L | A (Translated with ChatGPT)

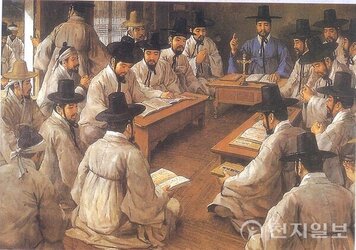

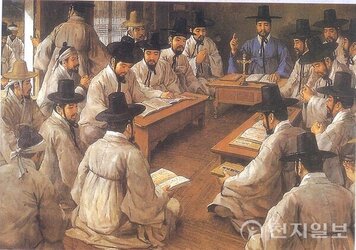

Kim Beom-woo's Interpreter’s House of Learning (Illustration by Professor Kim Tae, Myeongdong Cathedral Collection)

The Introduction of Western Studies

Seohak (Western Learning) refers to the combination of Western science and technology, along with Catholic faith, introduced from Qing China starting in the early 1600s after the Japanese invasions of Korea (Imjin War). The devastating experiences of the Imjin War and the Manchu invasions (Byeongja War) exposed the limitations of the Neo-Confucian system, ideology, and civilization in Joseon.

Before long, Joseon became a weakened society, unable to recognize external threats or protect its own people, even when aware of them.

Across society, movements arose to search for a new path for Joseon. Among these was a growing interest among intellectuals in foreign, particularly Western, knowledge and civilization. Some exceptional scholars began to turn their attention to the light coming from the broader world beyond the rigid ideological boundaries of Neo-Confucianism, which had become like a prison.

Seohak was not something spread by any particular person; rather, it was Western civilization that Joseon intellectuals, driven by curiosity and a thirst for knowledge, sought out and adopted themselves, as they were deeply interested in the principles of the universe and the nature of things.

Initially, Seohak referred to knowledge from the West, but it gradually expanded to include the Catholic faith. As Catholicism spread among the general populace, Seohak became increasingly synonymous with Catholic texts and knowledge.

Joseon envoys frequently interacted with Qing scholars in Beijing, collecting Chinese books, paintings, and various fascinating artifacts of civilization to bring back to Korea.

During these visits, they also encountered Western Catholic missionaries in Beijing, through whom they gained access to Western scientific books and instruments written in classical Chinese, as well as Catholic catechisms, which they brought back to Joseon.

The intellectuals of Joseon, a country known for its scholarly pursuits, had learned classical Chinese from a young age, so they had little difficulty reading Seohak texts (Western Learning books) written in Chinese. Their interest in reforming the reality of Joseon and their curiosity about foreign knowledge drove them to eagerly study these texts.

Among these intellectuals...

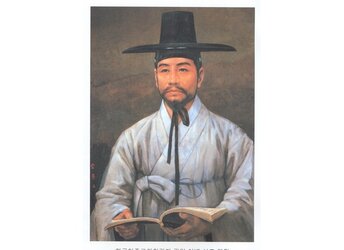

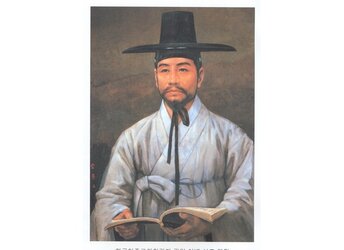

Yi Byeok (1754–1785), a disciple of the Silhak scholar Yi Ik, encountered Seohak texts through Joseon envoys who brought them from Beijing.

He was a disciple of the Silhak scholar Yi Ik and maintained deep friendships with outstanding figures such as Yi Gahwan, Jeong Yakyong, Yi Seunghun, Gwon Cheolsin, and Gwon Ilsin. Through the envoys from Beijing, he came into contact with Seohak texts.

'As soon as I received many books from my friend, I rented a secluded house to dedicate myself to reading and contemplation.'

Seohak texts gradually spread throughout Joseon's intellectual society. By the late 1700s, there were few prominent officials or great Confucian scholars who had not read these texts. They regarded them similarly to the works of the Hundred Schools of Thought from China's Warring States period or Buddhist and Taoist texts. These books were often kept in their study rooms as valuable items to admire.

Based on his study of these Seohak texts, in 1777 (the first year of King Jeongjo's reign), Yi Byeok, along with close scholars such as Gwon Cheolsin and Jeong Yakjeon, held study sessions at Cheonjinam and Jueosa temples in Gwangju, Gyeonggi Province, where they began sharing their knowledge of Catholicism with fellow scholars.

Thus, Catholicism, under the name of Seohak (Western Learning), began to be studied and accepted independently by Joseon intellectuals about 30 years before Western missionaries arrived to evangelize.

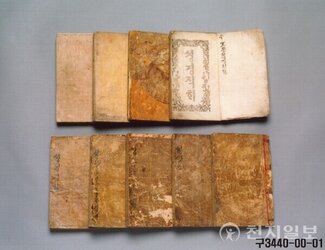

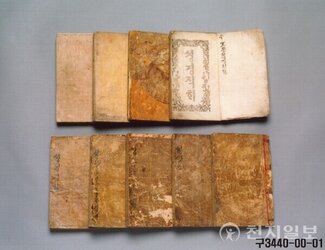

At that time, owning the original Chinese Seohak texts required direct purchase from Beijing, meaning that only a few individuals could have access to them. Another method was to borrow Chinese Seohak texts and copy them by hand to keep for personal study.

Kwon Ilsin, one of the early Catholic leaders and a member of the 'Myeongnyebang Community' (a faith group in Myeongdong, Seoul), had in his possession more than 50 hand-copied Catholic catechism books before the 1790s.

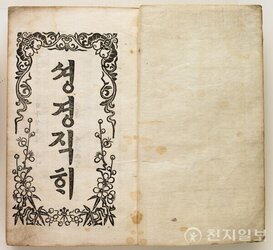

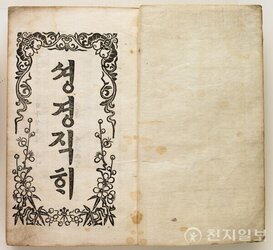

"Seonggyeong Jikhye" (National Museum of Korea)

Hangeul Seohak Texts

When French missionaries entered Joseon in the 1830s, they were greatly surprised. They discovered that the excellence of Hangul was significantly contributing to the spread of Catholicism.

"Almost all Catholics know how to read and write in their language using alphabet-like characters, which even young children learn very quickly." (Dallet, The Above-Mentioned Book, p. 13)

Half a century earlier, in the 1780s, indigenous Catholicism had been established and began spreading among the common people. However, the general populace could not freely read Seohak texts written in classical Chinese. Naturally, there arose a need to translate these Seohak texts into Hangul.

Once Seohak texts were translated into Hangul, Catholicism spread even more rapidly among the people. By around 1787, Hanguul-translated Seohak texts had become so widespread in regions like Chungcheong Province that they were memorized and passed down in nearly every household. These texts were also passed into the hands of women and children. The following historical record provides insight into the extent of this situation:

"By last spring (1787) and this summer (178 , in the Chungcheong area, Seohak texts were being memorized and transmitted in nearly every household. These texts were translated from classical Chinese into Hangul, copied and distributed, reaching even women and children." (Lee Gyu-gyeong, Cheoksagyo Panjeungseol, Oju Yeonmun Jangjeon Sango, Vol. 5, p. 705, from the counter-proposal of Jin-sa Hong Nak-an)

, in the Chungcheong area, Seohak texts were being memorized and transmitted in nearly every household. These texts were translated from classical Chinese into Hangul, copied and distributed, reaching even women and children." (Lee Gyu-gyeong, Cheoksagyo Panjeungseol, Oju Yeonmun Jangjeon Sango, Vol. 5, p. 705, from the counter-proposal of Jin-sa Hong Nak-an)

"Even extremely ignorant farmers and uneducated rural women would copy these books in the Korean script, treating them like sacred texts. Some would even stop working just to memorize and study them, to the point that they claimed they would not regret it even if they died." (Seungjeongwon Ilgi, Vol. 87, 12th Year of King Jeongjo (178 , August 2, p. 655)

, August 2, p. 655)

At that time, a representative Seohak text that was translated was Seonggyeong Jikhye, which was a translation of the book written by the Portuguese Jesuit missionary Diaz, first published in Beijing in 1636. This book translated the four Gospels, which are primarily read during Catholic Mass, and was translated by Choi Chang-hyun (1759–1801), who was one of the Catholic martyrs. He was beheaded during the Shinyu Persecution in 1801. About 30% of the four Gospels were translated and included in his version of Seonggyeong Jikhye.

