- Joined

- Sep 1, 2014

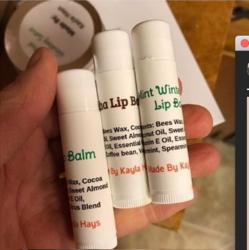

Once again, Anna proves her return to "veganism" only exists in service to her eating disorder. Both the lip balm and the "healing salve" contain beeswax.Anna is: getting freebies from actual CF patients; going for long car drives to hang on Earth Daddy; crying for animals; and wearing ugly clothes. Another day in the life of a NEET who refuses to grow up.

Some vegans make an exception for the consumption of bee products out of carefully considered respect for the role of bees in sustaining a fully plant-based lifestyle. But it is entirely possible that Anna is so dumb that she does not realize beeswax is an animal product.

Oh man, black walnuts. My parents' property came with black walnut trees, and even though they use them for many purposes, they say they'd cut them all down and replace them with butternuts if they could go back in time and do things over.

I was constantly getting in trouble for messing with them when I was a kid. My parents didn't want me dispersing the nuts to other parts of the yard, because once they take root, they're impossible to pull by hand and really difficult to dig out with a shovel. Also, they stain skin so badly that my mom didn't want me to look like a dirty kid at school.

Black walnut is safe to all livestock except horses, and horses are rarely harmed unless black walnut wood shavings are used as stall bedding. However, all parts of the black walnut tree produce a compound called juglone. This is not only passively released into the soil by fallen aerial parts and dead roots, but also actively excreted by the living root system as a sort of chemical attack. Many popular edible and ornamental plants cannot tolerate even a small concentration of juglone and will die within a few months if planted under a black walnut. Other walnut varieties are more friendly to surrounding plants, but these days, most commercially available walnut trees are grown on black walnut rootstock anyway.

Black walnuts themselves are perfectly edible, but they are a tremendous pain in the ass to process because the hulls fucking reek and both stink up and permanently stain anything they touch, the outer shells are thick and difficult to crack, and the sturdy inner shells curl around the nutmeats making them hard to dig out.

Here's how I'd suggest processing black walnuts. First, get a lot of them, because it is much more efficient to proceed with one big batch as opposed to fussing over many small ones. Discard any that appear moldy or where the hulls have broken down to look like coffee grounds. These are spoiled and are likely to spoil others, wasting your hard work. Make a wooden trough of any length, and one car tire wide. When the weather forecast is clear, put the nuts in the trough and drive your car over them to split the hulls. Then spread them out in a single layer on a tarp and let them sit in the sun until the surface of the hulls is dry. This will help a little with the mess, but you will still want to wear rubber gloves, possibly a bandana and safety goggles to shield your face, and clothes you don't care about as you hull the nuts. I use an oyster knife to make the process go faster, but my dad prefers a putty knife. Toss the hulled nuts in large buckets until they're a few layers deep, hose off the hulled nuts in their buckets, spread them out, and let them dry again, turning them a few times so they dry evenly. At this stage, they become incredibly attractive to squirrels, since you have done the nastiest part of the processing for them. A yapping dog comes in handy here. Once the hulled nuts are completely dry to the touch, put them in mesh bags and hang them someplace squirrels and rats won't get into. Let them cure for 2 or 3 weeks, periodically shaking them up a bit and making sure air circulates on all sides to prevent spoilage. After they are completely cured, it is easier to pick the nutmeats out of the shells, and you can pack them in bushel baskets or boxes without losing your hard-won harvest to mold.

Is all this trouble worth it? I'd say yes, but I hate myself and I do not value my time. In any case, black walnut meats have a richer flavor than English walnuts do, and when baked or toasted, they have a really lovely fragrance. If you only have access to English walnuts, you can buy natural or artificially-flavored culinary extracts to impart black walnut aromatics to whatever you're making. I suspect this is what Anna's friend is using in her salve; it doesn't have any known medicinal value, but it is easy to source online, easy to work with, and relatively inexpensive.

Actual medicinal extracts of black walnut hull appear to have antifungal properties when applied topically, and I've anecdotally noticed that prolonged contact with the straight juice will do away with warts. But if you are using enough of the natural hull extract to be effective, your remedy will permanently dye anything it touches. It's the juglone that's responsible for both the color and medicinal effect - you don't get one without the other. Your skin won't return to its normal hue until the outer layer is completely exfoliated. Even restricting yourself to natural cures, there are comparable treatments that are far less troublesome to prep and use.

That said, the hulls do make a lovely dye when you mean to dye things with them.

Here's a picture of a wool top made from yarn dyed with black walnut hulls. I've dyed other wool and cotton items for period-correct historical garments with uniformly great success. You don't need to use a mordant to make the dye fast on a protein fiber, and after you rinse it clear, the color will not transfer when it is washed with other fabrics. Depending on how long you leave your item in the dye pot, you can achieve a whole spectrum of attractive warm brown colors; modified with iron, you get lovely dark charcoal-ashy shades.

