L | A (Translated with ChatGPT)

On October 22, 1762, Russian Empress Catherine II the Great inscribed three short words, “So be it,” on the Senate’s report titled “On allocating the Mozdok locality for the settlement of Kabardians led by the ruler of Lesser Kabarda, Kurgoko Konchokin, the construction of a fortress there, and the transformation of Mozdok into a center for industry and trade.”

Mozdok was established on lands belonging to the Kabardian prince, whose transition to Russian allegiance and Christianity, as well as the need to protect him and his people, served as the basis for the annexation of this territory to Russia and the construction of the fortress.

This decision was further justified by the actions of his fellow tribesmen, who, in absentia, vowed to kill him, plunder his property, enslave his subjects, and seize his livestock.

It must be noted that they made every effort to achieve these goals.

Nevertheless, Konchokin’s actions were supported by thousands of Circassians from various tribes, ranging from princes to slaves. While the transition of a ruling prince along with all his subjects was handled at the highest level, ordinary nobles, free peasants, or slaves could simply approach a Cossack patrol or an army post and declare their intention to pledge allegiance to the White Tsar.

Teenagers of both sexes fled from families that had decided to sell them to Turkey. Others escaped blood feuds or grew tired of a life of banditry, seeking peaceful work under the protection of strong Russian authority. Interestingly, assimilation and conversion to Christianity were not mandatory.

The only requirements for highlanders who switched to the Russian side were loyalty and adherence to the laws. In return, they received protection, self-governance in peaceful villages, and numerous benefits, including exemptions from taxes and military service, as well as financial support. Their traditions and religion were left untouched.

Notably, the descendants of those Kabardians who were the first to pledge allegiance to Russia still live in Mozdok and, to some extent, in Prokhladny. They practice Orthodoxy and take great pride in their heritage.

That said, modern advocates of the "genocide of the Circassians" trace the beginning of the so-called "Russo-Circassian War" to the construction of the Mozdok fortress. However, if one interprets the relationship between the peoples of the Russian Empire and the Circassians purely as a war (which also included entirely peaceful elements of interaction), one could argue that it began much earlier.

Circassians participated in nearly all the plundering raids carried out by Crimean Tatars and the Nogai Horde against the Muscovite state and the lands of the Don Cossacks, and later against the southern borders of the Russian Empire. It is known that Circassians were part of the army of Mamai, the Tatar general defeated at the Battle of Kulikovo.

In light of this, the empire's southward expansion was primarily driven by the need to secure its borders. This was especially pressing given that Turkey, which had become Russia's main geopolitical rival in the 18th century, continuously incited Caucasian tribes to attack Russian lands.

Economic incentives played a role in this as well: the Turks eagerly purchased people captured during raids, turning the abduction of villagers for sale to slave traders into a crucial livelihood for Circassian warriors. In return, Turkish merchants supplied them with weapons, gunpowder, scarce salt, and other goods.

Turkish missionaries were active in Circassian villages, converting highlanders—who had previously practiced Christianity or adhered to pagan beliefs—to Islam and rallying them to wage war against the "infidels."

Meanwhile, up until the late 1810s, Russian policy in the Caucasus was clearly defensive.

For nearly 50 years after the construction of Mozdok, Cossacks and troops remained stationed on the right bank of the Kuban River, focusing solely on preventing raids by the "trans-Kuban predators." They refrained from encroaching on the lands of Circassian tribes and only crossed the Kuban and Laba Rivers reluctantly and in response to highland raids.

Throughout this period, Russia advocated for peace with the highlanders, sought trade relations, and endeavored to avoid conflicts. At one point, there was even a rule stipulating that any crossing of the Kuban River by troops required the personal approval of Emperor Paul I. Violators of this rule were harshly punished, regardless of the circumstances under which the breach occurred.

In 1797, over 300 Black Sea Cossacks, driven to near destitution by constant highlander raids, crossed the Kuban River without authorization, attacked a Circassian village, and seized up to 5,000 sheep.

When Emperor Paul I learned of the incident, he ordered the sheep returned to the Circassians, the regiment commander put on trial, and a message conveyed to the Cossacks that any repeat of such actions would result in the raiders being handed over to the Circassians.