Jeong Yak-jong, who was beheaded alongside Choi Chang-hyun, was the third brother of Jeong Yakyong. He wrote and disseminated the Catholic catechism Jugyo Yoji and also planned to compile the Seonggyo Jeonseo by referencing the Seohak texts that had been passed down until that time.

As Catholicism spread among the populace, the demand for Hangul Seohak texts grew even larger. The simplest way to distribute Hangul Seohak texts was through handwritten copies of the translated texts. Thus, it gradually became common for individuals to hand-copy Hangul Seohak texts for their own possession or to distribute them to those around them.

Kim Sajip from Cheongju noted, "He diligently learned to write and cultivated the knowledge to pass the state examination. As someone who wrote well, he copied many Catholic texts and generously gave the most essential books to fellow believers who could not afford them." He also mentioned, "Brother Augustin hid from people's eyes and worked as a boatman for a year, copying religious texts for his fellow believers."

As the number of Catholics increased, the demand for Hangul Seohak texts grew even greater. Consequently, some individuals began to seek out Hangul Seohak texts, even going so far as to purchase copied texts. The copied Seohak texts evolved into commodities, moving towards a stage where they were bought and sold for money.

Yi Johan studied writing in his spare time, copying many Catholic texts to sell and give to his fellow believers.”

“An Gun-sim spent most of his time copying sacred teaching texts to support the livelihood of his family and took pleasure in explaining the contents of these books not only to fellow believers but also to foreign visitors.”

These stories are found in Dalle’s History of Catholicism.

As a result, the Hangul Seohak texts that were obtained or purchased were regarded very highly by the church members. They were considered expensive due to the considerable effort involved in their creation. At a time when a sack of rice (石: 10 mal, 317 pounds) cost 5 nyang ($5 to $10), the price of one book was 1 nyang and 7 jeon ($1.70 to $2.00), roughly equivalent to the price of about 3 mal and a half of rice ($50 to $100).

Yanghwajin Jeoldusan Martyrs' Shrine

In the 1790s, there even emerged full-time scribes who made a living by copying Seohak texts. Jeon Gwang-su created Catholic books and traveled around selling them. As a result, “heretical books (referring to Seohak texts) became widely circulated, and scribes (those who specialized in copying books) began to earn significant profits,” leading to this situation.

Kim Sebak, a relative of Kim Beom-u, the first martyr of the Korean Catholic Church, converted to Catholicism shortly after the church was established. When he converted, his wife and children strongly rejected Catholicism, making it impossible for him to practice his faith.

In 1791, he left his family and traveled to find local believers, making a living by copying and selling Catholic texts. Taking it a step further, there were even those who hired professional copyists to create and sell Hangul catechisms.

During the persecution of Catholics, Catholic texts held by believers were also searched and confiscated as evidence. In the 1801 persecution, 120 types of Catholic texts were seized and burned, of which 83 were Hangul editions, indicating that the translation and possession of Catholic texts had been widely carried out.

The books that were copied could only be expensive due to the effort required for transcription, which meant they could not be widely disseminated. This led to the necessity for the establishment of printing houses and the printing of texts.

Around 1863, a printing house was established in Seoul, allowing for the cheap printing and distribution of many books. There were even two printing houses in Seoul. However, when persecution broke out again in 1866, the Catholic printing houses were sold, and the distribution of Hangul Seohak texts rapidly diminished.

Hangul translated Western Catholic texts originally written in Classical Chinese, making them accessible for the general public to read easily. The spirit of King Sejong's creation of Hangul was thus fully realized. Hangul played a significant role in embracing this new civilization.

Kim Beom-woo's Interpreter’s House of Learning (Illustration by Professor Kim Tae, Myeongdong Cathedral Collection)

The Introduction of Western Studies

Seohak (Western Learning) refers to the combination of Western science and technology, along with Catholic faith, introduced from Qing China starting in the early 1600s after the Japanese invasions of Korea (Imjin War). The devastating experiences of the Imjin War and the Manchu invasions (Byeongja War) exposed the limitations of the Neo-Confucian system, ideology, and civilization in Joseon.

Before long, Joseon became a weakened society, unable to recognize external threats or protect its own people, even when aware of them.

