Trump Slashed International Aid. Geneva Is Feeling the Impact.

Bloomberg (archive.ph)

By Hugo Miller

2025-03-25 05:00:21GMT

Geneva boasts 38 international organizations that employ 29,000 people, spend some $7 billion each year and support around 400 NGOs — all of which are now facing funding challenges.Photographer: Stefan Wermuth/Bloomberg

In late January, Donald Trump launched his second presidential term with two executive actions that struck directly at Geneva, the lakeside city long known as the epicenter of global public health, peacemaking and diplomacy.

The president pulled the US out of the World Health Organization — which received $1.3 billion from the government for its last two-year period — and moved to cancel most contracts held by US Agency for International Development, an effort that’s currently being challenged in court.

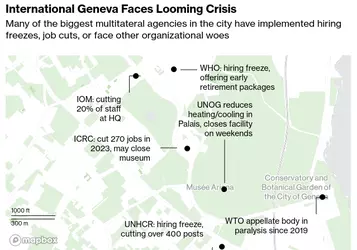

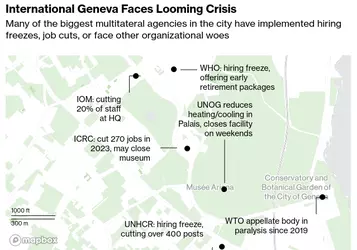

These changes were immediately felt in the canton. In addition to being where the Geneva Conventions were signed and the first thaw in the Cold War took place, the city is also home to 38 international organizations that employ 29,000 people, spend some $7 billion each year and support around 400 NGOs. Up until recently, that ecosystem received generous assistance from the US. Now, the WHO is scrambling to find alternate donors, and Geneva’s councillors proposed using $11 million from the local budget to cover NGO salaries in the wake of the USAID cuts. The plan is still under review.

Across the city, other agencies are expecting the cuts to make existing funding crises even worse. The International Committee of the Red Cross, whose main office occupies a hilltop overlooking the UN campus, announced a hiring freeze, after shedding 270 jobs at its Swiss headquarters in 2023. Down the street, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees said at least 400 jobs will disappear. The International Organization for Migration is letting more than 250 employees go in Geneva following an unprecedented 30% cut in donor funding.

Geneva’s problems didn’t start under the current American president. The global turn towards isolationism has been gaining momentum for years, and Switzerland’s pivot away from strict neutrality — central to the country’s efforts to pitch itself as the world’s impartial arbiter — started in the early 2000s. In light of Trump’s “America First” agenda, however, Geneva is now in the uncomfortable position of representing a liberal order that’s no longer ascendant.

“The idea of international cooperation, of being a globalist, used to be a cool thing to be and say, but in most countries, national interest has become way more important,” says Joost Pauwelyn, a professor in international trade law at the Graduate Institute in Geneva. “That’s not good for Geneva.”

Signs of this shift are all over the UN’s historic Palais des Nations complex, where temperatures are set to 79 degrees in summer and 69 degrees in winter to save on electricity bills, and the complex closes on weekends and holidays to bring down staffing costs. The measures were implemented last April because 51 out of 193 member states had not fully paid their 2023 dues, according to Tatiana Valovaya, the UN’s Director-General in Geneva. Nearly a year later, financial pressures have intensified. As of March, the number of countries late on their payments rose to 121, according to UN data. Just China and the US, which together owed $1.14 billion last year alone, were among them.

Geneva’s Red Cross Museum is warning that it risks closure after the ICRC cut hundreds of jobs.Photographer: Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images

“The primary reason why you have this liquidity crisis is because member states are not paying in full and on time, and that’s in part because of a focus on self-interest,” said Maya Ungar, a UN expert at the International Crisis Group in New York.

A White House-issued questionnaire circulating among US-funded international agencies and NGOs in Geneva is a further indication of how the Trump administration is reassessing its commitments. To appeal for continued funding, respondents must confirm that “this is not a climate or ‘environmental justice’ project,” and answer questions about whether their work will “reinforce U.S. sovereignty by limiting reliance on international organizations or global governance structures (e.g., UN, WHO).”

