The Law of Averages

April 15, 2024

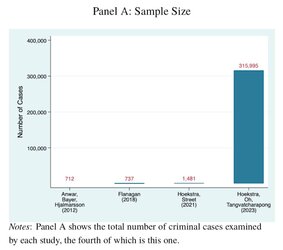

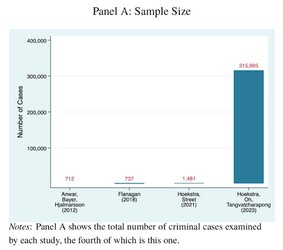

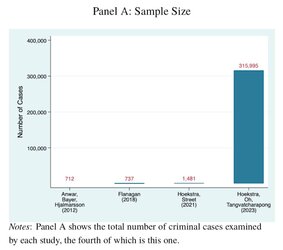

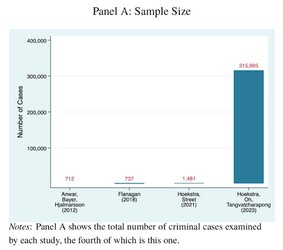

A study published in the National Bureau of Economic Research on October 30th, 2023, and presented at 2 NBER research conferences [here and here] (one on law and economics, and another on crime) titled “Are American juries racially discriminatory? Evidence from over a quarter million felony grand jury cases” is the largest jury study to ever be done, analyzing 300,000+ felony cases over a 3+ decade period, to test if juries are racially discriminatory.

The conclusion?

Their dataset included “every grand jury case filed from February of 1990 through July of 2022“ in the state of Texas, making it the largest study on jurors ever! (And it isn’t even close)

If Black defendants who are falsely thought to be White have it easier, that’d be evidence of anti-Black bias. If Black defendants who are falsely thought to be White have it the same, that’d be evidence against anti-Black bias. If Black defendants who are falsely thought to be White have it harder, that’d be evidence of pro-Black bias.

There were 3 possible results: direct discrimination, indirect discrimination, or no discrimination.

The researchers found that the “small but statistically significant” racial disparity that did exist between Whites and Blacks was no less when Blacks were not known to be Black compared to when Blacks were–no discrimination.

In fact, there wasn’t just no anti-Black bias, but there was anti-White bias found. Specifically, when a Black defendant was thought to be White by jurors, they were more likely to have their cases pushed forward than if a Black defendant was thought to be Black, to a larger extent than the original Black-White disparity between known races.

The authors solved one disparity but accidentally stumbled upon another.

The Black-White disparity was a result of differences in the cases of Black and White defendants, rather than any sort of racial discrimination.

The conclusion of ‘no discrimination’ was supported by the similarities between the proportion of both Black defendant groups among the felony categories.

There is one quote in which they basically summarize everything that matters (albeit it is mostly a repeat of what we went over above):

The authors conclude that Americans do not discriminate based on race when in the position of a grand jury.

P.S. I think this conclusion is a little disingenuous since they attributed discrimination as a possible explanation for the anti-Black gap between Blacks and Whites, but not for the even larger anti-White gap between Blacks with White names and Blacks with Black names. To me, it appears that while the Black-White gap is entirely due to case differences, it also seems as though jurors discriminate against Whiter names, all else equal–as we can see when they compare Blacks with different racially identifiable names.

Source (Archive)

April 15, 2024

A study published in the National Bureau of Economic Research on October 30th, 2023, and presented at 2 NBER research conferences [here and here] (one on law and economics, and another on crime) titled “Are American juries racially discriminatory? Evidence from over a quarter million felony grand jury cases” is the largest jury study to ever be done, analyzing 300,000+ felony cases over a 3+ decade period, to test if juries are racially discriminatory.

The conclusion?

“[G]rand jurors do not engage in statistical or taste-based discrimination against Black defendants.”

Their dataset included “every grand jury case filed from February of 1990 through July of 2022“ in the state of Texas, making it the largest study on jurors ever! (And it isn’t even close)

What they did to test for discrimination was see if racial disparity goes away when comparing Black defendants whose race is accurately identified to Black defendants whose race is inaccurately identified (as White).“the setting of grand juries enables us to test whether a representative set of U.S. citizens engages in racial bias using a data set of cases that is vastly larger than any previous jury data set.“

If Black defendants who are falsely thought to be White have it easier, that’d be evidence of anti-Black bias. If Black defendants who are falsely thought to be White have it the same, that’d be evidence against anti-Black bias. If Black defendants who are falsely thought to be White have it harder, that’d be evidence of pro-Black bias.

“because grand juries do not directly observe the race of the defendant, we can provide estimates for cases that are unblinded (i.e., race can be easily inferred based on first and last name, which are observed), as well as for cases that are blinded (i.e., comparing White defendants to Black defendants with White names). This enables us to perform a simple, intuitive test of whether any disparate impact is due to…discrimination”

There were 3 possible results: direct discrimination, indirect discrimination, or no discrimination.

“we capture the sum of taste-based bias, statistical discrimination, and non-race-based disparate impact.”

“taste-based racial bias or statistical discrimination—both of which are illegal—or if it is due to similar treatment on the basis of something correlated with race“

“equal treatment on the basis of some other factor that differs across race—such as having a lower threshold of guilt for some types of cases, which may be more common among Black defendants“

The researchers found that the “small but statistically significant” racial disparity that did exist between Whites and Blacks was no less when Blacks were not known to be Black compared to when Blacks were–no discrimination.

