin, that most British of drinks, comes from old French genevre (juniper). ‘Tonic’ is Gallic.

Perhaps more logically, the term “sex shop” is of Gallic origin – a cross between the French and Latin word “sexe” and old French “eschoppe”, which mixes with the Dutch word schoppe. “Should we be proud?,” he asks.

If you insult a Frenchman with the words bastard, brute, coward, cretin, idiot, imbecile, rascal, poltroon, scoundrel and stupid, you are essentially using his own lingo against him.

Coward, for example, comes from the old French term “coard” derived from “coe” (tail), suggesting someone with “their tail between their legs”.

Naturally, the rot started in 1066. After the Norman conquest and ensuing colonisation, French became the language of the ruling class. “The Anglo-Saxon people and their language were under the yoke” for two centuries, until a descendant of William could muster enough English to address Parliament.

Germanic words were used for livestock tended by the poor like oxen, sheep and swine or pigs, while noble French words used for the same animals on plates: beef, mutton and pork.

As Cerquiglini puts it, “Without the Normans, English would be a second Dutch language today.”

Words of Saxon origin are concrete and linked to experience, while those of French origin are more “abstract and intellectual”, he says, comparing, say, “to ask” (Saxon) and “to demand” (French).

In addition, English incorporates Latin as a noble third means of expression, giving rise to “weary” (Saxon), “fatigued” (French), and “exhausted” (Latin).

Even the grammar and syntax of English can be traced to our cross-Channel neighbours. “The word order of 14th-century English, for example, is closer to French than to Old English: just look at Geoffrey Chaucer (14th century) and Beowulf (7th century) side by side.”

While French ceased to be a mother tongue after the Hundred Years War, it maintained status as a second language in education, commerce and law.

In that time, it took on a new life and became what he calls “insular French”, turning English into a “museum” of Old French expressions and giving rise to many “faux amis” (false friends), expressions that exist on both sides of the Channel but mean subtly different things.

For example “cave”, from the Old French word “cave” (meaning cavern) kept its Medieval meaning in English, but morphed to cellar in modern French.

French as an official and common language slowly lost its uses and privileges from the 15th century until the end of the 16th, when English came into universal usage. However, French, he says, remained Europe’s most prestigious language and continued to heavily influence English until the 19th century.

Dr Christophe Gagne, a Fellow in French at the University of Cambridge, says the thesis is “provocative” but “valid”. However, English has also significantly influenced French vocabulary, he argues.

“There has always been this kind of cultural exchange going on, as the two countries are so close. Sometimes it is not at all obvious to French or English speakers which words come first.”

“It is true that French significantly influenced the English lexicon in the mediaeval period, but from the 19th century onwards, we see the English influence in French more, with Anglomanie and then later on in the 20th and 21st century with sport, and technology.

“I noticed it in the 2000s, when I was working as a translator. Anglicisms like digitale and computer were becoming very common in French, but they were certainly frowned upon.”

France’s equivalent of the Commonwealth, “la francophonie” (which unites France with its former colonies) is the only international political organisation based on a language.

“The problem is that intervention is a French tradition. We’ve been interfering with language since time immemorial, and it’s what the French expect,” says Cerquiglini.

“The Académie Française has a ridiculous uniform, granted, but it’s a state institution with a unique status and receives bags of mail every day from people imploring it to act against bad spelling and creeping English.

“Our ties are above all through the French language, it’s what unites us politically.”

In 2022, the Académie published a doom-laden report warning that the invasion of “franglais” in public life risked fuelling social unrest. “We are at a crossroads. There will come a time when things become irreversible,” warned its late president Hélène Carrère d’Encausse.

For the first time in almost five centuries, it threatened to take the government to France’s supreme administrative court unless it removed English words like “surname” from the country’s new biometric identity cards.

A French court recently ordered an airport in eastern France to change its name from Lorraine Airport to Lorraine Aéroport after complaints it infringed laws on using English and was an insulting example of “anglo-mania”.

Even Macron has been slated for speaking franglais – with language purists criticising the President for peppering his speech with too many Anglicisms.

