Link (Archive)

Is quiche queer?

Until recently, I wouldn’t have known quite how to answer that question.

Sure, I remember the “Real Men Don’t Eat Quiche” book, which became a bestseller in the 1980s by satirizing stereotypes about masculinity. And as a Texan who grew up on barbecue and later came out as gay and even later as vegetarian — I’m now a tofu-and-potatoes man — I understand how, to some people, food choices can seem inextricable from sexual identity.

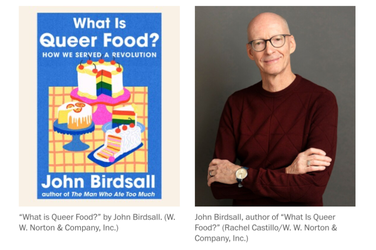

Is the food itself queer, though? Author John Birdsall has convinced me that it surely can be, that plenty of foods can be considered so through the meaning added from history, people and cultures. Among many other examples in his fascinating new book, “What is Queer Food?,” Birdsall breaks down the case for quiche, which appeared in ads in gay weekly newspapers for a brunch restaurant promising New York City’s “finest quiche Lorraine” in 1971 and more than a decade later was part of Phyllis Schlafly’s campaignagainst the Equal Rights Amendment. (She sent a quiche to 53 senators “as if to shame them … perhaps reminding the male senators of their masculinity.”)

In other words, queerness requires context. And in Birdsall’s lyrical account, food has become one of the languages that can express queer identity.

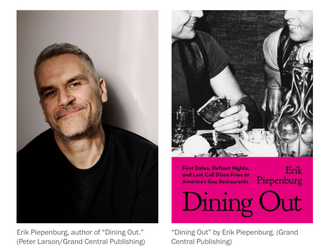

Birdsall’s work shares a publication date this week with another important book on a related topic, Erik Piepenburg’s “Dining Out,” an entertaining and moving cultural history of gay restaurants and the role they played in helping people find community and sex, fight oppression and even quite literally survive. At the start of Pride Month, in a year when the LGBTQ+ community (particularly the T) finds itself on the defensive amid attacks by Donald Trump’sadministration, the books present a one-two punch of historical lessons that food — whether eaten at home or in a restaurant — has been critical to the queer experience.

I read the books in tandem, and for an elder Gen X-er like me who came out in the early days of the AIDS epidemic, the cumulative effect was by turns sobering and hopeful, enlightening and infuriating, inspiring and melancholic. So I got Birdsall and Piepenburg on a Zoom call to talk about their books’ respective — and collective — missions and lessons. (A note on terminology: When picking an umbrella term for the community, Birdsall goes with “queer,” Piepenburg employs “gay,” and I use both, depending on which book I’m referencing.)

When I asked him about his book title’s question, Birdsall reminded me of James Baldwin’s point that blackness had little meaning except as it related to the construct of whiteness — and whiteness’s dominance. “Queer food only has meaning in the context of this repressive dominant culture that tried so hard to define homosexuality as deviance,” he said. “The foods that ultimately became queer for me were foods that pushed against that sort of dominant telling of what sexuality was.”

Example: In 1977, a group of gay men and lesbians in San Francisco formed a synagogue they named Sha’ar Zahav. During their first High Holy Days, the women said the prayers and the men cooked and served the traditional brisket, kugel and more. “To us, it seems pretty mild, but for that generation, who had grown up in really conservative, traditional patriarchal households, that was a revolutionary moment,” said Birdsall, whose previous book was “The Man Who Ate Too Much,” a biography of James Beard. “That queered food that, in another context, could have looked quite ordinary.”

Context matters when it comes to gay restaurants throughout history, too, Piepenburg said. Some restaurants might not be considered gay because they’re not owned or managed by gay people or don’t advertise themselves as such, but their identity can shift when enough gay people start patronizing them — even if only during certain hours.

“The concept of a space being ‘queered’ is relatively new, but we’ve been doing it for decades,” Piepenburg said. “If it’s the local diners where all the gay guys go at 2 a.m., or if it’s a lesbian consciousness-raising buffet, the food becomes queer because of who’s there and who’s eating it and when.”