Philippe Mottaz, founder and editor of the online Geneva Observer, said the questionnaire left many residents baffled.

“The mood ranges from sheer panic to extreme anger at the way it’s being done to extreme worry about the way it’s going to go,’’ he said. He predicted that imminent job cuts combined with the loss of high-level summits will amount to a “significant attrition” of Geneva’s role on the international stage.

Neutrality Drift

For decades, Swiss multilateralism coexisted, sometimes uneasily, with the country’s longtime commitment to neutrality. That came to an end in the early 2000s, when Switzerland joined the UN and International Criminal Court. The obligation to adhere to international humanitarian law wasn’t an issue in 2021, when Joe Biden sat down in Geneva with Russian President Vladimir Putin to reset relations between the two superpowers. Less than a year later, however, such a meeting would be impossible.

Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin at the U.S.-Russia summit in Geneva in June 2021.Peter Klaunzer/Swiss Federal Office of Foreign Affairs/Bloomberg

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, front, arrives in Riyadh on Feb. 17 for talks with US Secretary of State Marco Rubio. Source: Russian Foreign Ministry/Anadolu/Getty Images

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Switzerland’s ICC membership meant that Putin risked his freedom if he set foot in the country. The court had issued an arrest warrant for his policy of forcibly relocating Ukrainian children to Russia. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was put in the same position after the court indicted him over his prosecution of Israel’s war on Hamas.

Now, high-stakes negotiations that once would have been set in Geneva are increasingly held elsewhere. In February, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov sat down in Riyadh for the first high-level meeting between the two countries in nearly three years. In March, Ukrainian President Volodomyr Zelensky traveled to the Saudi capital for ceasefire discussions, and Trump and Putin are expected to meet there later this year. Earlier this year, a tentative peace deal between Israel and Hamas was brokered in Qatar.

Switzerland’s 2022 decision to adopt European Union sanctions on Russia has also impacted the city’s key commodities sector. Before sanctions went into effect, three-quarters of all crude Russian oil and oil product exports were handled through Geneva, according to lobby group SuisseNegoce. Now, most dealmaking happens from sanctions-free Dubai, which is home to about 22,000 traders, according to the Dubai Multi Commodities Centre — an increase of about a third since 2022, according to one report. Litasco, the trading unit of Russia’s Lukoil PJSC, has relocated several key employees to Dubai from its Geneva office.

The city is still home to giants Gunvor, Trafigura, Mercuria and Vitol, whose record profits in recent years led to a surge in the canton’s tax revenue, but the industry’s geographic footprint is changing, said SuisseNegoce Secretary-General Florence Schurch. Before the sanctions, she said, a trading house would have four employees in Geneva for each one in Dubai. Now, for some, it’s the reverse.

In financial terms, the city has done well in recent years. Multinationals saw their employee headcount rise to 112,000 between 2019 and 2023 — a nearly 5% increase. A February announcement that SGS SA, the world’s biggest goods-inspection company, plans to leave its Beaux-Arts headquarters for the tax haven of Zug exacerbated concerns of an exodus. The payrolls of international organizations climbed 9% over the past five years to about 29,000, but locals are now bracing for the latter number at least to drop sharply.

The UN’s XIX Hall in the Palais des Nations in 2024, after it was renovated with money provided by Qatar.Photographer: Capucine Veuillet/Hans Lucas/Redux

Within multilateral institutions, the expectation is not that international Geneva will disappear, but that power dynamics will shift as other authoritarian-minded countries step in to fill the gap left by the US.

China is already moving to claim a larger role in international institutions. After placing diplomats in top jobs at the WHO and International Telecommunications Union over the past decade, a recent study chronicled how the country is focused on grooming a future generation of multilateral leaders. One part of that strategy is to secure more internship spots in the UN system.

The US retreat from the UN is a “great way for China to be a leader of the Global South,” Mottaz said, adding that it doesn’t even require them to increase their financial commitments. For Gulf states such as the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, which recently spent $40 million to renovate two wood-panelled meeting halls at the Palais des Nations, the vacuum has presented another opportunity. They “are burnishing their image’’ at a bargain price, he said.

