Sarah Vital looks out the window of her bedroom in Springfield, Ohio. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

By Danielle Paquette and Obed Lamy

July 19, 2025 at 5:00 a.m. EDT

SPRINGFIELD, Ohio — She hadn’t seen cracks like that since the earthquake. Now they snaked up her buttercream dining room walls and etched tiny ravines in the ceiling.

“Crazy,” Fernande Vital said to her husband as they eyed the damage. “They’re driving me crazy.”

Clearly, they’d spread. Like the scars on all those buildings back home, she told a construction-worker friend who, as a fellow Haitian, understood. He’d also survived the 7.0 mega-tremors that once leveled much of their island nation.

Fernande had figured calamity wouldn’t trail them to America, land of the free, home of the Kardashian opulence on her teenage daughter’s TikTok feed. Not that glitz had ever been the goal. Her family of five sought the basics in southwestern Ohio: Assembly line work. Sunday service. A banged-up Honda minivan. A jar of faux carnations. Safety.

Their only indulgence had been the house on Chestnut Avenue. Slate gray with a wraparound porch, the century-old Folk Victorian hit the market in the final leg of the 2024 presidential campaign. Hurry, this will go fast! Back then, the Vitals paid scarce attention to politicians who, in their view, flipped and flopped. A “beautiful, restored 4 bedroom home,” as the Zillow listing gushed, dangled a future they could touch in the Rust Belt city they’d grown to love. They’d glossed over the last line. Sold as is.

The couple had settled in Springfield during President Donald Trump’s first term and saved money through the Biden administration. Business leaders in their reliably red county praised immigrants for reviving the local economy. Americans struggled to pass a drug test, one factory boss told a TV news crew. Not Haitians.

Fernande earned $21 an hour at a Japanese automotive plant, monitoring robots forging car parts, while her husband, Rocher, led a strip-mall church. Even as the GOP and some of their neighbors called for mass deportations, the Vitals were sure nobody meant them, immigrants here legally.

So last July, they made a down payment of $8,000, their entire nest egg. In August, they moved in, installed lace curtains and hung a family portrait in the dining room. One month later came the cracks.

The Vitals moved into their house on Chestnut Avenue last August. One month later, their dream there began fracturing. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

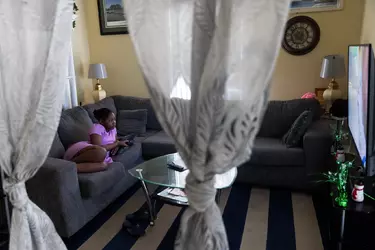

“Moana” is a favorite diversion at home for 9-year-old Rocherline Vital. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

Around the same time, Trump falsely claimed that Haitians here were eating pets and pledged “the largest deportation in the history of our country,” starting with Springfield. Bomb threats closed schools. Neo-Nazis marched through town with swastika flags, decrying the immigrants as an “invasion.”

The Vitals huddled in front of the television, watching the spectacle unfold. Many Haitians they knew went into lockdown, trekking out solely for necessities. In WhatsApp groups, some friends wrote that strangers had screamed at them on the street, “Go home!” Others shared plans to leave. Fernande pressed her family to stay inside, and they mostly did, which meant more time staring at the walls. Soon her 17-year-old daughter, Sarah, pointed to her bedroom ceiling. More cracks.

“Everything is breaking,” Fernande said — their house, their sense of security, the life they’d charted over plates of stewed chicken and rice.

What to do next? She was as unsure as her husband. Pitying their bad luck, their construction-worker friend offered his labor for free, warning that inaction could spell mold or worse. The Vitals just needed to fund the drywall, stain-blocking sealer and other supplies from Home Depot — $7,000, he estimated.

That didn’t include the cost of a structural engineer, who would be able to tell if anything was at risk of collapse. At this moment, there was only Fernande’s husband running a finger along a wiggly line that had just emerged in the corner. Above it, other fissures had widened, and fresh ridges bulged in the ceiling.

“Voilà,” Rocher said flatly. Sarah, sprawled on the couch, didn’t look up from her phone.

“Crazy,” Fernande repeated.

Their dilemma was global. Their dilemma was domestic. Their family was being tested by the devil, Fernande thought. She and her husband could agree on one thing: It was past time to start repairs.

But what could be fixed in a world that seemed to be falling apart? It was hard to justify doubling down on an investment in a country that didn’t seem to want them. Even harder to give up on what their piece of America had represented.

