Let's pretend for one moment that he does die before the election, just for the funsies. What happens then? Will the nomination revert to option number 2, aka Bernie Sanders? Or will his running mate automatically replace him just the way Vice-President is supposted to step in after the Big Man in the White House chokes on a piece of matzo? Does he even have a running mate yet?

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

US Joe Biden News Megathread - The Other Biden Derangement Syndrome Thread (with a side order of Fauci Derangement Syndrome)

- Thread starter Borscht

- Start date

Honka Honka Burning Love

In Clown World, the only god is the one who Honks.

True & Honest Fan

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Aug 29, 2019

Yes and no, Socialism is a very broad term with many different things in it's umbrella (Communism is a subset of Socialism)Socialism is now nothing more than a buzzword for corporate globalist types who are successfully wiping out the most anti-corporation political movement possible. It's amazing that a whole political ideology is now little more than a sock puppet for its greatest enemies.

The Left very much want the "We get to tell you what to make" part of Socialism, and to "Tax the profits" but are 100% willing to give Tax breaks if the Companies give to the "Right" NGOs..who give back to the Left.

It manages to be even more vile than Communism really, at least under Communism you have to be breaking the rules to be corrupt, You just straight up lie and steal.

The System they are trying to build is a dirty ass "Public Private Partnership" where they will legally launder money from the Consumers and the Taxpayers into their own pockets in a way that will be entirely legal..and entirely impossible to actually find out what is going on.

Edit : TDLR Gas the NGOs.

legalkochi

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Dec 17, 2019

She's a DINO

Ha, I wish she was a DINO when it came to guns, but no, she's very pro gun control.

My dislike of Kamala Harris grew even further when she made the decision to request the Ninth Circuit to do an en banc hearing of Peruta v. San Diego County just because she didn't like the way the panel of three judges voted to make the "good cause" requirement in order to get a concealed carry permit unconstitutional. As a result of her actions, the "good cause" requirement was reinstated.

There's a lot of things about Kamala I don't like, but I especially don't like her stance and actions on the 2nd Amendment.

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2019

I'm not sure, I haven't read it, I've just skimmed the top of the Wikipedia page which has this quote: "The character was seen by many readers as a ground-breaking humanistic portrayal of an African-American slave, one who uses nonresistance and gives his life to protect others who have escaped from slavery."

"Uncle Tom, the title character, was initially seen as a noble, long-suffering Christian slave. In more recent years, however, his name has become an epithet directed towards African-Americans who are accused of selling out to whites. Stowe intended Tom to be a "noble hero" and praiseworthy person. Throughout the book, far from allowing himself to be exploited, Tom stands up for his beliefs and is grudgingly admired even by his enemies."

"Legree begins to hate Tom when Tom refuses Legree's order to whip his fellow slave."

I read it. It's free on Gutenberg.

Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Free kindle book and epub digitized and proofread by Project Gutenberg.

Basically, the story is this:

There are two subplots. The first is of Uncle Tom, an overseer of a slave master. This is within the first couple of chapters. This book has 45 chapters in it. Uncle Tom then gets sold off to another slaveowner and befriends his white daughter. The daughter and the slave owner (who hated blacks but was against slavery) die, and his wife sold him off to a vicious slave owner named Legree as opposed to giving him his freedom. He refuses to tell Legree where some slaves who ran away are, and Legree decided to get his own overseers, Sambo and Quimbo, to kill Uncle Tom. Before he dies, Uncle Tom successfully converts Sambo and Quimbo (and I think Legree) into Christianity.

There's also the subplot of a mulatto(?) woman who runs away with her son after realizing that he would be sold off with Uncle Tom. She has some dealings with a slave hunter before finding relatives with the Legrees (the relatives Uncle Tom refused to expose). They all end up going to Liberia in the end.

It's an anti-slavery novel. It's also pro-Christianity. Why people use "Uncle Tom" as an insult is beyond me. The rumor is that white people used it in the early 1900s as a negative, but there's no basis for that. And even if that were true, it makes those people throwing that insult around act live slave owners.

The same goes for the word "coon". "Coon" basically means "black person". It's in the same vein as calling someone a nigger. Why people use it as an insult also is beyond me too.

- Joined

- Sep 27, 2018

I imagine there's two kinds of people that unironically use 'Uncle Tom' as a pejorative. The first and vast majority just parrot it as a synonym for 'house Negro' since that's what that term has degraded to and don't actually know what the book or character are about. The second probably view his nonviolent resistance as patronizing and still think he's a traitor because if you're not actively committing violence against your 'oppressors' you might as well be so the degraded meaning still serves them.I don't get the usage of "Uncle Tom" as an insult for black people who side with white people because Uncle Tom died to protect people who escaped slavery.

That's as backwards as calling someone who hates Jews "Oskar Schindler", surely? Both of them were pretending to serve their bosses while trying to help as many people as they could, right?

Or maybe I'm just an idiot, feel free to correct me, but don't be mean about it.

