Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker is joined by first lady MK Pritzker during a rally to kick off his reelection campaign for a third term as governor at the Grand Crossing Park Fieldhouse in Chicago on June 26, 2025. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker is joined by first lady MK Pritzker during a rally to kick off his reelection campaign for a third term as governor at the Grand Crossing Park Fieldhouse in Chicago on June 26, 2025. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

Democratic Gov. JB Pritzker this week

set out to make history, launching his bid to become the first Illinois governor since the 1980s to be elected to more than two terms in office.

A win next year also would make Pritzker, 60, the first Democrat ever in Illinois to win three terms.

Republican James R. Thompson was Illinois’ longest-serving governor, winning election four times straight and holding the office from 1977 to 1991.

A century earlier, when the Grand Old Party was a new force in politics, Republican Richard Oglesby won three nonconsecutive elections, in 1864, ’72 and ’84, although he resigned 10 days after being sworn in for his second term to join the U.S. Senate. Two other Republicans, Dwight Green in 1948 and William Stratton in 1960, made unsuccessful third-term attempts, losing to Democrats Adlai Stevenson II and Otto Kerner, respectively.

Pritzker is not expected to have significant competition for the Democratic primary in March and it remains to be seen whether any high-profile Republicans will mount a campaign to challenge him in November 2026. He’s also publicly

flirted with the idea of running for president in 2028.

So as

Pritzker embarks on another campaign, here’s a look back at how the Hyatt Hotels heir went from political neophyte to 43rd governor of Illinois and potential Democratic presidential contender.

Fortune and tragedy

Pritzker’s story begins when his great-grandfather Nicholas J. Pritzker came to Chicago from Kyiv in 1881 to escape the anti-Jewish Russian pogroms in present-day Ukraine.

Nicholas Pritzker eventually founded a law firm, but the family’s business empire got going in the next generation, when one of Nicholas’ sons and

JB’s grandfather, A.N. Pritzker, and great-uncle began investing in real estate and other ventures. The family is best known for Hyatt, but other

high-profile investments have included Royal Caribbean Cruises,

Ticketmaster and credit bureau TransUnion.

Today, the extended Pritzker clan is the

sixth-richest family in America, with an estimated fortune of $41.6 billion, according to Forbes. (JB’s share is

estimated at $3.7 billion.)

Born into affluence in California in 1965, Jay Robert Pritzker — named after his two uncles and called JB for short — didn’t have an idyllic childhood. Both of his parents died before he turned 18.

His father, Donald, died of a heart attack in 1972 at age 39, and his mother, Sue, struggled with alcoholism. She died a decade later, almost to the day, when she leaped out of a tow truck that was pulling her car, and she was run over.

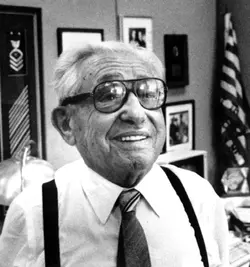

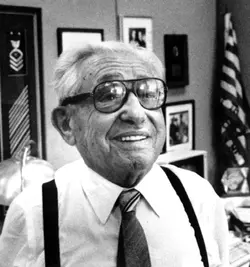

A.N. Pritzker, Gov. JB Pritzker's late grandfather, circa 1985. (Chicago Tribune archive photo)

A.N. Pritzker, Gov. JB Pritzker's late grandfather, circa 1985. (Chicago Tribune archive photo)

Despite her struggles, Sue Pritzker’s philanthropy and involvement in the Democratic Party inspired JB’s interest in politics and activism,

particularly in the area of reproductive rights.

Political ambitions

While he was only first elected to public office in 2018, Pritzker has long nursed political ambitions.

After graduating from Duke University in the 1980s, he worked on Capitol Hill as an aide to Democratic U.S. Sens. Terry Sanford of North Carolina and Alan Dixon of Illinois.

Returning to the Chicago area to attend law school at Northwestern University in the early 1990s, he formed

Democratic Leadership for the 21st Century. The group sought to bring more young voices into the party and helped spur the careers of several prominent Illinois officials and Democratic operatives, including Illinois Senate President Don Harmon, an Oak Park Democrat.