“Our legacy,” Fernande declared after signing the closing documents. She imagined growing old on Chestnut Avenue and building some real estate wealth for the kids to inherit, hoping the next generation wouldn’t need to sweat over an assembly line.

That dream had fractured into precarious options. Returning to Haiti was too risky. The gangs that controlled most of the capital roamed their old neighborhood with assault rifles. Canada would be safer, yet they’d have to save every dollar to relocate to a third country, which meant selling the house, and Fernande doubted anyone would match the $175,000 they had paid for this mess. The couple could sink permanently into the red; they’d put only 5 percent down on a 30-year mortgage.

“I want to leave,” she said vaguely.

Her husband pushed back. Buying the house, in his view, had been an act of faith. “If we got it,” he said, “then it was meant to be.”

They could mend the worst problems, gradually, Rocher believed, and cross their fingers that a structural engineer would uncover no urgent defects. Their legal status faced more scrutiny than ever, though. No renovation could shelter the deported.

The Vitals hoped the home would become a legacy for their children and an anchor for their lives in America. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

Three decades of marriage. Three kids. One move across the Western Hemisphere, swapping Port-au-Prince’s misty hills and ocean views for the colder, flatter, decidedly more beige land of Springfield. Two career transformations. Two wobbly attempts to learn English.

Still, the couple liked to joke that they hadn’t changed much.

Fernande, 54, was the steely one. A pragmatist, watchful and proud, she’d rather keep to herself. If she hurt your feelings? Oh well.

Rocher, a few months younger, remained the dreamer. An optimist, extroverted since boyhood, he’d started a Christian church in Haiti and founded another one here at the Southern Village Shopping Center. He couldn’t not answer his phone.

What an odd pairing, Fernande recalls thinking when Rocher first asked her out. Skinny and shorter, he hardly seemed husband material. She prayed about it, and the answer arrived in a dream: As she tried to hide behind mountains, around each bend waited Rocher.

As a minister, Rocher Vital saw buying property in Springfield as an act of faith. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

At the church that her husband pastors, Fernande Vital is "Madame Pasteur." (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

They married in 1995. Next came Mardocher, now 24, Sarah, 17, and Rocherline, 9. Fernande excelled as a math teacher and then an assistant principal, while Rocher tended his congregation. They might have stayed in Haiti forever if the gangs hadn’t taken over and a gunman hadn’t threatened to kill Rocher if he didn’t hand over his church’s cash. Attackers targeted those in charge of anything, including pastors, one of whom got kidnapped during a live-streamed service.

Violence was surging anew in 2019 when the Vitals began hearing in WhatsApp chats about an Ohio city with a labor shortage. Jobs aplenty here, a friend had reported; some plants had even hired interpreters fluent in Haitian Creole. And Haitians still qualified for the U.S. government’s temporary protected status granted after the 2010 earthquake and rise of organized crime.

Fernande and Rocher saw their chance, joining what officials later estimated to be 15,000 immigrants in this pocket of the Midwest. Springfield, population 59,000, wasn’t equipped for so many newcomers crowding grocery stores, health clinics, classrooms and the DMV. Lines grew longer, residents complained, and the language barrier didn’t help. Then a Haitian driver with an invalid license struck a school bus, killing an 11-year-old boy, and the accident grabbed the attention of far-right pundits, who soon amplified a Facebook rumor that these foreigners were trapping and cooking their neighbors’ cats and dogs.

One day after Trump’s inauguration, Fernande wondered if they could undo the house sale.

“You want to leave something for the kids,” she said, “but not like this.”

“We are not making any emotional decisions,” Rocher replied.

The family moved to Springfield from Port-au-Prince, the parents coming first and then, several years later, the three children finally joining them. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

His phone was ringing again, this time with welcome news. Sarah was off to perform with her high school dance team. Could she stay out afterward with her friends?

Even for a sullen teen, Sarah had seemed glum lately. The political chaos had rattled her, Rocher knew, long after he determined it was again safe to have a little fun.

See you at the show, he promised.

From his office marked “Pastor,” he could hear the choir rehearsing for Sunday service. The church hosted Bible study and English classes and birthday parties, as evidenced by the cluster of deflating gold balloons outside his door, but its three-hour worship every weekend was the social event for many of the congregants, since few ever hit the Main Street bars and most preferred to cook dinner at home.

“Create in me a pure heart, oh God,” the voices sang in lilting Creole.