Across society, movements arose to search for a new path for Joseon. Among these was a growing interest among intellectuals in foreign, particularly Western, knowledge and civilization. Some exceptional scholars began to turn their attention to the light coming from the broader world beyond the rigid ideological boundaries of Neo-Confucianism, which had become like a prison.

Seohak was not something spread by any particular person; rather, it was Western civilization that Joseon intellectuals, driven by curiosity and a thirst for knowledge, sought out and adopted themselves, as they were deeply interested in the principles of the universe and the nature of things.

Initially, Seohak referred to knowledge from the West, but it gradually expanded to include the Catholic faith. As Catholicism spread among the general populace, Seohak became increasingly synonymous with Catholic texts and knowledge.

Joseon envoys frequently interacted with Qing scholars in Beijing, collecting Chinese books, paintings, and various fascinating artifacts of civilization to bring back to Korea.

During these visits, they also encountered Western Catholic missionaries in Beijing, through whom they gained access to Western scientific books and instruments written in classical Chinese, as well as Catholic catechisms, which they brought back to Joseon.

The intellectuals of Joseon, a country known for its scholarly pursuits, had learned classical Chinese from a young age, so they had little difficulty reading Seohak texts (Western Learning books) written in Chinese. Their interest in reforming the reality of Joseon and their curiosity about foreign knowledge drove them to eagerly study these texts.

Among these intellectuals...

Yi Byeok (1754–1785), a disciple of the Silhak scholar Yi Ik, encountered Seohak texts through Joseon envoys who brought them from Beijing.

He was a disciple of the Silhak scholar Yi Ik and maintained deep friendships with outstanding figures such as Yi Gahwan, Jeong Yakyong, Yi Seunghun, Gwon Cheolsin, and Gwon Ilsin. Through the envoys from Beijing, he came into contact with Seohak texts.

'As soon as I received many books from my friend, I rented a secluded house to dedicate myself to reading and contemplation.'

Seohak texts gradually spread throughout Joseon's intellectual society. By the late 1700s, there were few prominent officials or great Confucian scholars who had not read these texts. They regarded them similarly to the works of the Hundred Schools of Thought from China's Warring States period or Buddhist and Taoist texts. These books were often kept in their study rooms as valuable items to admire.

Based on his study of these Seohak texts, in 1777 (the first year of King Jeongjo's reign), Yi Byeok, along with close scholars such as Gwon Cheolsin and Jeong Yakjeon, held study sessions at Cheonjinam and Jueosa temples in Gwangju, Gyeonggi Province, where they began sharing their knowledge of Catholicism with fellow scholars.

Thus, Catholicism, under the name of Seohak (Western Learning), began to be studied and accepted independently by Joseon intellectuals about 30 years before Western missionaries arrived to evangelize.

At that time, owning the original Chinese Seohak texts required direct purchase from Beijing, meaning that only a few individuals could have access to them. Another method was to borrow Chinese Seohak texts and copy them by hand to keep for personal study.

Kwon Ilsin, one of the early Catholic leaders and a member of the 'Myeongnyebang Community' (a faith group in Myeongdong, Seoul), had in his possession more than 50 hand-copied Catholic catechism books before the 1790s.

"Seonggyeong Jikhye" (National Museum of Korea)

Hangeul Seohak Texts

When French missionaries entered Joseon in the 1830s, they were greatly surprised. They discovered that the excellence of Hangul was significantly contributing to the spread of Catholicism.

"Almost all Catholics know how to read and write in their language using alphabet-like characters, which even young children learn very quickly." (Dallet, The Above-Mentioned Book, p. 13)

Half a century earlier, in the 1780s, indigenous Catholicism had been established and began spreading among the common people. However, the general populace could not freely read Seohak texts written in classical Chinese. Naturally, there arose a need to translate these Seohak texts into Hangul.