In 1998, Pritzker made his first run for public office, finishing in a disappointing third place in a Democratic primary to replace 24-term U.S. Rep. Sidney Yates. The

winner was Jan Schakowsky. She went on to win the general election and has held the seat since, although Schakowsky recently announced

she isn’t running for another term.

“Could I live a happy life without ever running for public office again?”

Pritzker said in a Tribune profile after losing the race. “I suppose that I can imagine not running, but I feel I have something important that I can do. And my skin is far thicker now.”

Candidates in the 9th Congressional District JB Pritzker, from left, state Sen. Howard Carroll and state Rep. Jan Schakowsky wait for their cue to step onto a stage at the beginning of a debate on Jan. 25, 1998, at the Ezra Habonim Synagogue in Skokie. (John Lee/Chicago Tribune)

Candidates in the 9th Congressional District JB Pritzker, from left, state Sen. Howard Carroll and state Rep. Jan Schakowsky wait for their cue to step onto a stage at the beginning of a debate on Jan. 25, 1998, at the Ezra Habonim Synagogue in Skokie. (John Lee/Chicago Tribune)

It would be two decades before he’d put his name on the ballot again. But ambitions lingered.

In a 2008 phone call secretly recorded by federal investigators, Pritzker spoke with then-Gov. Rod Blagojevich, whose campaigns he’d contributed to, as the Chicago Democratic governor schemed over who to appoint to the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by then-President-elect Barack Obama. On the call,

first revealed by the Tribune during the 2018 governor’s race, Pritzker expressed disinterest in the Senate appointment but suggested Blagojevich might make him state treasurer if the position became vacant. Blagojevich and Pritzker also were recorded discussing various Black officials who were potential Senate appointees in language that

caused a stir during the 2018 campaign.

Aside from his own aspirations, Pritzker was a

major backer of Hillary Clinton in both her presidential bids, even as his

older sister Penny served as finance chair for Illinois’ favorite son, Obama, in 2008. Ahead of the 2016 election, JB Pritzker and his wife, MK, gave $15.6 million to pro-Clinton political action committee Priorities USA Action.

Outside politics

Out of the political spotlight, Pritzker built up his resume as an investor and philanthropist.

While his name and fortune are closely associated with Hyatt, Pritzker only worked for the family hotel business as a teenager.

He made his mark in the business realm through

New World Ventures, a tech-focused investment fund founded with his older brother, Anthony, and later renamed Pritzker Group Venture Capital. The brothers also started Pritzker Group, which, in addition to the venture fund, includes private equity and asset management components.

In 2012, Pritzker founded the nonprofit tech incubator 1871 to help spur Chicago’s tech sector, later collaborating closely with then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel. In a 2014 profile highlighting the project,

Chicago magazine dubbed Pritzker “The Other Mayor of Chicago.”

JB Pritzker, then Chicago Next co-chair speaks while Mayor Rahm Emanuel listens as they visited the offices of Sprout Social on Oct. 17, 2012. (Nancy Stone/Chicago Tribune)

JB Pritzker, then Chicago Next co-chair speaks while Mayor Rahm Emanuel listens as they visited the offices of Sprout Social on Oct. 17, 2012. (Nancy Stone/Chicago Tribune)

In the philanthropic world, Pritzker helped

found and fund the Illinois Holocaust Museum in Skokie, and he, along with MK, launched the Pritzker Family Foundation in 2001, which funds initiatives in early childhood education and other areas.

Repudiating Rauner and beating Bailey

Spurred by Clinton’s loss to Republican Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election and the bruising budget battles in Springfield between then-Gov. and GOP multimillionaire Bruce Rauner and the Democratic-controlled legislature,

Pritzker entered the 2018 campaign for Illinois governor.

Defeating political scion Chris Kennedy and then-state Sen. Daniel Biss of Evanston in the

Democratic primary, Pritzker ultimately

poured more than $170 million of his own money into the campaign. Combined with $79 million for Rauner, including $50 million from the incumbent himself and $22.5 million from billionaire Citadel CEO Ken Griffin, it resulted in what’s believed to be the most expensive governor’s race in U.S. history, which

Pritzker won by nearly 16 points.