A big mistake I made with this project is putting the yarn directly in the pot with the dyestuff floating around loose. Picking all the little shreds of hull off the skeins prior to winding the yarn and knitting it up took longer than either spinning or knitting, and it was not any fun at all.

e: I was asked if items dyed with black walnut hulls end up being stinky, so I thought I'd mention that the heated dye bath does not smell as strongly as the green hulls do, and the clean rinsed garment doesn't retain any odor besides the textile's own characteristic smell. I suspect the stinky compounds denature and break down at high temperatures.

In conclusion, if you have access to a black walnut tree and want to try doing something practical with it, I'd recommend a dye project over eating the nuts. A stinky, stain-y home remedy is not worth the trouble.

I was constantly getting in trouble for messing with them when I was a kid. My parents didn't want me dispersing the nuts to other parts of the yard, because once they take root, they're impossible to pull by hand and really difficult to dig out with a shovel. Also, they stain skin so badly that my mom didn't want me to look like a dirty kid at school.

Black walnut is safe to all livestock except horses, and horses are rarely harmed unless black walnut wood shavings are used as stall bedding. However, all parts of the black walnut tree produce a compound called juglone. This is not only passively released into the soil by fallen aerial parts and dead roots, but also actively excreted by the living root system as a sort of chemical attack. Many popular edible and ornamental plants cannot tolerate even a small concentration of juglone and will die within a few months if planted under a black walnut. Other walnut varieties are more friendly to surrounding plants, but these days, most commercially available walnut trees are grown on black walnut rootstock anyway.

Black walnuts themselves are perfectly edible, but they are a tremendous pain in the ass to process because the hulls fucking reek and both stink up and permanently stain anything they touch, the outer shells are thick and difficult to crack, and the sturdy inner shells curl around the nutmeats making them hard to dig out.

Here's how I'd suggest processing black walnuts. First, get a lot of them, because it is much more efficient to proceed with one big batch as opposed to fussing over many small ones. Discard any that appear moldy or where the hulls have broken down to look like coffee grounds. These are spoiled and are likely to spoil others, wasting your hard work. Make a wooden trough of any length, and one car tire wide. When the weather forecast is clear, put the nuts in the trough and drive your car over them to split the hulls. Then spread them out in a single layer on a tarp and let them sit in the sun until the surface of the hulls is dry. This will help a little with the mess, but you will still want to wear rubber gloves, possibly a bandana and safety goggles to shield your face, and clothes you don't care about as you hull the nuts. I use an oyster knife to make the process go faster, but my dad prefers a putty knife. Toss the hulled nuts in large buckets until they're a few layers deep, hose off the hulled nuts in their buckets, spread them out, and let them dry again, turning them a few times so they dry evenly. At this stage, they become incredibly attractive to squirrels, since you have done the nastiest part of the processing for them. A yapping dog comes in handy here. Once the hulled nuts are completely dry to the touch, put them in mesh bags and hang them someplace squirrels and rats won't get into. Let them cure for 2 or 3 weeks, periodically shaking them up a bit and making sure air circulates on all sides to prevent spoilage. After they are completely cured, it is easier to pick the nutmeats out of the shells, and you can pack them in bushel baskets or boxes without losing your hard-won harvest to mold.

Is all this trouble worth it? I'd say yes, but I hate myself and I do not value my time. In any case, black walnut meats have a richer flavor than English walnuts do, and when baked or toasted, they have a really lovely fragrance. If you only have access to English walnuts, you can buy natural or artificially-flavored culinary extracts to impart black walnut aromatics to whatever you're making. I suspect this is what Anna's friend is using in her salve; it doesn't have any known medicinal value, but it is easy to source online, easy to work with, and relatively inexpensive.

Actual medicinal extracts of black walnut hull appear to have antifungal properties when applied topically, and I've anecdotally noticed that prolonged contact with the straight juice will do away with warts. But if you are using enough of the natural hull extract to be effective, your remedy will permanently dye anything it touches. It's the juglone that's responsible for both the color and medicinal effect - you don't get one without the other. Your skin won't return to its normal hue until the outer layer is completely exfoliated. Even restricting yourself to natural cures, there are comparable treatments that are far less troublesome to prep and use.

That said, the hulls do make a lovely dye when you mean to dye things with them.

Here's a picture of a wool top made from yarn dyed with black walnut hulls. I've dyed other wool and cotton items for period-correct historical garments with uniformly great success. You don't need to use a mordant to make the dye fast on a protein fiber, and after you rinse it clear, the color will not transfer when it is washed with other fabrics. Depending on how long you leave your item in the dye pot, you can achieve a whole spectrum of attractive warm brown colors; modified with iron, you get lovely dark charcoal-ashy shades.

A big mistake I made with this project is putting the yarn directly in the pot with the dyestuff floating around loose. Picking all the little shreds of hull off the skeins prior to winding the yarn and knitting it up took longer than either spinning or knitting, and it was not any fun at all.

e: I was asked if items dyed with black walnut hulls end up being stinky, so I thought I'd mention that the heated dye bath does not smell as strongly as the green hulls do, and the clean rinsed garment doesn't retain any odor besides the textile's own characteristic smell. I suspect the stinky compounds denature and break down at high temperatures.

In conclusion, if you have access to a black walnut tree and want to try doing something practical with it, I'd recommend a dye project over eating the nuts. A stinky, stain-y home remedy is not worth the trouble.

Last edited: