Chocolate Makers Try a New Recipe: Less Chocolate

Bloomberg (archive.ph)

By Ilena Peng

2024-02-29 11:00:16GMT

Photographer: Scott Semler for Bloomberg Businessweek; Prop stylist: Andrea Bonin

When Mars Inc. made a quiet tweak to its popular Galaxy chocolate bar last year, shaving 10 grams off the standard product size and repackaging the leaner treat without lowering the price, UK shoppers were surprised—but cocoa traders weren’t.

The 113-year-old company, best known for its packaged sweets including Twix and M&M’s, appeared to be taking a well-used page from the confectioners’ playbook: When the cost of cocoa rises, they find ways to sell households smaller doses of chocolate—or, for some candy makers, new goodies with no chocolate at all.

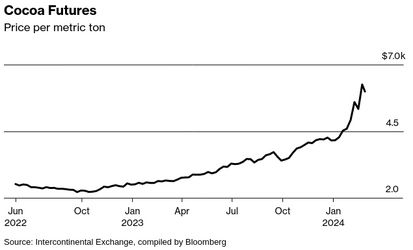

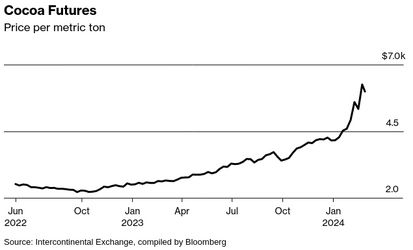

Cocoa prices have climbed to record highs, and market participants don’t expect any near-term relief. Prices have skyrocketed as the world’s biggest producers in West Africa grapple with drought and disease as well as structural problems that could linger for years to come. Futures traded in New York averaged well below $3,500 a metric ton every year from the 1980s until 2023. On Feb. 22 cocoa futures surpassed $6,000 a ton for the first time, and the market worries they could still have further to run.

“We have been actively trying to find ways to absorb the rising costs of raw materials and operations,” a Mars Wrigley UK spokesperson said in an email. “Reducing the size of our products is not a decision we have taken lightly.”

So far, companies have been passing on higher costs to consumers. But no one needs chocolate to live, and every price hike risks sales. Consumers are most likely to cut spending on chocolate and candy if inflation continues, behind only alcohol and makeup, according to a survey from September by consumer intelligence company NIQ.

“At the end of the day, at the cash register, it’s cost that is driving purchasing decisions as much as anything,” Brian McKeon, the National Confectioners Association’s senior vice president for public policy, said at the Amsterdam Cocoa Week conference in early February.

A raw cocoa bean.Photographer: Scott Semler for Bloomberg Businessweek; Prop stylist: Andrea Bonin

Facing limited room for additional price hikes, companies are shrinking packages, using automation to trim production costs and promoting products with less cocoa or other starring flavors. Nestlé SA recently introduced in the UK a hazelnut flavor in its bubbly Aero line of chocolate bars, which— at 36 grams each—are about one-third the weight of competing chocolate bars thanks to their namesake air pockets. In the US, where Kit Kat bars are made by Hershey Co., the latest addition to the permanent flavor lineup— Chocolate Frosted Donut

—relies on a partial dip of chocolate, not a full coating. This reduction pushes chocolate and cocoa butter farther down the ingredient list than in the classic Kit Kat.

Marketing focused on filled or lower-chocolate products “is definitely on the table,” says Billy Roberts, a senior economist for food and beverage at CoBank, a major provider of private credit to the US agriculture industry.

Today, more than 40% of molded and segmented chocolate bars sold in the US are filled with something else, be it caramel, nuts or fruit, says Carl Quash III, head of snacks and nutrition at Euromonitor International. “This trend was going down for a while, but now with the high costs of cocoa and consumers looking for indulgences, we will see more of these innovations come to market,” he says.

This shift was on full display for the nearly 124 million people watching the Super Bowl telecast in February. Instead of selling consumers on rich, traditional solid-chocolate options in multimillion-dollar commercial slots, candy giants Mars and Hershey respectively pitched peanut-butter-filled M&M’s and Reese’s cups with added caramel.

It’s “a way for them to leverage their biggest brand with effective advertising, with flavor innovation that utilizes something other than chocolate,” Jim Salera, an analyst at Stephens Inc., says of Reese’s splashy advertisement for its Caramel Big Cup.

Hershey declined to comment.

