Europe’s Defenses Risk Faltering Within Weeks Without US Support

Bloomberg (archive.ph)

By Andrea Palasciano, Alberto Nardelli, Natalia Ojewska, and William Wilkes

2025-03-06 19:43:20GMT

Lines of anti-tank defences at the first built part of the East Shield defense project on Poland's Russian border in Dabrowka.Photographer: Damian Lemański/Bloomberg

A few weeks after Donald Trump’s re-election to the White House, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk traveled to the marshy forests near the border with Russia to showcase one of Europe’s most ambitious defense projects.

The first section of the country’s $2.5 billion East Shield — an 800-kilometer (500-mile) stretch of fences, concrete barricades and anti-tank moats — was completed in late November, and Tusk wanted to show that Poland was doing its part to secure the continent from potential aggression from the Kremlin.

“This is an investment in peace,” the former European Council president, who oversaw the bloc’s summits for five years until 2019, said in late November in Dabrowka — a village near Russia’s Kaliningrad.

But the unspoken message of the fortifications — an updated version of France’s Maginot Line, which ultimately failed to hold back Nazi Germany — is that Europe is vulnerable, and it knows it.

Lacking troops, air defenses and ammunition, the continent’s front-line defenses are only equipped to repel an invasion from Russia for weeks at best without the US, according to defense officials, who asked not to be identified discussing sensitive information. Even if a complete American withdrawal is seen as extremely remote, a reduced US presence would also have an impact.

Tusk during a visit to the first built part of the East Shield in Dabrowka on Poland's border with Russia in November.Photographer: Damian Lemański/Bloomberg

Within NATO, Europe is reliant on the US for communications, intelligence and logistics as well as strategic military leadership and firepower. Contingency planning is ongoing for the unlikely scenario in which the US does turn its back on the alliance and pulls all troops out of Europe.

The continent largely disarmed after the Cold War and saw Russia as a basket case and then a trading partner. Even after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Europe’s leaders struggled to pivot. It’s only in recent years that Europe’s NATO members have come to terms with the threat posed by Moscow.

Trump’s return to the White House has heightened Europe’s alarm. The US president has shown little concern about Russian aggression and has decided to halt US arms supplies to Ukraine, stopped providing some intelligence to Kyiv’s forces and rejected American troops taking part in a mission to keep a peace deal he’s seeking to broker with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The continent has responded with a show of solidarity and a massive wave of cash. The European Union plans to extend €150 billion ($160 billion) in loans and allow member states to spend an additional €650 billion on defense. The UK plans to shift development aid to its military, and Germany intends to break with tradition by loosening constitutional borrowing restrictions to rearm.

On Thursday, the EU also agreed to begin discussions on a long-term reform of its fiscal rules to allow member states to spend more on defense, following a push from Berlin.

Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskiy with European Council President Antonio Costa and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen on arrival at a special European Council meeting, in Brussels on March 6.Photographer: Simon Wohlfahrt/Bloomberg

The whole effort is expected to eventually need hundreds of billions of euros more. But after years of underinvestment and decades of reliance on the US, more than money is required to shore up Europe’s security. Replacing the array of support that the US provides — from logistics and intelligence to weapons systems — could take more than five years, the people said.

Precise data on Europe’s capabilities and stockpiles are closely held. But behind the scenes, defense officials warn that in extreme scenarios the region’s inventories of aircraft missiles could quickly start to run short without the US, according to some estimates. Ammunition may run low within days and air defenses would be unable to provide sufficient cover for ground operations.

Despite three years of war in Europe, the continent still lacks basics like sufficient production capacity for gunpowder. That means gearing up mainly involves buying from the US.

British army soldiers prepare a Lightweight Multi-Role (LMM) missile system during the a NATO training exercise in Smardan, Romania, on Feb. 19.Photographer: Andrei Pungovschi/Bloomberg

Poland, which has the highest defense-spending rate in Europe, is among the region’s largest buyers of American military equipment, with $60 billion in orders, including Apache helicopters, Abrams tanks and F-35 fighter jets — some of which aren’t scheduled to be delivered until next decade. But in the event of a full-blown war, plans would likely also include converting industry to produce ammunition and other weapons.

The lack of as many as 100,000 combat personnel and technicians capable of engaging in high-tech modern warfare is a deficiency that’s especially hard for an aging continent to address. Social tensions also need to be managed if spending is seen as eating into pensions and welfare programs.

Germany, the EU’s most populous country and biggest economy, had a little over 181,000 troops at the end of 2024, a slight decrease from the previous year at a time when increases are needed. While recruitment has intensified, it wasn’t enough to compensate for soldiers leaving service or retiring.