Rather than taking such a defensive position against English, says Gagne, this linguistic mélange can open up the benefits of English culture to the French.

“This process obviously does happen, and it is very natural. You can’t stop English words from being borrowed and assimilated into the language.”

On a personal and professional level, he says, speaking English has allowed him to enjoy the benefits of English culture.

“It is hard to separate English from English speakers. Politeness and a sense of being indirect seems to be very closely linked to English, I have found. It seems to me that the language works well with understatement, and euphemism, and developing humour through this, which is nice. There is a softness in English, especially British English, that you don’t find in French.

“The ability to make puns, as well as more subtle humour, is a fascinating part of the English language. Although I will add that in medical affairs, I would prefer to have a French doctor who can just say what is wrong with you directly.”

Cerquiglini, too, offers praise for English as a language of assimilation. “English has no problem adopting foreign words, whether they be Chinese or Viking. It’s flexible. French has a harder time of it because it has always been a state language where a foreign word is almost viewed as the enemy.”

That said, Cerquiglini has no problem with anglicisms if well-used. “Purists who denounce an Anglo-Saxon lexical invasion are mistaken. From our perspective, the current anglicisation is an internal mutation of the French language: anglicisms are neologisms of French.”

However, he draws the line at dumbed-down “globish”.

“Global English is deliberately basic, utilitarian jargon with impoverished syntax and a minimal lexicon. In this unfortunate “desperanto”, French speakers recognise nothing of their language; they have every reason to refuse to use it,” he sniffs.

But it is as much a problem for Britain as France, he warns.

“It’s bad for French but it’s bad for English whose richness is disappearing. It’s an impoverishment.”

On the 120th anniversary year of Entente Cordiale, he suggests that King Charles set up a “British Academy” on the Académie Française blueprint to “defend British English”.

“I know that Charles is worried about the impoverishment of international English. Paradoxically, we have to defend each other.”

Above all, he says, he hopes mother-tongue English-speakers will not take offence at his claims.

“I really mean to say the French have helped enrich English and say so using British-style humour with a stiff upper lip. I hope I have succeeded.”

By Henry Samuel and Flora Bowen

Few would deny that English has conquered the world.

But the French have always refused to take this linguistic victory lying down.

For centuries, the “immortal” guardians of the French language at the Académie Française, France’s linguistic authority since 1634, have arguably been fighting a losing battle to contain the invasion of anglais.

Theirs is a Sisyphean task as they toil in coming up with French alternatives to English words such as “gazoduc” instead of pipeline, or the more recent “icône de la mode” instead of “it girl”, in the hope they will catch on.

Now, however, a new book has challenged claims of English dominance with a beautifully simple premise which may risk putting the Académiciens out of a job.

The English language doesn’t exist. It’s just badly pronounced French is the title of a new treatise, published in France this week by French linguist Bernard Cerquiglini.

It is no secret that “English is spoken (as a first or second language) by more than a billion human beings,” he concedes. And yet “the real power of English and its universal prestige, its value, its ability to deal with everything, is due to the massive use of one particular language: French.”

“The French language has provided English with its colour and originality”, his argument continues, “an abstract vocabulary, the lexicon of commerce and administration, its legal and political terms, etc. Everything that has made it a sought-after, used and esteemed international language.

“We will not shy away from asserting that English owes its worldwide influence to French; we will maintain that it is French that shines through English.”

A touch provocative? “Évidemment, I make no bones about that,” he says. “This is a book written in bad faith. It’s a French book. So (it is) arrogant.”

Thus the global rise of English is nothing more than “a tribute to the French-speaking world, the payment of an age-old debt to our language.”

Touché.

Cerquiglini is no mere pamphleteer (another word pilfered from French). He has spent his career in the front line of the language wars, defending his native tongue as former director of the National Institute for the French Language, and as former vice-president of the Higher Council of the French Language. He has even written an “Autobiography of the Circumflex”, on the accent mark used in words such as ‘hôpital’).

More recently he has advised President Emmanuel Macron on his development of The Cité internationale de la langue française, a €211 million temple to French language and culture, launched late last year in Villers-Cotterêts château 50 miles north of Paris, where in 1539 King François I signed an edict adopting French as his nation’s official tongue.