- Joined

- Oct 21, 2018

most normal people understand that they are losing the plot.I'm not sure if you observed this phenomenon but people just whole sale absorb what the media feeds them.

It's not that they are dumb (some of these folks are very intelligent) I just dont think many folks are capable of understanding various ideas and issues on a large impersonal abstract scale that American society regularly deals with.

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2019

Just going to put this here for anyone interested.

www.macleans.ca

www.macleans.ca

Kamala Harris's father is slamming her for making a 'travesty' of her Jamaican heritage - Macleans.ca

Allen Abel: Donald Harris's rebuke over 'pot-smoking joy seeker' stereotype is one thing the Democratic presidential contender is disinclined to talk about. Another is her time in Canada.

- Joined

- Jun 4, 2019

She fucked Trudeau's wife, didn't she

pull over dat ass too fat

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2019

You're referring to liberals, which are completely distinct from "the left." Socialism also doesn't "tax profits" because socialism doesn't have profit. If you have private companies & profit, you've already failed.The Left very much want the "We get to tell you what to make" part of Socialism, and to "Tax the profits" but are 100% willing to give Tax breaks if the Companies give to the "Right" NGOs..who give back to the Left.

And communism isn't a subset of socialism. There is a very specific form of socialism that's meant to pursue the eventual goal of communism (e.g. Marxism-Leninism) but this is distinct from communism by definition. A communist might advocate for such a system, but the system itself isn't communism, it's just a form of socialism.

But the vast majority of Americans who throw around the word "socialism" have no idea what socialism is, and just equate it to mean "any form of public program." I think this probably started as a red scare thing, but it backfired once the cold war stopped having relevance on everyday people. I find it funny, because now you get a bunch of liberals who think "wait, I want such-and-such publicly funded program, I must be a socialist!" lmao

- Joined

- Jul 8, 2020

When I saw that this was published by Maclean's, my jaw dropped a bit because it's a huge lefty rag up in Canada. Then I noticed that it was published back in Feb 2019 and it made a bit more sense. I archived it in the (likely) chance they memoryhole it.Just going to put this here for anyone interested.

Kamala Harris's father is slamming her for making a 'travesty' of her Jamaican heritage - Macleans.ca

Allen Abel: Donald Harris's rebuke over 'pot-smoking joy seeker' stereotype is one thing the Democratic presidential contender is disinclined to talk about. Another is her time in Canada.www.macleans.ca

View attachment 1516005

Archive of article "Kamala Harris's father is slamming her for making a 'travesty' of her Jamaican heritage"

- Joined

- Sep 26, 2014

RIP innocent Ugandan wrestler who didn't die for this shit.

- Joined

- Oct 1, 2018

So either Harris was picked as the VP candidate very late, or MSNBC got the speaking schedule quite a while ago

Honka Honka Burning Love

In Clown World, the only god is the one who Honks.

True & Honest Fan

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Aug 29, 2019

And this is why people are confused. The terms don't actually mean anything anymore because The Totalitarians co-opt every term they can to pozz it because being able to discuss ideas and politics in a clear manner makes it harder for them to hide.You're referring to liberals, which are completely distinct from "the left.

That is false, look up "Market Socialism"You're referring to liberals, which are completely distinct from "the left." Socialism also doesn't "tax profits" because socialism doesn't have profit. If you have private companies & profit, you've already failed.

As I said, Socialism an extraordinarily wide term.

And communism isn't a subset of socialism. There's a very specific form of socialism that's meant to pursue the eventual goal of communism (e.g. Marxist-Leninism) but this is distinct from communism by definition. A communist might advocate for such a system, but the system itself isn't communism, isn't just a form of socialism.

Communism is the Endpoint Goal of all Socialist States, The problem is The People in charge never want to give up their money and power and comforts. This is why people can claim "NO REAL COMMUNISM tm" because technically they are correct..no Communist country has ever truly existed..it is always the attempt to reach it that ends in Millions dead every damn time. The only real difference between the Ideologies is that "Communists" say they are going to give up power once "Equality" has been achieved..Socialists just say fuck off the power is mine.

But the vast majority of Americans who throw around the word "socialism" have no idea what socialism is, and just equate it to mean "any form of public program." I think this probably started as a red scare thing, but it backfired once the cold war stopped having relevance on everyday people. I find it funny, because now you get a bunch of liberals who think "wait, I want such-and-such publicly funded program, I must be a socialist!" lmao

The vast majority of Americans don't know what any of it means, most of them don't even know what their own political principles actually are.

pull over dat ass too fat

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2019

I wouldn't say they co-opted it as much as they were prescribed as it. Any time some Democrat comes up with a welfare system paid for by working class people, you can count on the media to screech about how it's "socialism." Of course it's not socialism, because it's by definition the exact opposite of socialism. There are actual leftists in the US. There have been for decades, in fact. But what you were describing is not "the left."And this is why people are confused. The terms don't actually mean anything anymore because The Totalitarians co-opt every term they can to pozz it because being able to discuss ideas and politics in a clear manner makes it harder for them to hide.