Cocoa butter, produced when beans are ground, is a key ingredient in chocolate. An average milk chocolate bar contains about 20% cocoa butter. But some food manufacturers are finding ways to replace some of the cocoa butter in their products with cheaper substitutes such as palm oil. Swedish company AAK AB, a maker of cocoa butter alternatives, says

the high price of cocoa and cocoa butter has led more customers to consider its products, though the wider trend of smaller candy bars—called “shrinkflation” in the food industry—has somewhat muted the impact.

The switch from cocoa butter to noncocoa substitutes works better with nonpremium chocolate applications, such as thin coatings on granola bars and fillings in bakery items, rather than more traditional chocolate bars. Noncocoa substitutes have long been more common in hot countries, where cocoa butter’s low melting point can pose a problem.

“Tinkering now with the recipes and flavor profiles simply because the input cost for cocoa has gone up, in my opinion, would be a mistake,” Nestlé Chief Executive Officer Mark Schneider said on a Feb. 22 call with journalists. The company might need to adjust marketing or brand support, he said, but “it’s just one more commodity cost variation that we tactically have to deal with.” For example, the industry also has faced high sugar costs lately.

Chocolate makers typically use the futures market to hedge risk, buying cocoa futures eight to nine months out as protection. Because of higher prices, some manufacturers let that protection slip to as low as six months at the end of last year in hopes that prices would come down. But cocoa kept on rising, forcing them to reenter the market; they’re still protected for only about seven or seven and a half months, says commodities broker Marex Group. Analysts at Morgan Stanley recently downgraded Hershey stock to underweight and noted that “the runup in cocoa that started in mid-2023 is likely to catch up with the company in 2025.”

Cocoa beans drying under the sun at a Ghanaian plantation in 2021.Photographer: Xu Zheng/Getty Images

High prices are encouraging companies to continue diversifying beyond chocolate. “Everyone is trying to become more of a holistic candy player,” says Nik Modi, co-head of global consumer and retail research at RBC Capital Markets. “Everyone is starting to really think hard about how to be bigger in that space because they see what’s happening with chocolate, which is the category that’s really been under pressure.”

At the annual Consumer Analyst Group of New York conference in Boca Raton, Florida, in late February, Hershey unveiled its latest plan for the future. The company, which has been manufacturing its iconic Kisses for more than a century and still counts Reese’s as its biggest brand, plans to boost its gummy candy capacity 50% in 2024. This push will help Hershey “reach our consumers in new and different ways,” CEO Michele Buck said as she invited former NBA star and new gummy partner Shaquille O’Neal to the stage.

“When these things come out, we want you to buy them, and we want you to invest in them, and we want you to have fun,” O’Neal said of the gummies, which he said he helped develop alongside Hershey. When visiting the research and development team lab of the company best known for its chocolate, “I was there eating gummies all day,” he said. —With Dasha Afanasieva, Deena Shanker and Mumbi Gitau

Bloomberg (archive.ph)

By Ilena Peng

2024-02-29 11:00:16GMT

Photographer: Scott Semler for Bloomberg Businessweek; Prop stylist: Andrea Bonin

When Mars Inc. made a quiet tweak to its popular Galaxy chocolate bar last year, shaving 10 grams off the standard product size and repackaging the leaner treat without lowering the price, UK shoppers were surprised—but cocoa traders weren’t.

The 113-year-old company, best known for its packaged sweets including Twix and M&M’s, appeared to be taking a well-used page from the confectioners’ playbook: When the cost of cocoa rises, they find ways to sell households smaller doses of chocolate—or, for some candy makers, new goodies with no chocolate at all.

Cocoa prices have climbed to record highs, and market participants don’t expect any near-term relief. Prices have skyrocketed as the world’s biggest producers in West Africa grapple with drought and disease as well as structural problems that could linger for years to come. Futures traded in New York averaged well below $3,500 a metric ton every year from the 1980s until 2023. On Feb. 22 cocoa futures surpassed $6,000 a ton for the first time, and the market worries they could still have further to run.

“We have been actively trying to find ways to absorb the rising costs of raw materials and operations,” a Mars Wrigley UK spokesperson said in an email. “Reducing the size of our products is not a decision we have taken lightly.”

So far, companies have been passing on higher costs to consumers. But no one needs chocolate to live, and every price hike risks sales. Consumers are most likely to cut spending on chocolate and candy if inflation continues, behind only alcohol and makeup, according to a survey from September by consumer intelligence company NIQ.

“At the end of the day, at the cash register, it’s cost that is driving purchasing decisions as much as anything,” Brian McKeon, the National Confectioners Association’s senior vice president for public policy, said at the Amsterdam Cocoa Week conference in early February.