“there is similar disparate impact against Black defendants even when race is unobserved by the grand jurors. “

“None of the estimates is positive, and thus none suggests the presents of taste-based racial bias or statistical discrimination against identifiably-Black defendants. Rather, estimates in Columns (2) and (3) are close to zero and statistically insignificant.

In fact, there wasn’t just no anti-Black bias, but there was anti-White bias found. Specifically, when a Black defendant was thought to be White by jurors, they were more likely to have their cases pushed forward than if a Black defendant was thought to be Black, to a larger extent than the original Black-White disparity between known races.

“if anything disparate impact estimates against Black defendants who are likely inferred as White are slightly larger, which is the opposite of what we would expect if some or all of the disparate impact…were due to taste-based or statistical discrimination based on race.”

“The estimate…is negative and significant, and is thus the opposite of what one would expect in the presence of taste-based or statistical discrimination based on race against Black defendants.“

“Figure 2 also shows, consistent with Tables 3 and 4, that the disparate impact estimates for Black defendants with White names is slightly higher than those for Black defendants with Black names, which is the opposite of what we would expect in the presence of taste-based or statistical discrimination based on race.“

The authors solved one disparity but accidentally stumbled upon another.

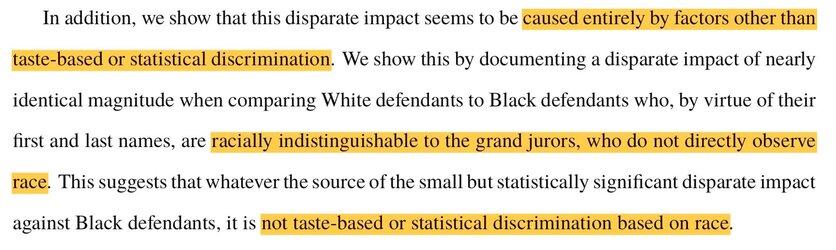

The Black-White disparity was a result of differences in the cases of Black and White defendants, rather than any sort of racial discrimination.

“we show that this disparate impact seems to be caused entirely by factors other than taste-based or statistical discrimination. We show this by documenting a disparate impact of nearly identical magnitude when comparing White defendants to Black defendants who, by virtue of their first and last names, are racially indistinguishable to the grand jurors, who do not directly observe race.“

“In summary, results in Table 5 indicate that grand jurors do not engage in statistical or taste-based discrimination against Black defendants. Rather, the small but statistically significant 0.8 percent disparate impact…appears to be due to jurors applying a slightly lower threshold for guilt to cases that tend to be slightly more common among Black defendants, compared to White ones.“

“whatever the cause of the disparate impact against identifiably-Black defendants…it is unlikely to be taste-based racial bias or statistical discrimination.”

“whatever is driving the disparate impact, it does not seem to be either racial bias or statistical discrimination.”

“whatever the source of the small but statistically significant disparate impact against Black defendants, it is not taste-based or statistical discrimination based on race.”

The conclusion of ‘no discrimination’ was supported by the similarities between the proportion of both Black defendant groups among the felony categories.

“our approach to distinguishing between statistical or taste-based bias from other non-race-based behaviors that have disparate impact, as our approach assumes that the latter would be similar across the two groups of Black defendants…this is a reasonable assumption, as the cases of both groups of Black defendants are similar to each other, and different from those of identifiably-White defendants.”

“Of cases with identifiably-Black (identifiably-White) defendants, 12.6 (12.7), 22.6 (22., and 26.9 (27.1) percent are 1st, 2nd, and 3rd degree felonies, respectively. “

Gaps of 0.1 0.2 0.2

There is one quote in which they basically summarize everything that matters (albeit it is mostly a repeat of what we went over above):

“Strikingly, results indicate a similar, if not slightly larger, disparate impact when comparing Black and White defendants who had similarly-White names, and were thus racially indistinguishable to grand jurors. That is, compared to racially-identifiable White defendants, Black defendants who were likely believed to be White by grand jurors were 0.9 percent more likely to have their felony cases pushed forward. The similarity of findings across the “unblinded” and “blinded” samples indicates that the disparate impact estimated between White and Black defendants is not caused by either taste-based or statistical discrimination, but rather is due to similar treatment on the basis of some other factor that differs across race“

The authors conclude that Americans do not discriminate based on race when in the position of a grand jury.

“These results have important implications…in the context of grand juries, U.S. citizens do not seem to engage in taste-based or statistical discrimination based on race…our finding of relatively modest disparate impact of less than one percent casts some doubt that the large racial disparities observed in felony charging and convictions are due to unwarranted disparate impact.“

P.S. I think this conclusion is a little disingenuous since they attributed discrimination as a possible explanation for the anti-Black gap between Blacks and Whites, but not for the even larger anti-White gap between Blacks with White names and Blacks with Black names. To me, it appears that while the Black-White gap is entirely due to case differences, it also seems as though jurors discriminate against Whiter names, all else equal–as we can see when they compare Blacks with different racially identifiable names.

Source (Archive)