That's not private companies taking profit. It's also entirely different from the ideas you were previously suggesting (which again, is just liberalism).That is false, look up "Market Socialism"

As I said, Socialism an extraordinarily wide term.

This is factually and provably wrong, but I think I've already argued about this with you before. Socialism predates the ideas of communism. Read more, I'm not gonna waste more time going down this rabbit hole again.Communism is the Endpoint Goal of all Socialist States

- Joined

- Jul 25, 2016

AOC isn't speaking? Is this a snub?So either Harris was picked as the VP candidate very late, or MSNBC got the speaking schedule quite a while ago

View attachment 1516039

Last edited:

- Joined

- Jan 23, 2015

Say it as often as you like, that's literally not what he said you cock-chugging retard. I realize that your entire candidacy was launched on and depends on this lie being true, but it ain't. He explicitly condemned the Nazis and the White Nationalists, but God forbid we go two seconds without having an intern lie for you.

- Joined

- May 24, 2019

What did he say then? I've only seen the media reporting the "fine people" line.View attachment 1516113

Say it as often as you like, that's literally not what he said you cock-chugging retard. I realize that your entire candidacy was launched on and depends on this lie being true, but it ain't. He explicitly condemned the Nazis and the White Nationalists, but God forbid we go two seconds without having an intern lie for you.

- Joined

- Jan 23, 2015

What did he say then? I've only seen the media reporting the "fine people" line.

1:55 "And I'm not talking about the Neo Nazis or the White Nationalists, because they should be condemned totally."

The full context of what he said during that presser completely changes what they keep quoting him as saying, but they're all absolute fucking hacks who can't make a valid point to save their lives, so they just lie out of their asses. The "very fine people" narrative has been an absolute hoax before it even started. They lied about it right out of the gate. It was never true.

He didn't make retraction later, he didn't walk anything back, he didn't make any correction, he called those two groups pieces of shit right before talking about "very fine people on both sides" and the media snipped that part off and ran straight to the front pages. Joe Biden's entire campaign is founded on an overt lie.

- Joined

- Jun 14, 2018

You presume that socialism is anti-corporation, but it isn't. It just makes the government a corporation unto itself, as seen in every nation that adopted socialism.Socialism is now nothing more than a buzzword for corporate globalist types who are successfully wiping out the most anti-corporation political movement possible. It's amazing that a whole political ideology is now little more than a sock puppet for its greatest enemies.

- Joined

- May 16, 2019

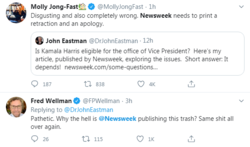

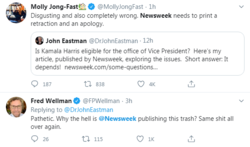

Apparently we're getting "birtherism" again.

Article in question: https://www.newsweek.com/some-questions-kamala-harris-about-eligibility-opinion-1524483 (archive)

It's not very interesting or persuasive, basically hinges on the question of whether the "birth on the soil no matter the circumstances" SCOTUS rulings applied to Harris, who was born a few years before they were in place. Relevant section:

Newsweek is getting crucified by checkmarks for allowing it.

Article in question: https://www.newsweek.com/some-questions-kamala-harris-about-eligibility-opinion-1524483 (archive)

It's not very interesting or persuasive, basically hinges on the question of whether the "birth on the soil no matter the circumstances" SCOTUS rulings applied to Harris, who was born a few years before they were in place. Relevant section:

Granted, our government's view of the Constitution's citizenship mandate has morphed over the decades to what is now an absolute "birth on the soil no matter the circumstances" view—but that morphing does not appear to have begun until the late 1960s, after Kamala Harris' birth in 1964. The children born on U.S. soil to guest workers from Mexico during the Roaring 1920s were not viewed as citizens, for example, when, in the wake of the Great Depression, their families were repatriated to Mexico. Nor were the children born on U.S. soil to guest workers in the bracero program of the 1950s and early 1960s deemed citizens when that program ended, and their families emigrated back to their home countries.

So before we so cavalierly accept Senator Harris' eligibility for the office of vice president, we should ask her a few questions about the status of her parents at the time of her birth.

Were Harris' parents lawful permanent residents at the time of her birth? If so, then under the actual holding of Wong Kim Ark, she should be deemed a citizen at birth—that is, a natural-born citizen—and hence eligible. Or were they instead, as seems to be the case, merely temporary visitors, perhaps on student visas issued pursuant to Section 101(15)(F) of Title I of the 1952 Immigration Act? If the latter were indeed the case, then derivatively from her parents, Harris was not subject to the complete jurisdiction of the United States at birth, but instead owed her allegiance to a foreign power or powers—Jamaica, in the case of her father, and India, in the case of her mother—and was therefore not entitled to birthright citizenship under the 14th Amendment as originally understood.

Newsweek is getting crucified by checkmarks for allowing it.

- Joined

- Dec 16, 2019

This one (the fine people hoax) for whatever reason REALLY pisses of dilbert merchant.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.