President Emmanuel Macron has been developing a €211 million temple to French language and culture, the Cité internationale de la langue française

According to Cerquiglini’s research, more than 80,000 terms – a third of the English vocabulary – are of French origin, the equivalent of an entire lesser Le Petit Larousse French dictionary. Including Latin, this surpasses 50 per cent.

Some 40 per cent of the 15,000 words in Shakespeare’s works were of French origin. The same percentage can be found in the current English version of the Bible.

“English, full of French, Norman and Latin, is more of a Romance language than a Germanic one,” writes Cerquiglini. “Its Saxon backbone is clothed in a luxuriant and precious Roman flesh.”

Such revelations may come as a surprise to Anglophone speakers.

Widespread ignorance of English’s French ancestry may be summed up by George W Bush’s notorious alleged complaint that, “The trouble with the French is that they have no word for entrepreneur.”

Indeed, the only inkling many Brits have that French may play a significant role in their language is when reading the words “Dieu et mon droit” and “Honi soit qui mal y pense” on the royal coat of arms of their passports.

Portrait of King Francois I of France, who in 1539 signed an edict adopting French as the nation's official tongue

Key coinages

Cerquiglini delights in showing how apparently quintessentially British vocabulary is in fact French.Take the English breakfast.

The word “bacon” comes from Old French, meaning ham. Mushroom, known today as “champignon” in French, actually comes from the old Norman word “mousheron”. Toast, meanwhile, comes from the old French “tostée”.

Porridge comes from “pottage”, meaning “food cooked in a pot” and roast beef comes from the French “rosbif”, a mixture of the medieval French verb rostir and the “buef”.

In sport, the French coined tennis, penalty and squash, he insists.

Vintage comes from “vendanges” meaning wine harvest, “cottage” from the old Norman “cotage” meaning rustic little home. Gin, that most British of drinks, comes from old French genevre (juniper). ‘Tonic’ is Gallic.

Perhaps more logically, the term “sex shop” is of Gallic origin – a cross between the French and Latin word “sexe” and old French “eschoppe”, which mixes with the Dutch word schoppe. “Should we be proud?,” he asks.

If you insult a Frenchman with the words bastard, brute, coward, cretin, idiot, imbecile, rascal, poltroon, scoundrel and stupid, you are essentially using his own lingo against him.

Coward, for example, comes from the old French term “coard” derived from “coe” (tail), suggesting someone with “their tail between their legs”.

A complex relationship

The influence of French over English reflects the varied and complex relationship between the two countries.Naturally, the rot started in 1066. After the Norman conquest and ensuing colonisation, French became the language of the ruling class. “The Anglo-Saxon people and their language were under the yoke” for two centuries, until a descendant of William could muster enough English to address Parliament.

Germanic words were used for livestock tended by the poor like oxen, sheep and swine or pigs, while noble French words used for the same animals on plates: beef, mutton and pork.

As Cerquiglini puts it, “Without the Normans, English would be a second Dutch language today.”

Words of Saxon origin are concrete and linked to experience, while those of French origin are more “abstract and intellectual”, he says, comparing, say, “to ask” (Saxon) and “to demand” (French).

In addition, English incorporates Latin as a noble third means of expression, giving rise to “weary” (Saxon), “fatigued” (French), and “exhausted” (Latin).

Even the grammar and syntax of English can be traced to our cross-Channel neighbours. “The word order of 14th-century English, for example, is closer to French than to Old English: just look at Geoffrey Chaucer (14th century) and Beowulf (7th century) side by side.”

While French ceased to be a mother tongue after the Hundred Years War, it maintained status as a second language in education, commerce and law.

In that time, it took on a new life and became what he calls “insular French”, turning English into a “museum” of Old French expressions and giving rise to many “faux amis” (false friends), expressions that exist on both sides of the Channel but mean subtly different things.

For example “cave”, from the Old French word “cave” (meaning cavern) kept its Medieval meaning in English, but morphed to cellar in modern French.