Once Seohak texts were translated into Hangul, Catholicism spread even more rapidly among the people. By around 1787, Hanguul-translated Seohak texts had become so widespread in regions like Chungcheong Province that they were memorized and passed down in nearly every household. These texts were also passed into the hands of women and children. The following historical record provides insight into the extent of this situation:

"By last spring (1787) and this summer (178

"Even extremely ignorant farmers and uneducated rural women would copy these books in the Korean script, treating them like sacred texts. Some would even stop working just to memorize and study them, to the point that they claimed they would not regret it even if they died." (Seungjeongwon Ilgi, Vol. 87, 12th Year of King Jeongjo (178

At that time, a representative Seohak text that was translated was Seonggyeong Jikhye, which was a translation of the book written by the Portuguese Jesuit missionary Diaz, first published in Beijing in 1636. This book translated the four Gospels, which are primarily read during Catholic Mass, and was translated by Choi Chang-hyun (1759–1801), who was one of the Catholic martyrs. He was beheaded during the Shinyu Persecution in 1801. About 30% of the four Gospels were translated and included in his version of Seonggyeong Jikhye.

Jeong Yak-jong, who was beheaded alongside Choi Chang-hyun, was the third brother of Jeong Yakyong. He wrote and disseminated the Catholic catechism Jugyo Yoji and also planned to compile the Seonggyo Jeonseo by referencing the Seohak texts that had been passed down until that time.

As Catholicism spread among the populace, the demand for Hangul Seohak texts grew even larger. The simplest way to distribute Hangul Seohak texts was through handwritten copies of the translated texts. Thus, it gradually became common for individuals to hand-copy Hangul Seohak texts for their own possession or to distribute them to those around them.

Kim Sajip from Cheongju noted, "He diligently learned to write and cultivated the knowledge to pass the state examination. As someone who wrote well, he copied many Catholic texts and generously gave the most essential books to fellow believers who could not afford them." He also mentioned, "Brother Augustin hid from people's eyes and worked as a boatman for a year, copying religious texts for his fellow believers."

As the number of Catholics increased, the demand for Hangul Seohak texts grew even greater. Consequently, some individuals began to seek out Hangul Seohak texts, even going so far as to purchase copied texts. The copied Seohak texts evolved into commodities, moving towards a stage where they were bought and sold for money.

Yi Johan studied writing in his spare time, copying many Catholic texts to sell and give to his fellow believers.”

“An Gun-sim spent most of his time copying sacred teaching texts to support the livelihood of his family and took pleasure in explaining the contents of these books not only to fellow believers but also to foreign visitors.”

These stories are found in Dalle’s History of Catholicism.

As a result, the Hangul Seohak texts that were obtained or purchased were regarded very highly by the church members. They were considered expensive due to the considerable effort involved in their creation. At a time when a sack of rice (石: 10 mal, 317 pounds) cost 5 nyang ($5 to $10), the price of one book was 1 nyang and 7 jeon ($1.70 to $2.00), roughly equivalent to the price of about 3 mal and a half of rice ($50 to $100).

Yanghwajin Jeoldusan Martyrs' Shrine

In the 1790s, there even emerged full-time scribes who made a living by copying Seohak texts. Jeon Gwang-su created Catholic books and traveled around selling them. As a result, “heretical books (referring to Seohak texts) became widely circulated, and scribes (those who specialized in copying books) began to earn significant profits,” leading to this situation.

Kim Sebak, a relative of Kim Beom-u, the first martyr of the Korean Catholic Church, converted to Catholicism shortly after the church was established. When he converted, his wife and children strongly rejected Catholicism, making it impossible for him to practice his faith.

In 1791, he left his family and traveled to find local believers, making a living by copying and selling Catholic texts. Taking it a step further, there were even those who hired professional copyists to create and sell Hangul catechisms.

During the persecution of Catholics, Catholic texts held by believers were also searched and confiscated as evidence. In the 1801 persecution, 120 types of Catholic texts were seized and burned, of which 83 were Hangul editions, indicating that the translation and possession of Catholic texts had been widely carried out.

The books that were copied could only be expensive due to the effort required for transcription, which meant they could not be widely disseminated. This led to the necessity for the establishment of printing houses and the printing of texts.

Around 1863, a printing house was established in Seoul, allowing for the cheap printing and distribution of many books. There were even two printing houses in Seoul. However, when persecution broke out again in 1866, the Catholic printing houses were sold, and the distribution of Hangul Seohak texts rapidly diminished.

Hangul translated Western Catholic texts originally written in Classical Chinese, making them accessible for the general public to read easily. The spirit of King Sejong's creation of Hangul was thus fully realized. Hangul played a significant role in embracing this new civilization.