That puts pressure on France and the UK, which have nuclear weapons, to provide a deterrence. French President Emmanuel Macron said on Wednesday that he’s prepared to enter talks to use the country’s nuclear capabilities to defend European allies.

Alongside Britain’s Keir Starmer, the French president has become a key voice for Europe and has long urged allies to take more control over the continent’s security. In a landmark speech a few months into his first term in 2017, he advocated for a joint intervention force and a common defense budget, but failed to rally partners into action — often getting rebuffed by Germany.

Zelenskiy, from left, Starmer and Macron at a meeting during a summit in London on March 2.Photographer: Justin Tallis/AFP/Bloomberg

“We are vitally bound to the US, there is no question about that,” Lithuanian Foreign Minister Kestutis Budrys told reporters on Monday. “It is a fairly simple and easy way to deter Russia, to avoid bigger problems.”

The Baltic nation — a potential Kremlin target alongside Latvia, Estonia, Romania and Poland — has been seeking to lobby for more American troops on top of the existing 1,000 already stationed there, a sign of Europe’s enduring reliance on the US despite Trump’s rhetoric.

Europe would struggle to manage a defensive operation on its own. The US operates 17 sophisticated spy planes — packed with equipment to detect enemy radio, radar and communications — while the UK only has three.

Other European countries currently only operate smaller twin-engine reconnaissance planes, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies. Germany has ordered three new surveillance planes from Canada’s Bombardier Inc., but they won’t be in the air until 2028.

The dire situation has tied Europe and Ukraine together like never before. With US support in doubt, Kyiv is especially dependent on military and financial aid from Europe. On the flipside, Ukraine has the largest army and hard-won expertise in drone warfare that its allies lack.

Europe’s security weakness has been decades in the making. After the fall of the Iron Curtain and NATO’s expansion to the east in the 1990s, most countries embraced the opportunity to cut military budgets.

Over the past 30 years, core European NATO members have reduced the number of active troops by nearly 50%. In addition to combat-ready personnel, the shortages extend to the brain trust of senior officers, planners and strategists.

Spread out over more than two dozen countries from Greece to Iceland, the continent’s NATO members have about 1.5 million active military personnel, according to data from IISS. By comparison, Ukraine alone has 730,000.

Ukrainian cadets conduct training with American Colt M16A4 assault rifles in Kyiv region.Photographer: Olga Ivashchenko/Bloomberg

Local obligations and social resistance further limit the prospect for redeploying national armies to a peacekeeping mission in Ukraine on a large scale. After an emergency summit in London last weekend, Italy’s Premier Giorgia Meloni said sending Italian troops to Ukraine had “never been on the agenda.” Other leaders expressed similar sentiment.

“When peace eventually comes, the front line in Ukraine will be unbelievably long,” Denmark’s Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said. “The idea that there will be a single line with European soldiers guarding every centimeter is simply not realistic.”

European officials estimate that at least 30,000 soldiers would be needed to monitor a peace deal in Ukraine, but that would be difficult to muster and instead the prospective contingent would be little more than tripwire for Russia, the people said.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the rapid movement of troops and equipment played a crucial role in Kyiv’s ability to mount a defense. A similar ability to deploy forces quickly would be critical if European nations were faced with a Russian attack.

Belgian tanks during a NATO training exercise in February.Photographer: Andrei Pungovschi/Bloomberg

The European Court of Auditors warned last month that logistical obstacles could bog down defensive efforts because of a lack of centralized oversight. Moving tanks from one member state to another would encounter national weight regulations and might need to take long detours because of rickety bridges, according to a report.

The Baltics are particularly vulnerable to supply issues. Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia still use Soviet gauge rails, which means European trains can only get as far as the border with Poland. That makes sea lanes critical for delivering equipment and reinforcements in the event of an attack, but resources aren’t yet in place.

Both publicly and privately, the Trump administration has expressed commitment to NATO and a full exit is viewed by European officials as extremely remote. Matthew Whitaker, the US’s nominee for NATO ambassador, said during confirmation hearings this week that the US president remains committed to the alliance and sees his role as pushing allies to increase their share of defense spending.

Instead, Trump is widely expected to reduce the number of troops in Europe by over 20% and rein in contributions, the people said. The first move would likely be the withdrawal of the additional 20,000 soldiers that Joe Biden deployed after the start of Russia’s invasion three years ago.