The gay restaurant is just as important to the community’s history as the gay bar, Piepenburg says — perhaps even more so “because they can serve the community in ways the bar just can’t,” he said. People can more easily connect over more than alcohol and sex, and the spaces are often more inclusive than bars, with a more diverse clientele.

In some cases, gay customers went undetected — except to one another. At 1920s-era automats, where the pop of a coin and the turn of a knob opened the door to a dish, the communal tables in the middle of big cities were ripe for cruising by men and women alike. As Piepenburg writes, the automats opened by Horn & Hardart were rare early 20th-century restaurants that welcomed unescorted women, “making it easy for lesbian interaction.”

Restaurants such as Bloodroot in Connecticut have served as more than safe spaces; as lesbian feminist collectives, they hosted “women’s groups [who] met there to mobilize as much as to socialize,” Piepenburg writes.

In “Dining Out,” Piepenburg reserves particular affection for old-school diners, including the dearly departed (the Melrose in Chicago’s Boystown gayborhood) and the alive and kicking (Orphan Andy’s, which opened in 1977 in San Francisco’s Castro). “Restaurants in the American greasy spoon tradition have, for decades, been places where gay people of all shapes, orientations, and colors have made gay turf, often out of necessity when no other restaurant would serve our loud gay asses,” he writes.

Sometimes, though, rather than find another place to eat, these customers stood their ground and demanded change. Years before the Stonewall Inn uprising that has been called the beginning of the gay rights movement, restaurants were the site of protests large and small. Piepenburg writes about a 1965 sit-in that drew 150 protesters at a diner in Philadelphia after managers issued a rule to deny service to “homosexuals and persons wearing nonconforming clothing.” The protesters prevailed, and the policy changed.

I couldn’t help but think about the parallels to the Greensboro sit-ins at a Woolworth’s lunch counter that began five years earlier. I asked Piepenburg and Birdsall: Why have restaurants — rather than, say, movie theaters or grocery stores — so often been the site of civil rights protests, including by gay diners?

Piepenburg thinks about the 1983 lawsuit by two women against Papa Choux in Los Angeles, where they had gone for an anniversary dinner and were denied seating in a private curtained booth because those were reserved for mixed-gender couples. “The intimacy that that meal provided, or the promise of intimacy — to have that taken away from you in so public a way is one reason that restaurants have been that locus,” he said.

And then there are the etiquette strictures, as Birdsall points out. “Behavior in a restaurant, especially in a fine-dining restaurant, has been governed by so many invisible but very rigid rules of conduct,” he said.

Birdsall, who has worked as a restaurant chef, remembers going to Chez Panisse with a boyfriend in the early 1980s. “He reached for my hand on the table. I was terrified, but it also was completely thrilling. This was like our Stonewall,” he said. “I think it was shocking to some of the other diners, but we got a smile from our gay waiter.”

They might as well have been at Annie’s Paramount Steakhouse in D.C., which opened in 1948 and which the James Beard Foundation honored with an America’s Classic award in 2019 for its longtime embrace of the LGBTQ+ community. Its matriarch, Annie Kaylor, once approached two men she noticed were surreptitiously holding hands — and told them to feel free to show their affection on, rather than under, the table.

Perhaps that’s the biggest difference, at least historically, between dining out and dining in: Even the most welcoming restaurants couldn’t possibly provide the same level of comfort as private spaces could. Some of my favorite sections of Birdsall’s book focus on the parties, large and small, hosted by the likes of cookbook authors Richard Olney, Beard and New York Times food editor Craig Claiborne and attended by James Baldwin, Alice Waters, Paul Prudhomme, Diana Kennedy and more.

Birdsall describes Olney, half-naked as he welcomes guests to his outdoor lunch table under an arbor in France, as appearing “like some ancient lustful nature spirit.” Making his savory parmesan souffles, Birdsall writes, “is cooking as a process of stoking desire.” Claiborne, on the other hand, draws a hard line between his private (Fire Island) and public (Manhattan society) lives, and is truly himself only in the former — at least until he finally comes out in his 1982 memoir, “A Feast Made for Laughter.”