Four years later,

Pritzker spent another $167 million to beat back a challenge from conservative southern Illinois state Sen. Darren Bailey, who got backing from billionaire ultraconservative Richard Uihlein, founder of the Uline packaging supplies firm.

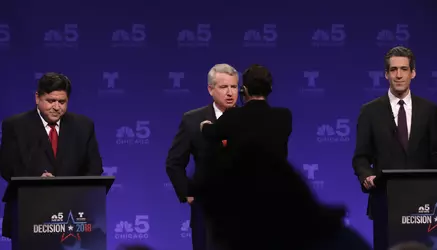

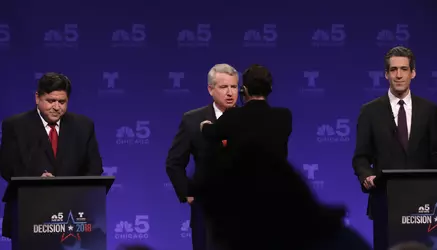

Democratic candidates for Illinois governor, J.B. Pritzker, from left, Chris Kennedy and Daniel Biss take their positions before the first televised 2018 Illinois Democratic gubernatorial forum at WMAQ-Ch. 5 studios on Jan. 23, 2018. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

Democratic candidates for Illinois governor, J.B. Pritzker, from left, Chris Kennedy and Daniel Biss take their positions before the first televised 2018 Illinois Democratic gubernatorial forum at WMAQ-Ch. 5 studios on Jan. 23, 2018. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

Pritzker’s 2022 spending total included

$27 million he gave to the Democratic Governors Association, which aired ads during the GOP primary labeling Bailey as too conservative. The move was a thinly veiled attempt to set up what Pritzker’s team saw as an easier general election matchup, boosting Bailey among Republican primary voters over then-Aurora Mayor Richard Irvin, backed by

$50 million from Pritzker nemesis Griffin.

Pritzker beat Bailey by 13 points that fall.

Through the end of 2022, Pritzker spent nearly $350 million on the two campaigns. Over the past two years, he’s deposited another $25 million in his campaign account and had $3.4 million remaining at the end of April, state records show.

Fiscal focus

A hallmark of Pritzker’s two terms in office has been his handling of the state’s chronically shaky finances.

While

he failed to convince voters in 2020 to amend the state constitution to create a graduated-rate income tax, an effort into which he sunk $58 million, Pritzker has received high marks from ratings agencies and other observers for his handling of the budget. After years of downgrades, the state has seen its credit rating raised by all the major agencies, though it still ranks near the bottom compared to the other 49 states.

Spending has increased by nearly a third during his time in office, without adjusting for inflation. But the state largely has avoided using gimmicks to balance the budget on Pritzker’s watch and received its first credit upgrades in decades.

Tighter financial times have returned, however, with the state budget that takes effect July 1

cutting funding for health insurance for noncitizen immigrants younger than 65 and pausing Pritzker’s proposed expansion of state-funded preschool programs, among other trims.

Rather than trying again to fix a state tax system he once described as “unfair” and “inadequate,”

Pritzker has instead blamed Trump and his economic policies for the state’s latest budget woes.

Progressive bona fides

Aided by overwhelming Democratic majorities in the state legislature, which he helped secure through his political largesse, Pritzker has built a resume almost any governor in the party would be happy to claim.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker signs legislation to ban military style firearms on Jan. 10, 2023, in Springfield. Gun control advocate Delphine Cherry, second from right, who lost two of her children, Tyesa and Tyler, to gun violence becomes emotional during the signing. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

Gov. J.B. Pritzker signs legislation to ban military style firearms on Jan. 10, 2023, in Springfield. Gun control advocate Delphine Cherry, second from right, who lost two of her children, Tyesa and Tyler, to gun violence becomes emotional during the signing. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

His accomplishments in the legislature include

raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour, enshrining abortion rights in state law,

legalizing recreational marijuana while expunging prior convictions, and enacting a

$45 billion infrastructure program, the largest in state history.