Almost all documentation from that period reflects the overarching goal of avoiding provocation and primarily using peaceful means to influence the highlanders. Raids were euphemistically referred to as "pranks," and military commanders were instructed to prevent them, expel Circassians who had intruded onto Russian territory whenever possible, and only resort to destruction as a last resort.

However, such pacification methods often produced the opposite effect—raids increased, and the enemy, interpreting the tsarist government's restraint as a sign of weakness, grew increasingly bold.

Efforts to bribe the highland elites were also largely ineffective. Many princes sought to receive bribes from both the Russians and the Turks.

In addition to the increased activity of the "trans-Kuban predators," Russia was compelled to adopt an offensive strategy in the Caucasus due to the incorporation of Georgia into the empire and two wars with Turkey in the first half of the 19th century.

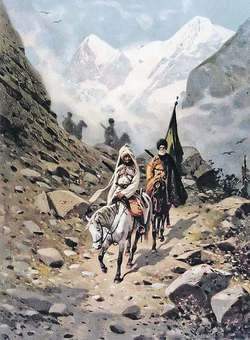

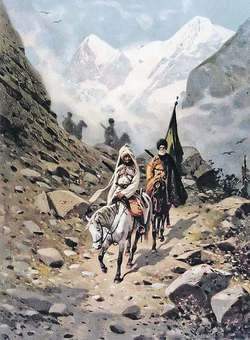

To disrupt the slave trade and weaken Turkish influence over the Circassian tribes, Russia established a chain of coastal fortifications and intensified naval patrols in the Black Sea. Troops crossed the Kuban River, initiating the construction of forts and fortified settlements on Circassian lands. A systematic campaign began against rebellious villages and irreconcilable highlanders.

Once the decision was made to occupy the entire Caucasus, the war's outcome was predetermined and apparent. Nevertheless, St. Petersburg consistently sought to minimize losses on both sides.

However, in 1861, Circassian leaders—having lost nearly everything, unable to oppose the massive Russian army, and standing on the brink of their people’s greatest tragedy—rejected another peace offer from Alexander II.

Encouraged by the Turks and now the British, they demanded nothing short of Russia's withdrawal beyond the Kuban River, the demolition of fortresses, and the surrender of dozens of compatriots who had accepted Russian allegiance.

It is important to note that for Circassian society, the Caucasian War bore distinct traits of a civil conflict.

As the renowned Caucasus historian Vasily Potto observed, he even drew parallels between events in the Trans-Kuban region and the French Revolution. Among the Circassians, there were supporters of both Turkish and Russian alignments. The irreconcilable factions despised the latter almost more than they hated the Cossacks and Russian soldiers.

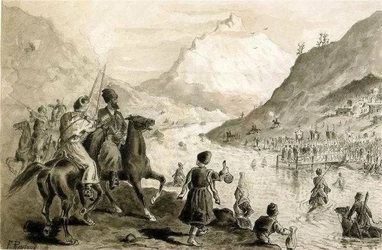

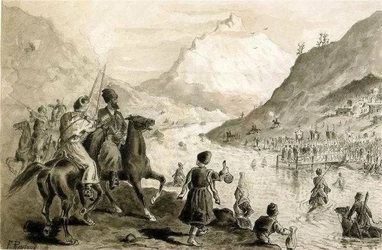

Finally, on May 21, 1864, Russian forces converged at Krasnaya Polyana, targeting the last pockets of resistance in the Western Caucasus. This day was declared the official end of the Caucasian War. To commemorate the event, the Caucasian Governor-General, Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich, held a military parade and a solemn thanksgiving service.

Deportation or Immigration?

The long and bloody war, which had brought untold suffering to all its participants, came to an end. A lasting peace was established on the war-torn lands of the Caucasus. Yet, surprisingly, not everyone welcomed this peace.

For example, the abolition of slavery and the trade in prisoners of war, civilian hostages, and even impoverished members of their own communities deprived rebellious highland clans of a significant source of income. Raiding, looting of settlements, and ambushes on peaceful villages and roads became impossible.

The leaders of the Circassian communities, like those of many other peoples caught between two powerful empires, had long skillfully maneuvered between the Turks, Russians, British, and their own tribesmen. They secured various benefits in exchange for apparent loyalty or actions against another side.

These benefits were often substantial and even vital, such as military support, financial and economic aid, or increased influence among other Circassian tribes.

However, with the unequivocal transition of Circassian territories under Russian jurisdiction, the possibility of such bargaining disappeared.