French as an official and common language slowly lost its uses and privileges from the 15th century until the end of the 16th, when English came into universal usage. However, French, he says, remained Europe’s most prestigious language and continued to heavily influence English until the 19th century.

Dr Christophe Gagne, a Fellow in French at the University of Cambridge, says the thesis is “provocative” but “valid”. However, English has also significantly influenced French vocabulary, he argues.

“There has always been this kind of cultural exchange going on, as the two countries are so close. Sometimes it is not at all obvious to French or English speakers which words come first.”

“It is true that French significantly influenced the English lexicon in the mediaeval period, but from the 19th century onwards, we see the English influence in French more, with Anglomanie and then later on in the 20th and 21st century with sport, and technology.

“I noticed it in the 2000s, when I was working as a translator. Anglicisms like digitale and computer were becoming very common in French, but they were certainly frowned upon.”

Franglais

Preventing the creeping Anglicisation of French has been a particular obsession of the Académie Francaise since its inception.France’s equivalent of the Commonwealth, “la francophonie” (which unites France with its former colonies) is the only international political organisation based on a language.

“The problem is that intervention is a French tradition. We’ve been interfering with language since time immemorial, and it’s what the French expect,” says Cerquiglini.

“The Académie Française has a ridiculous uniform, granted, but it’s a state institution with a unique status and receives bags of mail every day from people imploring it to act against bad spelling and creeping English.

“Our ties are above all through the French language, it’s what unites us politically.”

In 2022, the Académie published a doom-laden report warning that the invasion of “franglais” in public life risked fuelling social unrest. “We are at a crossroads. There will come a time when things become irreversible,” warned its late president Hélène Carrère d’Encausse.

For the first time in almost five centuries, it threatened to take the government to France’s supreme administrative court unless it removed English words like “surname” from the country’s new biometric identity cards.

A French court recently ordered an airport in eastern France to change its name from Lorraine Airport to Lorraine Aéroport after complaints it infringed laws on using English and was an insulting example of “anglo-mania”.

Even Macron has been slated for speaking franglais – with language purists criticising the President for peppering his speech with too many Anglicisms.

Rather than taking such a defensive position against English, says Gagne, this linguistic mélange can open up the benefits of English culture to the French.

“This process obviously does happen, and it is very natural. You can’t stop English words from being borrowed and assimilated into the language.”

On a personal and professional level, he says, speaking English has allowed him to enjoy the benefits of English culture.

“It is hard to separate English from English speakers. Politeness and a sense of being indirect seems to be very closely linked to English, I have found. It seems to me that the language works well with understatement, and euphemism, and developing humour through this, which is nice. There is a softness in English, especially British English, that you don’t find in French.

“The ability to make puns, as well as more subtle humour, is a fascinating part of the English language. Although I will add that in medical affairs, I would prefer to have a French doctor who can just say what is wrong with you directly.”

Cerquiglini, too, offers praise for English as a language of assimilation. “English has no problem adopting foreign words, whether they be Chinese or Viking. It’s flexible. French has a harder time of it because it has always been a state language where a foreign word is almost viewed as the enemy.”

That said, Cerquiglini has no problem with anglicisms if well-used. “Purists who denounce an Anglo-Saxon lexical invasion are mistaken. From our perspective, the current anglicisation is an internal mutation of the French language: anglicisms are neologisms of French.”

However, he draws the line at dumbed-down “globish”.

“Global English is deliberately basic, utilitarian jargon with impoverished syntax and a minimal lexicon. In this unfortunate “desperanto”, French speakers recognise nothing of their language; they have every reason to refuse to use it,” he sniffs.

But it is as much a problem for Britain as France, he warns.

“It’s bad for French but it’s bad for English whose richness is disappearing. It’s an impoverishment.”

On the 120th anniversary year of Entente Cordiale, he suggests that King Charles set up a “British Academy” on the Académie Française blueprint to “defend British English”.

“I know that Charles is worried about the impoverishment of international English. Paradoxically, we have to defend each other.”

Above all, he says, he hopes mother-tongue English-speakers will not take offence at his claims.

“I really mean to say the French have helped enrich English and say so using British-style humour with a stiff upper lip. I hope I have succeeded.”