And that was just his first year.

He has also enacted an

ambitious energy policy that aims to make Illinois’ energy generation carbon-free by 2050, as well as an overhaul of the criminal justice system that has

eliminated cash bail.

In one of the first acts of his second term, Pritzker in early 2023

signed a sweeping gun ban that prohibits the sale or possession of a long list of high-powered semiautomatic firearms and high-capacity ammunition magazines, a response to the mass shooting at Highland Park’s Fourth of July parade months earlier. While facing ongoing legal challenges, the

law has remained in force.

More recently, he’s taken on what he describes as the predatory practices of health insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers.

He’s also made moves,

with mixed results, to position Illinois as a leader in emerging industries such as electric vehicles and quantum technology.

Crises and controversies

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 tested Pritzker’s leadership and, in some ways, ended a brief honeymoon period he had with some members of the legislature’s Republican minority. Decisions to shut schools and issue a stay-at-home order brought the state government into people’s lives in unprecedented ways.

Aside from conservative criticism over Pritzker’s use of executive power, the pandemic exposed problems at state agencies under his control, including an

outbreak at a state-run veterans home in LaSalle that led to 36 deaths and an

overwhelmed unemployment system that elicited some bipartisan criticism.

The Choate Mental Health and Developmental Center seen on Aug. 26, 2022, in Anna, Illinois. (Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune)

The Choate Mental Health and Developmental Center seen on Aug. 26, 2022, in Anna, Illinois. (Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune)

His administration also has

come under fire for continued problems at the beleaguered Illinois Department of Children and Family Services and the

handling of resident mistreatment at homes for the developmentally disabled. And a state

inspector general has found rampant fraud among state employees who abused the federal government’s Paycheck Protection Program, a pandemic-era lifeline for businesses.

Pritzker’s administration also was forced to respond when Republican Gov. Greg Abbott of Texas in 2022 began sending busloads of migrants from the southern border to Chicago, creating a crisis for the city and state and inflaming tensions with Mayors Lori Lightfoot and

Brandon Johnson.

The governor has also faced criticism for working with legislative

Democrats to exclude Republicans from the process of allocating funds for local infrastructure projects and for not taking significant enough steps to

strengthen government ethics laws, despite a sprawling federal corruption probe involving state lawmakers and local officials and a series of high-profile convictions during his tenure.

Higher ambitions

A vociferous Trump critic, Pritzker has long been believed to harbor presidential ambitions, speculation he’s done little to quell even as he has professed his dedication to Illinois.

The

governor lobbied hard to bring last year’s Democratic National Convention to Chicago,

serving as de facto host for an event widely seen as a success, at least until Trump emerged victorious in November.

Gov. JB Pritzker speaks on Aug. 20, 2024, during the Democratic National Convention at the United Center. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

Gov. JB Pritzker speaks on Aug. 20, 2024, during the Democratic National Convention at the United Center. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

Gov. JB Pritzker greets people after announcing his candidacy for a third term on June 26, 2025, at the Grand Crossing Park Field House in Chicago. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

Gov. JB Pritzker greets people after announcing his candidacy for a third term on June 26, 2025, at the Grand Crossing Park Field House in Chicago. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

Pritzker, at least publicly,

stood behind President Joe Biden until he dropped out, declining to mount a primary challenge to a sitting president or to enter the fray when Vice President

Kamala Harris became the consensus pick of party leaders.

He was vetted to join Harris on the ticket but was passed over in favor of Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz.

In 2023,

he launched Think Big America, a dark money group that has backed abortion rights ballot measures and pro-abortion rights candidates across the country. He’s also poured money into two

recent Wisconsin Supreme Court races, backing candidates that reclaimed and then maintained a liberal majority in the pivotal swing state.

In addition to running his campaign for reelection next year, Pritzker is putting his force behind

Lt. Gov. Juliana Stratton, his two-time running mate, in her Democratic primary bid for U.S. Senate.

Heading into 2026, a big question is whether and how quickly Pritzker will pivot to a 2028 presidential bid if he wins a third term as governor.