Russian authorities now demanded absolute loyalty, which was unacceptable for some members of the local elite. Additionally, by this time, serfdom had been abolished in the Russian Empire. This meant that local feudal lords lost their slaves and serfs, who, upon becoming Russian subjects, were granted freedom.

The Russian authorities were well aware that the highlanders, who had laid down their arms under the threat of annihilation, were far from truly subdued. Their compliance was temporary, likely only lasting until Russia faced a strong adversary in another war, at which point they would undoubtedly attempt to strike from behind.

The government understood the immense difficulty of monitoring loyalty and enforcing laws among militant communities secluded in mountain fortresses—auls in remote and inaccessible areas.

To mitigate this, the victors demanded that the most unyielding communities relocate to the plains of the Kuban region, fertile lands under the watchful eyes of Cossack settlements.

However, this demand was categorically rejected by several tribes, including the Ubykh. They found the idea of emigrating to Turkey, actively promoted by Turkish emissaries and agitators among the highlanders, far more appealing.

The Ottoman Empire’s interest in this matter was hardly altruistic. The Turkish military needed loyal and battle-ready recruits, and Istanbul planned to resettle these restless communities in volatile frontier regions of its empire, such as the Balkans and Arab territories.

These areas frequently rose against Ottoman oppression, and the Circassians, as outsiders, were expected to be hostile to the indigenous populations—Arabs, Serbs, Bulgarians, and Greeks.

Moreover, Circassian women had long been highly prized by Turkish hedonists, with their presence in the harems of sultans and pashas stretching back centuries. The anticipated migration promised an unprecedented "dumping" of this human commodity onto the market.

The Circassians themselves were oblivious to these ulterior motives. They were promised a land of milk and honey. The aristocracy hoped to retain their privileges and secure financial aid from the Sultan, while common folk dreamed of a prosperous and carefree life in a Turkish "paradise."

An Abkhaz acquaintance once recounted hearing from his grandfather how Turkish propagandists would tell trusting peasants that pumpkins the size of carriages grew in Turkey. They claimed that growing just a few of these pumpkins - eating one and selling the rest - would suffice to live comfortably for a year. Such were the deceptive tactics employed to promote the idea of muhajirism (emigration).

The term muhajir can be translated from Arabic as "fugitive" or "exile." Initially, muhajirs referred to the companions of Muhammad who migrated with the Prophet from Mecca to Medina. These individuals were essentially refugees, and the Prophet urged the people of Medina to provide them with shelter and protection.

Over time, the term muhajirism came to signify the mass migration of Muslims from non-Muslim states to Islamic countries, to avoid living as a religious minority under non-Islamic rule.

However, in the context of the Caucasian muhajirism, it is safe to say that religion played a secondary role in this movement.

By that time, the recently converted Circassians had embraced only certain aspects of Islam, particularly the ideas of waging war against "infidels" and the permissibility of appropriating the property of giaours (non-Muslims). In their daily lives, they were governed not by Sharia but by adat—customary laws rooted in pagan traditions.

Notably, in Shinkuba's The Last of the Departed, it is described how the "devout" Ubykh worshiped the goddess Bytkha and even took her idol with them to Turkey. This highlights that, in many Circassian tribes of the Western Caucasus, dual belief systems flourished, where Islam was adopted only superficially.

Interestingly, there were far fewer muhajirs in Chechnya and Dagestan, regions where adherence to Islam was significantly stronger. There were even fewer among the Turkic-speaking Karachays, Balkars, and Kumyks, who shared ethnic and linguistic ties with the Turks.

This phenomenon can be easily explained: the presence and activity of agitators promoting muhajirism were more pronounced in areas with higher numbers of muhajirs. Additionally, in Chechnya and Dagestan, where the wars had ended earlier, the population had already experienced life under Russian rule and realized it was not as fearsome as they had been led to believe.

How did the Russian authorities view the migration?

One could say that at first, the Russian authorities had a somewhat favorable view of muhajirism, believing that it would help rid the empire of the most troublesome and aggressive elements of society. However, when it became clear that the migration had turned into a truly massive movement, and unexpectedly included even peaceful, pro-Russian communities, the authorities grew alarmed.

Among the muhajirs were even pro-Russian Ossetians, who had not fought against the Russians. In fact, some of the muhajirs were senior officers from the Russian service. They were not attracted by tales of pumpkins the size of carriages.