As evidence of the difference between food that’s closeted and food that’s unapologetically queer, Birdsall delights in juxtaposing salad recipes from Claiborne and Olney. The tomato and hearts of palm salad from “Craig Claiborne’s Favorites from the New York Times” in 1977? Birdsall calls it “a soppy platter of fanned-out slices sure to strike you as weirdly plastic, suffering from a kind of disassociation.” Olney’s “impromptu composed salad” from “Simple French Food” of 1974? It’s “a kinetic performance of pleasure” and “a staging of deviance.”

Then there’s “The Gay Cookbook,” a 1965 novelty work by Lou Rand whose (offensive) cover caricature depicts a toque-wearing cook handling a steak with literal limp-wristedness. Surely this is the definition of queer food, yes?

Well, maybe not. Rand’s book — with such recipes as “Swish Steak” — is a minstrel act, comic fodder for a straight audience. The award for gayest cookbook author would have to go to Beard, who by the 1960s was acclaimed as the Dean of American Cookery and who, as Birdsall writes, “was defying the unspoken prime directive of cookbooks, which is that women, exclusively, were bound to the domestic realm, the three squares a day of home life.”

Birdsall and Piepenburg get into so much more, including: the invention of the chiffon cake; the queer sensibilities of Edna Lewis’s Cafe Nicholson; the coded language in “The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook,” by Gertrude Stein’s longtime companion; and the original Hamburger Mary’s in San Francisco, where during the AIDS epidemic “a lot of people had their last meal in public,” as one longtime manager says in Piepenburg’s book.

The two authors comb through the past and unearth surprising connections. (Did you know that drag brunch has roots in AIDS activism and fundraising?)

But they also look forward. Birdsall’s prologue, dated 2022, pays homage to Lil’ Deb’s Oasis in Hudson, N.Y., where Birdsall and his husband have traveled to “find shelter from history,” he writes. “To spend an hour or two in what I want so badly to feel like queer utopia, a space from which enforcing ghouls of the brutal past find themselves permanently eighty-sixed.”

Piepenburg travels to the East Village, the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles, to Palm Springs and Fort Lauderdale, and looks at the gay restaurants of the present and future. At L.A.’s Ruby Fruit, he strikes up a conversation with a customer: Sarah Hymanson, chef-owner of the acclaimed restaurant Kismet. She’s friends with the Ruby Fruit owner, but other than that, why is she there?

“I eat at all different kinds of restaurants, but I’m always thinking about the way I’m supposed to behave in other spaces,” she tells Piepenburg. “In this one, I just feel at ease.”

Wherever there are storms, in other words, we all need shelter.

Quiche, drag brunch and sit-ins: How food informs queer identity

Is quiche queer?

Until recently, I wouldn’t have known quite how to answer that question.

Sure, I remember the “Real Men Don’t Eat Quiche” book, which became a bestseller in the 1980s by satirizing stereotypes about masculinity. And as a Texan who grew up on barbecue and later came out as gay and even later as vegetarian — I’m now a tofu-and-potatoes man — I understand how, to some people, food choices can seem inextricable from sexual identity.

Is the food itself queer, though? Author John Birdsall has convinced me that it surely can be, that plenty of foods can be considered so through the meaning added from history, people and cultures. Among many other examples in his fascinating new book, “What is Queer Food?,” Birdsall breaks down the case for quiche, which appeared in ads in gay weekly newspapers for a brunch restaurant promising New York City’s “finest quiche Lorraine” in 1971 and more than a decade later was part of Phyllis Schlafly’s campaignagainst the Equal Rights Amendment. (She sent a quiche to 53 senators “as if to shame them … perhaps reminding the male senators of their masculinity.”)

In other words, queerness requires context. And in Birdsall’s lyrical account, food has become one of the languages that can express queer identity.

Birdsall’s work shares a publication date this week with another important book on a related topic, Erik Piepenburg’s “Dining Out,” an entertaining and moving cultural history of gay restaurants and the role they played in helping people find community and sex, fight oppression and even quite literally survive. At the start of Pride Month, in a year when the LGBTQ+ community (particularly the T) finds itself on the defensive amid attacks by Donald Trump’sadministration, the books present a one-two punch of historical lessons that food — whether eaten at home or in a restaurant — has been critical to the queer experience.