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte with US Secretary of Defence Pete Hegseth during the NATO defence ministers' meeting, in Brussels on Feb. 13.Photographer: Omar Havana/Getty Images

The alliance is prepared for a recalibration of US forces away from Europe, Giuseppe Cavo Dragone, who took over as the chair of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s Military Committee last month, told Bloomberg.

“There is a kind of imbalance, so we need to re-balance,” the admiral said, calling the notion that Europe isn’t able to defend itself “blasphemy.”

Given the Trump administration’s skeptical stance toward Europe, NATO’s strategy is to keep the US at the table, even if it’s in a reduced capacity. Secretary General Mark Rutte is seen as a key figure to keep the transatlantic alliance together.

The former Dutch premier, who famously smoothed over an explosive NATO summit with Trump in 2018, has engaged in intense diplomacy, including several calls with the US president since his inauguration in January and visiting him at his residence in Mar-a-Lago.

Back at the Polish border with Russia, officials have learned lessons from history and are closely coordinating with Baltic neighbors to gird against Russia going around the fortifications, which will also include sensors and air-defense systems to secure against weapons that fly over a fence.

A Polish armored vehicle at the East Shield defense project on Poland's Russian border.Photographer: Damian Lemański/Bloomberg

Finland and the UK are also involved, as they would be called upon for logistics support in the event of an attack, which Europe increasingly sees as a question of when and not if.

“Russia will be probably able to recreate its military capabilities in a relatively short time,” said Poland’s Deputy Defense Minister Cezary Tomczyk said in an interview in Warsaw. “Within three years, it can once again become a real threat to the world.”

— With assistance from Andra Timu, Milda Seputyte, Julia Janicki, Thomas Gualtieri, Slav Okov, Jan Bratanic, James Regan, and Andrea Dudik

(Updates with EU leaders decision in 10th paragraph. The previous version of the story corrected Donald Tusk’s official title in the first paragraph)

Bloomberg (archive.ph)

By Andrea Palasciano, Alberto Nardelli, Natalia Ojewska, and William Wilkes

2025-03-06 19:43:20GMT

Lines of anti-tank defences at the first built part of the East Shield defense project on Poland's Russian border in Dabrowka.Photographer: Damian Lemański/Bloomberg

A few weeks after Donald Trump’s re-election to the White House, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk traveled to the marshy forests near the border with Russia to showcase one of Europe’s most ambitious defense projects.

The first section of the country’s $2.5 billion East Shield — an 800-kilometer (500-mile) stretch of fences, concrete barricades and anti-tank moats — was completed in late November, and Tusk wanted to show that Poland was doing its part to secure the continent from potential aggression from the Kremlin.

“This is an investment in peace,” the former European Council president, who oversaw the bloc’s summits for five years until 2019, said in late November in Dabrowka — a village near Russia’s Kaliningrad.

But the unspoken message of the fortifications — an updated version of France’s Maginot Line, which ultimately failed to hold back Nazi Germany — is that Europe is vulnerable, and it knows it.

Lacking troops, air defenses and ammunition, the continent’s front-line defenses are only equipped to repel an invasion from Russia for weeks at best without the US, according to defense officials, who asked not to be identified discussing sensitive information. Even if a complete American withdrawal is seen as extremely remote, a reduced US presence would also have an impact.

Tusk during a visit to the first built part of the East Shield in Dabrowka on Poland's border with Russia in November.Photographer: Damian Lemański/Bloomberg

Within NATO, Europe is reliant on the US for communications, intelligence and logistics as well as strategic military leadership and firepower. Contingency planning is ongoing for the unlikely scenario in which the US does turn its back on the alliance and pulls all troops out of Europe.

The continent largely disarmed after the Cold War and saw Russia as a basket case and then a trading partner. Even after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Europe’s leaders struggled to pivot. It’s only in recent years that Europe’s NATO members have come to terms with the threat posed by Moscow.

Trump’s return to the White House has heightened Europe’s alarm. The US president has shown little concern about Russian aggression and has decided to halt US arms supplies to Ukraine, stopped providing some intelligence to Kyiv’s forces and rejected American troops taking part in a mission to keep a peace deal he’s seeking to broker with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The continent has responded with a show of solidarity and a massive wave of cash. The European Union plans to extend €150 billion ($160 billion) in loans and allow member states to spend an additional €650 billion on defense. The UK plans to shift development aid to its military, and Germany intends to break with tradition by loosening constitutional borrowing restrictions to rearm.

On Thursday, the EU also agreed to begin discussions on a long-term reform of its fiscal rules to allow member states to spend more on defense, following a push from Berlin.

Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskiy with European Council President Antonio Costa and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen on arrival at a special European Council meeting, in Brussels on March 6.Photographer: Simon Wohlfahrt/Bloomberg

The whole effort is expected to eventually need hundreds of billions of euros more. But after years of underinvestment and decades of reliance on the US, more than money is required to shore up Europe’s security. Replacing the array of support that the US provides — from logistics and intelligence to weapons systems — could take more than five years, the people said.

Precise data on Europe’s capabilities and stockpiles are closely held. But behind the scenes, defense officials warn that in extreme scenarios the region’s inventories of aircraft missiles could quickly start to run short without the US, according to some estimates. Ammunition may run low within days and air defenses would be unable to provide sufficient cover for ground operations.

Despite three years of war in Europe, the continent still lacks basics like sufficient production capacity for gunpowder. That means gearing up mainly involves buying from the US.

British army soldiers prepare a Lightweight Multi-Role (LMM) missile system during the a NATO training exercise in Smardan, Romania, on Feb. 19.Photographer: Andrei Pungovschi/Bloomberg

Poland, which has the highest defense-spending rate in Europe, is among the region’s largest buyers of American military equipment, with $60 billion in orders, including Apache helicopters, Abrams tanks and F-35 fighter jets — some of which aren’t scheduled to be delivered until next decade. But in the event of a full-blown war, plans would likely also include converting industry to produce ammunition and other weapons.

The lack of as many as 100,000 combat personnel and technicians capable of engaging in high-tech modern warfare is a deficiency that’s especially hard for an aging continent to address. Social tensions also need to be managed if spending is seen as eating into pensions and welfare programs.

Germany, the EU’s most populous country and biggest economy, had a little over 181,000 troops at the end of 2024, a slight decrease from the previous year at a time when increases are needed. While recruitment has intensified, it wasn’t enough to compensate for soldiers leaving service or retiring.

That puts pressure on France and the UK, which have nuclear weapons, to provide a deterrence. French President Emmanuel Macron said on Wednesday that he’s prepared to enter talks to use the country’s nuclear capabilities to defend European allies.

Alongside Britain’s Keir Starmer, the French president has become a key voice for Europe and has long urged allies to take more control over the continent’s security. In a landmark speech a few months into his first term in 2017, he advocated for a joint intervention force and a common defense budget, but failed to rally partners into action — often getting rebuffed by Germany.

Zelenskiy, from left, Starmer and Macron at a meeting during a summit in London on March 2.Photographer: Justin Tallis/AFP/Bloomberg

“We are vitally bound to the US, there is no question about that,” Lithuanian Foreign Minister Kestutis Budrys told reporters on Monday. “It is a fairly simple and easy way to deter Russia, to avoid bigger problems.”

The Baltic nation — a potential Kremlin target alongside Latvia, Estonia, Romania and Poland — has been seeking to lobby for more American troops on top of the existing 1,000 already stationed there, a sign of Europe’s enduring reliance on the US despite Trump’s rhetoric.

Europe would struggle to manage a defensive operation on its own. The US operates 17 sophisticated spy planes — packed with equipment to detect enemy radio, radar and communications — while the UK only has three.

Other European countries currently only operate smaller twin-engine reconnaissance planes, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies. Germany has ordered three new surveillance planes from Canada’s Bombardier Inc., but they won’t be in the air until 2028.

The dire situation has tied Europe and Ukraine together like never before. With US support in doubt, Kyiv is especially dependent on military and financial aid from Europe. On the flipside, Ukraine has the largest army and hard-won expertise in drone warfare that its allies lack.

Europe’s security weakness has been decades in the making. After the fall of the Iron Curtain and NATO’s expansion to the east in the 1990s, most countries embraced the opportunity to cut military budgets.

Over the past 30 years, core European NATO members have reduced the number of active troops by nearly 50%. In addition to combat-ready personnel, the shortages extend to the brain trust of senior officers, planners and strategists.

Spread out over more than two dozen countries from Greece to Iceland, the continent’s NATO members have about 1.5 million active military personnel, according to data from IISS. By comparison, Ukraine alone has 730,000.

Ukrainian cadets conduct training with American Colt M16A4 assault rifles in Kyiv region.Photographer: Olga Ivashchenko/Bloomberg

Local obligations and social resistance further limit the prospect for redeploying national armies to a peacekeeping mission in Ukraine on a large scale. After an emergency summit in London last weekend, Italy’s Premier Giorgia Meloni said sending Italian troops to Ukraine had “never been on the agenda.” Other leaders expressed similar sentiment.