An interesting example in this context is that of General-Major Musa Kundukhov (1818-1889), an Ossetian from a Muslim noble family.

He graduated from the Pavlovsk Military School in St. Petersburg and went on to lead the Military Ossetian and Chechen districts. He participated on the Russian side in several military campaigns, including the Caucasian and Crimean wars, the suppression of the Kraków Uprising (1846), the Hungarian Revolution (1849), and the disturbances in the North Caucasus in the 1860s.

However, after retiring in 1864, Kundukhov, in exchange for a reward of 10,000 rubles in silver, organized the resettlement of more than 5,000 families of Chechens, Ingush, and several dozen Muslim Ossetians to the Ottoman Empire. What was even more remarkable was that the clever general managed to obtain compensation from the Russian government of 45,000 rubles in silver for the land and property left behind in the Caucasus.

After settling in the Sivas vilayet, Kundukhov eventually reached a high military rank in the Ottoman Army, becoming a pasha in the rank of mirliva. He even participated in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 on the Turkish side!

Fearing that these new territories of the Russian Empire might be left without inhabitants, the authorities tried to counter this migration with propaganda, but with little success. One notable example is the proclamation by A. I. Baryatinsky, refuting the absurd rumors that had spread.

However, the mountain people were more inclined to believe the promises of the Turkish Sultan, who offered the muhajirs the lands of Armenians who had already moved to Russia, along with tax exemptions and financial aid.

There were also opponents of the muhajir movement among the mountain military and Muslim elites. Figures such as Natukhai Kostank-efendi (Kushtanok), Abadzeh Karabatyr-bey (Haji Batyrbey), and other popular preachers tried to dissuade the highlanders from this hasty decision.

However, they were in the minority, as rumors spread among the mountain people about forced baptisms, conscription, and becoming Cossacks, which fueled fears and doubts.

As we can see, the notion of deportation was never considered - the authorities even tried to dissuade the mountain people from muhajirism.

Interestingly, Bagrat Shinkuba was accused of intentionally tarnishing the reputation of the Ubykh princes to please Soviet censors and "class theory" by portraying them in his novel as petty, selfish individuals only interested in their own fate, rather than that of their people.

However, these accusations are unjust - the lion's share of the responsibility for the exile of the Circassian people lies with their own elite, bought off by Turkish and English agents. The societies of the North Caucasus had a complex social and clan structure with tight internal connections, which played a huge role in the local population’s life. This often led to entire clans following influential figures who decided to emigrate.

Another category of highlanders — dependent peasants and slaves — left with their masters in accordance with their owners' decisions, sometimes even against their will. Often, the peasants and slaves agreed to emigrate "only to avoid being sold into worse hands," unaware that under Russian rule, they would become free.

The first tragedy of the immigrants began almost immediately. People left their villages, destroying their homes and crops (so that they wouldn't fall into the hands of the "infidels") and headed to the ports where Turkish ships were supposed to be waiting for them. Neither Russia nor Turkey were prepared for such a massive influx of refugees.

They gathered in large numbers on the shores of the Black Sea, staying there for months, suffering and dying from hunger, cold, and infectious diseases. Many abandoned Circassian orphans, who had lost their parents, were picked up and adopted by the Cossacks. Not all those who were "fortunate" enough to board the ships were lucky enough to see Turkish shores.

"The living and healthy had no time to think about the dying; their own prospects were no more comforting; Turkish skippers, out of greed, piled the Circassians on board like cargo, hiring them to row their boats to Asia Minor, and, like cargo, threw overboard any who showed the slightest sign of illness…Hardly half of those who set sail for Turkey arrived at their destination. Such a disaster, of such scale, rarely befell humanity." [I. Drozdov. The Last Struggle with the Mountaineers of the Western Caucasus // Caucasian Collection. 1877. Vol. 2, p. 548].

However, even on the shores of Asia Minor in Turkey, where the ships with immigrants arrived, they were greeted by quarantine camps, often lacking proper living and food conditions. As a result, the Sultan was forced to issue a special decree forbidding the highlanders from selling their children and wives, who attempted, by this means, to save their loved ones from starving to death in the camps.

Thus, the Turkish monarch sought to enforce quarantine measures - too many Turks, hearing about the opportunity to buy "live goods" cheaply, rushed to the camps on the coast.