I read the books in tandem, and for an elder Gen X-er like me who came out in the early days of the AIDS epidemic, the cumulative effect was by turns sobering and hopeful, enlightening and infuriating, inspiring and melancholic. So I got Birdsall and Piepenburg on a Zoom call to talk about their books’ respective — and collective — missions and lessons. (A note on terminology: When picking an umbrella term for the community, Birdsall goes with “queer,” Piepenburg employs “gay,” and I use both, depending on which book I’m referencing.)

When I asked him about his book title’s question, Birdsall reminded me of James Baldwin’s point that blackness had little meaning except as it related to the construct of whiteness — and whiteness’s dominance. “Queer food only has meaning in the context of this repressive dominant culture that tried so hard to define homosexuality as deviance,” he said. “The foods that ultimately became queer for me were foods that pushed against that sort of dominant telling of what sexuality was.”

Example: In 1977, a group of gay men and lesbians in San Francisco formed a synagogue they named Sha’ar Zahav. During their first High Holy Days, the women said the prayers and the men cooked and served the traditional brisket, kugel and more. “To us, it seems pretty mild, but for that generation, who had grown up in really conservative, traditional patriarchal households, that was a revolutionary moment,” said Birdsall, whose previous book was “The Man Who Ate Too Much,” a biography of James Beard. “That queered food that, in another context, could have looked quite ordinary.”

Context matters when it comes to gay restaurants throughout history, too, Piepenburg said. Some restaurants might not be considered gay because they’re not owned or managed by gay people or don’t advertise themselves as such, but their identity can shift when enough gay people start patronizing them — even if only during certain hours.

“The concept of a space being ‘queered’ is relatively new, but we’ve been doing it for decades,” Piepenburg said. “If it’s the local diners where all the gay guys go at 2 a.m., or if it’s a lesbian consciousness-raising buffet, the food becomes queer because of who’s there and who’s eating it and when.”

The gay restaurant is just as important to the community’s history as the gay bar, Piepenburg says — perhaps even more so “because they can serve the community in ways the bar just can’t,” he said. People can more easily connect over more than alcohol and sex, and the spaces are often more inclusive than bars, with a more diverse clientele.

In some cases, gay customers went undetected — except to one another. At 1920s-era automats, where the pop of a coin and the turn of a knob opened the door to a dish, the communal tables in the middle of big cities were ripe for cruising by men and women alike. As Piepenburg writes, the automats opened by Horn & Hardart were rare early 20th-century restaurants that welcomed unescorted women, “making it easy for lesbian interaction.”

Restaurants such as Bloodroot in Connecticut have served as more than safe spaces; as lesbian feminist collectives, they hosted “women’s groups [who] met there to mobilize as much as to socialize,” Piepenburg writes.

In “Dining Out,” Piepenburg reserves particular affection for old-school diners, including the dearly departed (the Melrose in Chicago’s Boystown gayborhood) and the alive and kicking (Orphan Andy’s, which opened in 1977 in San Francisco’s Castro). “Restaurants in the American greasy spoon tradition have, for decades, been places where gay people of all shapes, orientations, and colors have made gay turf, often out of necessity when no other restaurant would serve our loud gay asses,” he writes.

Sometimes, though, rather than find another place to eat, these customers stood their ground and demanded change. Years before the Stonewall Inn uprising that has been called the beginning of the gay rights movement, restaurants were the site of protests large and small. Piepenburg writes about a 1965 sit-in that drew 150 protesters at a diner in Philadelphia after managers issued a rule to deny service to “homosexuals and persons wearing nonconforming clothing.” The protesters prevailed, and the policy changed.

I couldn’t help but think about the parallels to the Greensboro sit-ins at a Woolworth’s lunch counter that began five years earlier. I asked Piepenburg and Birdsall: Why have restaurants — rather than, say, movie theaters or grocery stores — so often been the site of civil rights protests, including by gay diners?

Piepenburg thinks about the 1983 lawsuit by two women against Papa Choux in Los Angeles, where they had gone for an anniversary dinner and were denied seating in a private curtained booth because those were reserved for mixed-gender couples. “The intimacy that that meal provided, or the promise of intimacy — to have that taken away from you in so public a way is one reason that restaurants have been that locus,” he said.

And then there are the etiquette strictures, as Birdsall points out. “Behavior in a restaurant, especially in a fine-dining restaurant, has been governed by so many invisible but very rigid rules of conduct,” he said.