A raw cocoa bean.Photographer: Scott Semler for Bloomberg Businessweek; Prop stylist: Andrea Bonin

Facing limited room for additional price hikes, companies are shrinking packages, using automation to trim production costs and promoting products with less cocoa or other starring flavors. Nestlé SA recently introduced in the UK a hazelnut flavor in its bubbly Aero line of chocolate bars, which— at 36 grams each—are about one-third the weight of competing chocolate bars thanks to their namesake air pockets. In the US, where Kit Kat bars are made by Hershey Co., the latest addition to the permanent flavor lineup— Chocolate Frosted Donut

—relies on a partial dip of chocolate, not a full coating. This reduction pushes chocolate and cocoa butter farther down the ingredient list than in the classic Kit Kat.

Marketing focused on filled or lower-chocolate products “is definitely on the table,” says Billy Roberts, a senior economist for food and beverage at CoBank, a major provider of private credit to the US agriculture industry.

Today, more than 40% of molded and segmented chocolate bars sold in the US are filled with something else, be it caramel, nuts or fruit, says Carl Quash III, head of snacks and nutrition at Euromonitor International. “This trend was going down for a while, but now with the high costs of cocoa and consumers looking for indulgences, we will see more of these innovations come to market,” he says.

This shift was on full display for the nearly 124 million people watching the Super Bowl telecast in February. Instead of selling consumers on rich, traditional solid-chocolate options in multimillion-dollar commercial slots, candy giants Mars and Hershey respectively pitched peanut-butter-filled M&M’s and Reese’s cups with added caramel.

It’s “a way for them to leverage their biggest brand with effective advertising, with flavor innovation that utilizes something other than chocolate,” Jim Salera, an analyst at Stephens Inc., says of Reese’s splashy advertisement for its Caramel Big Cup.

Hershey declined to comment.

Cocoa butter, produced when beans are ground, is a key ingredient in chocolate. An average milk chocolate bar contains about 20% cocoa butter. But some food manufacturers are finding ways to replace some of the cocoa butter in their products with cheaper substitutes such as palm oil. Swedish company AAK AB, a maker of cocoa butter alternatives, says

the high price of cocoa and cocoa butter has led more customers to consider its products, though the wider trend of smaller candy bars—called “shrinkflation” in the food industry—has somewhat muted the impact.

The switch from cocoa butter to noncocoa substitutes works better with nonpremium chocolate applications, such as thin coatings on granola bars and fillings in bakery items, rather than more traditional chocolate bars. Noncocoa substitutes have long been more common in hot countries, where cocoa butter’s low melting point can pose a problem.

“Tinkering now with the recipes and flavor profiles simply because the input cost for cocoa has gone up, in my opinion, would be a mistake,” Nestlé Chief Executive Officer Mark Schneider said on a Feb. 22 call with journalists. The company might need to adjust marketing or brand support, he said, but “it’s just one more commodity cost variation that we tactically have to deal with.” For example, the industry also has faced high sugar costs lately.

Chocolate makers typically use the futures market to hedge risk, buying cocoa futures eight to nine months out as protection. Because of higher prices, some manufacturers let that protection slip to as low as six months at the end of last year in hopes that prices would come down. But cocoa kept on rising, forcing them to reenter the market; they’re still protected for only about seven or seven and a half months, says commodities broker Marex Group. Analysts at Morgan Stanley recently downgraded Hershey stock to underweight and noted that “the runup in cocoa that started in mid-2023 is likely to catch up with the company in 2025.”

Cocoa beans drying under the sun at a Ghanaian plantation in 2021.Photographer: Xu Zheng/Getty Images

High prices are encouraging companies to continue diversifying beyond chocolate. “Everyone is trying to become more of a holistic candy player,” says Nik Modi, co-head of global consumer and retail research at RBC Capital Markets. “Everyone is starting to really think hard about how to be bigger in that space because they see what’s happening with chocolate, which is the category that’s really been under pressure.”

At the annual Consumer Analyst Group of New York conference in Boca Raton, Florida, in late February, Hershey unveiled its latest plan for the future. The company, which has been manufacturing its iconic Kisses for more than a century and still counts Reese’s as its biggest brand, plans to boost its gummy candy capacity 50% in 2024. This push will help Hershey “reach our consumers in new and different ways,” CEO Michele Buck said as she invited former NBA star and new gummy partner Shaquille O’Neal to the stage.

“When these things come out, we want you to buy them, and we want you to invest in them, and we want you to have fun,” O’Neal said of the gummies, which he said he helped develop alongside Hershey. When visiting the research and development team lab of the company best known for its chocolate, “I was there eating gummies all day,” he said. —With Dasha Afanasieva, Deena Shanker and Mumbi Gitau