“When peace eventually comes, the front line in Ukraine will be unbelievably long,” Denmark’s Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said. “The idea that there will be a single line with European soldiers guarding every centimeter is simply not realistic.”

European officials estimate that at least 30,000 soldiers would be needed to monitor a peace deal in Ukraine, but that would be difficult to muster and instead the prospective contingent would be little more than tripwire for Russia, the people said.

What Our Analysts Say:

What Our Analysts Say:

“Europe could in theory step in to cover the financial gap left by the US. The problem is not one of magnitude. Rather, the biggest challenges would be taking decisions fast enough and replacing US support in key tactical areas.”

— Alex Kokcharov, Bloomberg Economics analyst; Alex Isakov, economist; and Antonio Barroso, analyst (Bloomberg subscribers can click here for the full report

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the rapid movement of troops and equipment played a crucial role in Kyiv’s ability to mount a defense. A similar ability to deploy forces quickly would be critical if European nations were faced with a Russian attack.

Belgian tanks during a NATO training exercise in February.Photographer: Andrei Pungovschi/Bloomberg

The European Court of Auditors warned last month that logistical obstacles could bog down defensive efforts because of a lack of centralized oversight. Moving tanks from one member state to another would encounter national weight regulations and might need to take long detours because of rickety bridges, according to a report.

The Baltics are particularly vulnerable to supply issues. Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia still use Soviet gauge rails, which means European trains can only get as far as the border with Poland. That makes sea lanes critical for delivering equipment and reinforcements in the event of an attack, but resources aren’t yet in place.

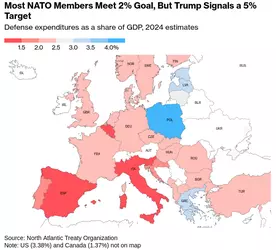

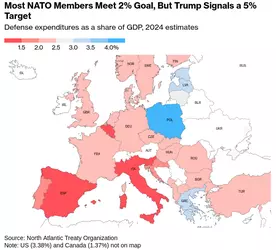

Both publicly and privately, the Trump administration has expressed commitment to NATO and a full exit is viewed by European officials as extremely remote. Matthew Whitaker, the US’s nominee for NATO ambassador, said during confirmation hearings this week that the US president remains committed to the alliance and sees his role as pushing allies to increase their share of defense spending.

Instead, Trump is widely expected to reduce the number of troops in Europe by over 20% and rein in contributions, the people said. The first move would likely be the withdrawal of the additional 20,000 soldiers that Joe Biden deployed after the start of Russia’s invasion three years ago.

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte with US Secretary of Defence Pete Hegseth during the NATO defence ministers' meeting, in Brussels on Feb. 13.Photographer: Omar Havana/Getty Images

The alliance is prepared for a recalibration of US forces away from Europe, Giuseppe Cavo Dragone, who took over as the chair of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s Military Committee last month, told Bloomberg.

“There is a kind of imbalance, so we need to re-balance,” the admiral said, calling the notion that Europe isn’t able to defend itself “blasphemy.”

Given the Trump administration’s skeptical stance toward Europe, NATO’s strategy is to keep the US at the table, even if it’s in a reduced capacity. Secretary General Mark Rutte is seen as a key figure to keep the transatlantic alliance together.

The former Dutch premier, who famously smoothed over an explosive NATO summit with Trump in 2018, has engaged in intense diplomacy, including several calls with the US president since his inauguration in January and visiting him at his residence in Mar-a-Lago.

Back at the Polish border with Russia, officials have learned lessons from history and are closely coordinating with Baltic neighbors to gird against Russia going around the fortifications, which will also include sensors and air-defense systems to secure against weapons that fly over a fence.

A Polish armored vehicle at the East Shield defense project on Poland's Russian border.Photographer: Damian Lemański/Bloomberg

Finland and the UK are also involved, as they would be called upon for logistics support in the event of an attack, which Europe increasingly sees as a question of when and not if.

“Russia will be probably able to recreate its military capabilities in a relatively short time,” said Poland’s Deputy Defense Minister Cezary Tomczyk said in an interview in Warsaw. “Within three years, it can once again become a real threat to the world.”

— With assistance from Andra Timu, Milda Seputyte, Julia Janicki, Thomas Gualtieri, Slav Okov, Jan Bratanic, James Regan, and Andrea Dudik

(Updates with EU leaders decision in 10th paragraph. The previous version of the story corrected Donald Tusk’s official title in the first paragraph)