Birdsall, who has worked as a restaurant chef, remembers going to Chez Panisse with a boyfriend in the early 1980s. “He reached for my hand on the table. I was terrified, but it also was completely thrilling. This was like our Stonewall,” he said. “I think it was shocking to some of the other diners, but we got a smile from our gay waiter.”

They might as well have been at Annie’s Paramount Steakhouse in D.C., which opened in 1948 and which the James Beard Foundation honored with an America’s Classic award in 2019 for its longtime embrace of the LGBTQ+ community. Its matriarch, Annie Kaylor, once approached two men she noticed were surreptitiously holding hands — and told them to feel free to show their affection on, rather than under, the table.

Perhaps that’s the biggest difference, at least historically, between dining out and dining in: Even the most welcoming restaurants couldn’t possibly provide the same level of comfort as private spaces could. Some of my favorite sections of Birdsall’s book focus on the parties, large and small, hosted by the likes of cookbook authors Richard Olney, Beard and New York Times food editor Craig Claiborne and attended by James Baldwin, Alice Waters, Paul Prudhomme, Diana Kennedy and more.

Birdsall describes Olney, half-naked as he welcomes guests to his outdoor lunch table under an arbor in France, as appearing “like some ancient lustful nature spirit.” Making his savory parmesan souffles, Birdsall writes, “is cooking as a process of stoking desire.” Claiborne, on the other hand, draws a hard line between his private (Fire Island) and public (Manhattan society) lives, and is truly himself only in the former — at least until he finally comes out in his 1982 memoir, “A Feast Made for Laughter.”

As evidence of the difference between food that’s closeted and food that’s unapologetically queer, Birdsall delights in juxtaposing salad recipes from Claiborne and Olney. The tomato and hearts of palm salad from “Craig Claiborne’s Favorites from the New York Times” in 1977? Birdsall calls it “a soppy platter of fanned-out slices sure to strike you as weirdly plastic, suffering from a kind of disassociation.” Olney’s “impromptu composed salad” from “Simple French Food” of 1974? It’s “a kinetic performance of pleasure” and “a staging of deviance.”

Then there’s “The Gay Cookbook,” a 1965 novelty work by Lou Rand whose (offensive) cover caricature depicts a toque-wearing cook handling a steak with literal limp-wristedness. Surely this is the definition of queer food, yes?

Well, maybe not. Rand’s book — with such recipes as “Swish Steak” — is a minstrel act, comic fodder for a straight audience. The award for gayest cookbook author would have to go to Beard, who by the 1960s was acclaimed as the Dean of American Cookery and who, as Birdsall writes, “was defying the unspoken prime directive of cookbooks, which is that women, exclusively, were bound to the domestic realm, the three squares a day of home life.”

Birdsall and Piepenburg get into so much more, including: the invention of the chiffon cake; the queer sensibilities of Edna Lewis’s Cafe Nicholson; the coded language in “The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook,” by Gertrude Stein’s longtime companion; and the original Hamburger Mary’s in San Francisco, where during the AIDS epidemic “a lot of people had their last meal in public,” as one longtime manager says in Piepenburg’s book.

The two authors comb through the past and unearth surprising connections. (Did you know that drag brunch has roots in AIDS activism and fundraising?)

But they also look forward. Birdsall’s prologue, dated 2022, pays homage to Lil’ Deb’s Oasis in Hudson, N.Y., where Birdsall and his husband have traveled to “find shelter from history,” he writes. “To spend an hour or two in what I want so badly to feel like queer utopia, a space from which enforcing ghouls of the brutal past find themselves permanently eighty-sixed.”

Piepenburg travels to the East Village, the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles, to Palm Springs and Fort Lauderdale, and looks at the gay restaurants of the present and future. At L.A.’s Ruby Fruit, he strikes up a conversation with a customer: Sarah Hymanson, chef-owner of the acclaimed restaurant Kismet. She’s friends with the Ruby Fruit owner, but other than that, why is she there?

“I eat at all different kinds of restaurants, but I’m always thinking about the way I’m supposed to behave in other spaces,” she tells Piepenburg. “In this one, I just feel at ease.”

Wherever there are storms, in other words, we all need shelter.