By this May afternoon, 104 days into Trump’s second term, tensions in the city had cooled to a surprising quiet. The “largest deportation” had not started here. Not even close. Rocher had heard of only four people getting detained for reasons unclear, and nobody had flagged an immigration raid. The president hadn’t mentioned Springfield for two months, not since asserting to Congress that “entire towns” were “buckled under the weight of the migrant occupation.”

At home, Rocher and Fernande were more concerned about money. Grocery prices were up. Federal budget cuts had zapped housing aid and food banks that once buoyed his poorer congregants. Rocher wanted to help. “We’re in the same boat,” Fernande said to that. The pastor didn’t draw a church salary.

Their adult son was usually stocking shelves; a grocery store clerk, he was saving up for community college. Their giggly fourth-grader was preoccupied with the “Moana” soundtrack. Sarah felt stuck, at least until next year, when she planned to join the Army after graduating.

Her mother worked days. Her father had just picked up graveyard shifts at a Honda plant, clocking out at 4:30 a.m., sleeping on the couch for a couple of hours to avoid waking Fernande, and then driving Sarah and Rocherline to school in case bullies lurked on the bus. On some of those rides, Rocher’s phone rang, and Sarah understood he’d soon be off to help some unfortunate caller. She wished he wasn’t a pastor.

“Too much pressure,” she said.

Her mom’s stress revealed itself in headaches, so Sarah had stopped complaining about the cracks in the ceiling. Instead, she ordered light projectors on Temu that made her bedroom glow like the inside of a lava lamp.

Sarah will graduate from high school next year and wants to join the Army. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

Rocher hoped he could keep allowing such splurges, but no one knew how much longer Haitians would stay employment-eligible. Work permits for some already had expired, and several friends had lost their jobs at factories and warehouses. Rocher dreaded August, when the legal status shielding his family and thousands more in town was set to lapse. The Trump administration had moved up the renew-or-revoke deadline previously scheduled for February 2026 — “For no reason,” Rocher scoffed — though a federal-court decision blocking that would tee up more legal battles.

Amid the uncertainty, he asked God to protect them. God had molded him, a once-scrawny boy, into a leader whose followers framed a poster-sized portrait of him captioned, “We Appreciate Everything you Do.” God ensured the collection basket’s weekly haul covered the rent for their sanctuary, a former library branch with leftover upholstered chairs and faded geometric-patterned carpet.

God had brought legal help, too. Yet the immigration attorneys driving in from Dayton and Columbus and wherever else were no match for the demand. Free legal clinics filled quickly. So did their wait lists.

Rocher felt responsible for those gathered within the church’s mint-green walls. His flock. He taped up signs that said “KNOW YOUR RIGHTS,” printed guides on obtaining a green card and set out bowls of Skittles for those he prayed would stick around.

“I don’t cry,” he said, leaning back in his office swivel chair. “I say, ‘What can we do?’”

Three months earlier, roughly 300 heads bowed here. These days, the crowd had dropped off. Some had moved to places less name-checked by the president. Others called Rocher from home, still afraid to step out. He listened and offered Bible verses. A favorite hung behind his desk. Psalm 51:10. “Create in me a pure heart, oh God, and renew a steadfast spirit within me.”

Sarah, left, and other members of a high school dance team get ready for a special appearance. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

Sarah, left, relishes the sisterhood of Creole speakers she found on the dance team. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

The team performed at a May fundraiser to support the Haitian community in Springfield. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

Renewing his own steadfast spirit had worked before, he told people. Like the time in 2020, when his children were stuck with their aunt in Haiti awaiting documents to enter the United States. Rocher and Fernande had traveled ahead to find work, but the separation dragged on for three painful years — far longer than they’d anticipated.

One day Rocher realized: They needed an act of faith. So he and Fernande moved into a bigger Springfield rental and furnished a space for each of their kids, hanging up clothes as though they were already there. “Sleep well,” he’d bid their empty beds. Less than a month into this ritual, the children’s papers were approved, and the Vitals were reunited.

The “For Sale” sign on Chestnut Avenue also had beckoned like an omen. The couple rushed through a tour of the home, its occupants watching as they went room to room. No one else spoke Creole; the entire process was alien. Buyers were supposed to hire inspectors? In Haiti, they’d built a brick house that outlasted the monster earthquake. In America, their new purchase would deteriorate before their eyes.

“Unimaginable” was how Fernande described it.

Rocher had ached to spend the whole day here at his desk, browsing the latest immigration news on his laptop and picking Scripture for the next service. That was before the afternoon call about a woman in hospice who was out of groceries.