The longtime resident of Geneva and former head of news at Swiss broadcaster RTS described the current moment as “the end of a historical cycle.” As the US tries to dismantle the multilateral system while figuring out what an America First foreign policy might look like, Mottaz said, “Geneva, being at the heart of it, is being massively impacted.’’

— With assistance from Iain Marlow

Bloomberg (archive.ph)

By Hugo Miller

2025-03-25 05:00:21GMT

Geneva boasts 38 international organizations that employ 29,000 people, spend some $7 billion each year and support around 400 NGOs — all of which are now facing funding challenges.Photographer: Stefan Wermuth/Bloomberg

In late January, Donald Trump launched his second presidential term with two executive actions that struck directly at Geneva, the lakeside city long known as the epicenter of global public health, peacemaking and diplomacy.

The president pulled the US out of the World Health Organization — which received $1.3 billion from the government for its last two-year period — and moved to cancel most contracts held by US Agency for International Development, an effort that’s currently being challenged in court.

These changes were immediately felt in the canton. In addition to being where the Geneva Conventions were signed and the first thaw in the Cold War took place, the city is also home to 38 international organizations that employ 29,000 people, spend some $7 billion each year and support around 400 NGOs. Up until recently, that ecosystem received generous assistance from the US. Now, the WHO is scrambling to find alternate donors, and Geneva’s councillors proposed using $11 million from the local budget to cover NGO salaries in the wake of the USAID cuts. The plan is still under review.

Across the city, other agencies are expecting the cuts to make existing funding crises even worse. The International Committee of the Red Cross, whose main office occupies a hilltop overlooking the UN campus, announced a hiring freeze, after shedding 270 jobs at its Swiss headquarters in 2023. Down the street, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees said at least 400 jobs will disappear. The International Organization for Migration is letting more than 250 employees go in Geneva following an unprecedented 30% cut in donor funding.

Geneva’s problems didn’t start under the current American president. The global turn towards isolationism has been gaining momentum for years, and Switzerland’s pivot away from strict neutrality — central to the country’s efforts to pitch itself as the world’s impartial arbiter — started in the early 2000s. In light of Trump’s “America First” agenda, however, Geneva is now in the uncomfortable position of representing a liberal order that’s no longer ascendant.

“The idea of international cooperation, of being a globalist, used to be a cool thing to be and say, but in most countries, national interest has become way more important,” says Joost Pauwelyn, a professor in international trade law at the Graduate Institute in Geneva. “That’s not good for Geneva.”

Signs of this shift are all over the UN’s historic Palais des Nations complex, where temperatures are set to 79 degrees in summer and 69 degrees in winter to save on electricity bills, and the complex closes on weekends and holidays to bring down staffing costs. The measures were implemented last April because 51 out of 193 member states had not fully paid their 2023 dues, according to Tatiana Valovaya, the UN’s Director-General in Geneva. Nearly a year later, financial pressures have intensified. As of March, the number of countries late on their payments rose to 121, according to UN data. Just China and the US, which together owed $1.14 billion last year alone, were among them.

Geneva’s Red Cross Museum is warning that it risks closure after the ICRC cut hundreds of jobs.Photographer: Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images

“The primary reason why you have this liquidity crisis is because member states are not paying in full and on time, and that’s in part because of a focus on self-interest,” said Maya Ungar, a UN expert at the International Crisis Group in New York.

A White House-issued questionnaire circulating among US-funded international agencies and NGOs in Geneva is a further indication of how the Trump administration is reassessing its commitments. To appeal for continued funding, respondents must confirm that “this is not a climate or ‘environmental justice’ project,” and answer questions about whether their work will “reinforce U.S. sovereignty by limiting reliance on international organizations or global governance structures (e.g., UN, WHO).”

Philippe Mottaz, founder and editor of the online Geneva Observer, said the questionnaire left many residents baffled.

“The mood ranges from sheer panic to extreme anger at the way it’s being done to extreme worry about the way it’s going to go,’’ he said. He predicted that imminent job cuts combined with the loss of high-level summits will amount to a “significant attrition” of Geneva’s role on the international stage.