He’d driven his beat-up van to the store and bought bread, peanut butter and bananas, which cost about an hour’s labor on the Honda floor. He delivered it all personally, snapping a photo of the goods like an Uber Eats driver to comfort the woman’s family.

“There is always a call,” he said, switching off the office light.

Rocher tells a congregant goodbye after a Sunday service. His small church worships in a former library branch in a Springfield strip mall. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

At the service that Sunday, Rocher’s gray, three-piece suit exuded no whiff of sleeping on the couch. His voice boomed through a microphone. Loudspeakers throttled ear drums. Shoppers outside could hear him at the Dollar General.

“God, clean us,” he cried from the makeshift stage. “Purify us.”

Fernande stood in the first row, hands clasped, projecting a united front. Madame Pasteur. Mrs. Pastor.

For months, she’d been increasingly hesitant to allow visitors into the house on Chestnut Avenue. Here she could focus on church duties, like pouring red wine into little plastic cups for Communion. There would be no complaining in public. She was a role model, with four years left on her work permit. By her count, more than half of her co-workers at the auto plant were Haitian.

Companies needed them, Fernande told herself. This mantra helped her stand up straight and smile, even as she now doubted that the economic argument for Haitians in Springfield would matter to decision-makers in Washington.

The other worshipers nodded, clapped, shouted, “Thank you, God!” A woman in a red dress and matching pillbox hat crumpled against a pillar, trilling in tongues.

Rocher’s flock, while lively as ever, had shrunk again. Down to about 150 this morning, it appeared. He avoided politics in his freestyle sermons but invited lawyers at every opportunity to the Mission Church of God of Truth (or Mission Église de Dieu de la Vérité in French, Haiti’s other language). Several had visited since January to guide folks through what had become this congregation’s legal Hail Mary:

If the Trump administration axes temporary protected status for Haitians, and courts fail to thwart that move, those with clean records and asylum applications pending can’t be deported, the lawyers argued. At least technically they can’t.

Yes, the Haitians had read the reports about other immigrants with the right papers getting booted. Many would still pay steep attorney fees for a chance to stay. One woman named Nathalie, hospitalized with covid during the pandemic, was chipping away at a $60,000 medical bill. She had managed to work out a payment plan and, she said, would choose that burden over dodging bullets in Haiti. She closed her eyes and lifted her hands as her pastor preached.

“Guide us,” he roared.

For many Haitians in Springfield, the church's Sunday service is the big social event of the week. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

Rocher works graveyard shifts at the local Honda plant, not only to provide for his family but for his church. (Maddie McGarvey/For The Washington Post)

Rocher had been trying to conjure another breakthrough for his family: green cards, the State Department’s lottery or loopholes for religious workers. In the meantime, each had an asylum application pending. With legal permanent residency, he felt everything else would fall into place. They just had to keep doing the right things. Acts of faith.

Fernande was less confident. A judge might not rule on their cases for years. But hers was a Christian household, meaning her husband was the head of it. Rocher would interpret God’s plan for them.

The Vitals wouldn’t leave Springfield, at least not for now. They didn’t have the financial footing to move, anyway. Packing up would require transcending the cycle of paycheck to paycheck. The same went for buying drywall from Home Depot.

“Construction is postponed” was how he put it.

“Not an ideal situation” was her diplomatic reaction.

Their dilemma no longer existed. Rocher had made the big decision through a series of little decisions, like buying someone a bag of groceries instead of banking those dollars. All the while, he continued to evangelize about the American Dream. As church wrapped up, he invited a special guest to stand and speak.

A fellow Haitian with glossy business cards, the woman introduced herself as a consultant who’d driven in from Dayton. She could help anyone find the right lawyer, she explained. Or fix their credit score.

“I can help you buy a house,” she said.

Fernande just listened. Two days earlier, she and Rocher had made another $1,400 mortgage payment. There was no cash left to save.

About this story

Lamy interpreted interviews from Haitian Creole while reporting in Springfield. Aaron Schaffer in Washington contributed to this report.Editing by Susan Levine. Photo editing by Natalia Jimenez. Design by Zachary Balcoff, Dwuan June and Carson TerBush. Design Editing by Christian Font. Audio production by Bishop Sand. Copy Editing by Jeff Cavallin and Courtney Rukan. Additional support by Kelley Benham French, KC Schaper, Ana Carano and Jordan Melendrez Dowd.

Source (Archive)