Neutrality Drift

For decades, Swiss multilateralism coexisted, sometimes uneasily, with the country’s longtime commitment to neutrality. That came to an end in the early 2000s, when Switzerland joined the UN and International Criminal Court. The obligation to adhere to international humanitarian law wasn’t an issue in 2021, when Joe Biden sat down in Geneva with Russian President Vladimir Putin to reset relations between the two superpowers. Less than a year later, however, such a meeting would be impossible.

Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin at the U.S.-Russia summit in Geneva in June 2021.Peter Klaunzer/Swiss Federal Office of Foreign Affairs/Bloomberg

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, front, arrives in Riyadh on Feb. 17 for talks with US Secretary of State Marco Rubio. Source: Russian Foreign Ministry/Anadolu/Getty Images

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Switzerland’s ICC membership meant that Putin risked his freedom if he set foot in the country. The court had issued an arrest warrant for his policy of forcibly relocating Ukrainian children to Russia. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was put in the same position after the court indicted him over his prosecution of Israel’s war on Hamas.

Now, high-stakes negotiations that once would have been set in Geneva are increasingly held elsewhere. In February, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov sat down in Riyadh for the first high-level meeting between the two countries in nearly three years. In March, Ukrainian President Volodomyr Zelensky traveled to the Saudi capital for ceasefire discussions, and Trump and Putin are expected to meet there later this year. Earlier this year, a tentative peace deal between Israel and Hamas was brokered in Qatar.

Switzerland’s 2022 decision to adopt European Union sanctions on Russia has also impacted the city’s key commodities sector. Before sanctions went into effect, three-quarters of all crude Russian oil and oil product exports were handled through Geneva, according to lobby group SuisseNegoce. Now, most dealmaking happens from sanctions-free Dubai, which is home to about 22,000 traders, according to the Dubai Multi Commodities Centre — an increase of about a third since 2022, according to one report. Litasco, the trading unit of Russia’s Lukoil PJSC, has relocated several key employees to Dubai from its Geneva office.

The city is still home to giants Gunvor, Trafigura, Mercuria and Vitol, whose record profits in recent years led to a surge in the canton’s tax revenue, but the industry’s geographic footprint is changing, said SuisseNegoce Secretary-General Florence Schurch. Before the sanctions, she said, a trading house would have four employees in Geneva for each one in Dubai. Now, for some, it’s the reverse.

In financial terms, the city has done well in recent years. Multinationals saw their employee headcount rise to 112,000 between 2019 and 2023 — a nearly 5% increase. A February announcement that SGS SA, the world’s biggest goods-inspection company, plans to leave its Beaux-Arts headquarters for the tax haven of Zug exacerbated concerns of an exodus. The payrolls of international organizations climbed 9% over the past five years to about 29,000, but locals are now bracing for the latter number at least to drop sharply.

The UN’s XIX Hall in the Palais des Nations in 2024, after it was renovated with money provided by Qatar.Photographer: Capucine Veuillet/Hans Lucas/Redux

Within multilateral institutions, the expectation is not that international Geneva will disappear, but that power dynamics will shift as other authoritarian-minded countries step in to fill the gap left by the US.

China is already moving to claim a larger role in international institutions. After placing diplomats in top jobs at the WHO and International Telecommunications Union over the past decade, a recent study chronicled how the country is focused on grooming a future generation of multilateral leaders. One part of that strategy is to secure more internship spots in the UN system.

The US retreat from the UN is a “great way for China to be a leader of the Global South,” Mottaz said, adding that it doesn’t even require them to increase their financial commitments. For Gulf states such as the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, which recently spent $40 million to renovate two wood-panelled meeting halls at the Palais des Nations, the vacuum has presented another opportunity. They “are burnishing their image’’ at a bargain price, he said.

The longtime resident of Geneva and former head of news at Swiss broadcaster RTS described the current moment as “the end of a historical cycle.” As the US tries to dismantle the multilateral system while figuring out what an America First foreign policy might look like, Mottaz said, “Geneva, being at the heart of it, is being massively impacted.’’

— With assistance from Iain Marlow