Finally, seeing the full horror of the situation, in 1867, the Caucasian viceroy, Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich, visiting the Kuban region, "personally informed the highlanders that their relocation to Turkey should cease definitively." However, even after this, there were those who, unwilling to give up on the "Turkish dream," became muhajirs.

The Remnants

As a result of the tragedy known in history as "muhajirism," only a small part of the once numerous Circassian people remained in their homeland. However, their fate turned out to be quite fortunate.

The princes integrated into the ranks of the Russian aristocracy, and common people gained the opportunity for peaceful work under the protection of strong authority. No one encroached upon the religion, traditions, or self-government of the highlanders. Soon, their relations with the Kuban Cossacks became very friendly.

The new Russian subjects received a number of privileges, including exemption from certain taxes and military service.

A number of gymnasiums were established in southern Russia, such as the Stavropol and Yekaterinodar Gymnasiums, where boarding schools for the children of the mountaineers were opened. At the Stavropol Gymnasium, the quota for the Circassians was 65 people, and at the Yekaterinodar Gymnasium, it was 25.

By official order, places were reserved for Circassian children in schools of large Cossack settlements, such as Pavlovskaya and Umanskaya.

In 1859, Emperor Alexander II approved a special Charter for Mountain Schools. According to it, the goal of the schools was "to spread civility and education among the subdued peaceful highlanders and to provide means for officers and officials serving in the Caucasus to raise and educate their children."

A circular from the Ministry of Education in 1867 stated that "gradually educating the foreign peoples, bringing them closer to the Russian spirit and to Russia, constitutes a task of the greatest political importance."

After finishing these schools, young Circassian men had the right to enter higher military schools, from which they graduated as officers and went on to serve in the army. A certain number of Adyghes also entered the best civilian universities in the country.

For example, the Adyghe Shumaf Tatlok graduated from Moscow University in 1859, became a candidate of law, and was retained for work in Moscow. This same university was also attended by the well-known public figure of Kabarda, L. M. Kodzokov, and other Adyghe educators, such as Kazi Atazhukin, Adil-Giray Kesev, and Sultan Krym-Giray Inatov, studied at St. Petersburg University.

At the same time, several individuals began to create the Adyghe alphabet. Even before the end of the Caucasian War, the Circassians had their own writers, doctors, teachers, historians, philologists, and mathematicians. They enlightened the people, gave them their own Adyghe alphabet, treated them, and wrote their history. The ethnographer Leonid Yakovlevich Lyulye developed the "Circassian Lexicon with a Brief Grammar," which was published in 1846, where he presented his version of the Adyghe alphabet.

And it must be said, the Adyghes responded with true loyalty. Circassian volunteers participated in all subsequent wars of the empire, earning undying glory.

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, a large militia of Adyghes fought in the Russian army. In addition to other units and regiments, the Kabardino-Gorsk and Kabardino-Kumyksky cavalry irregular regiments were formed on the Terek, mainly consisting of Kabardins, and on the Kuban — the Kuban-Gorsk cavalry irregular regiments, the Labinsky Squadron, and so on.

During this period, the Kabardian nobleman, Colonel (who became a Major General in 1890) Altadukov Tepsaruko Khamurzanovich (also Altudokov Tepsoruko Khadzhimurzovich), commander of the 2nd Mountain-Mozdok Cavalry Regiment of the Tersk Cossack Army, was awarded the Order of St. George 4th Class on June 9, 1878, "for distinguished service in actions against the Turks during the capture of the enemy position at Deivo-Boynu on October 23, 1877."

Another Kabardian, Colonel (who became a Lieutenant General in 1892) Shipchev Temirkhan Aktolovich (1830-1904), who commanded a regiment of the Kuban Cossack Army, was awarded the Order of St. George 4th Class on March 24, 1880, "for outstanding military feats displayed on July 24, 1877, near the village of Khalfaly."

Altadukov and Shipchev, for their distinction in this war, were also awarded the Gold Weapon with the inscription "For Bravery" (since 1913, the Georgievskoye weapon).

The following fact testifies to the role the highlanders played in the Armed Forces of the Empire: it was customary for Muslim cavalrymen and Orthodox commanders to exchange Easter greetings, and vice versa.

The long-standing cooperation between Muslims and Orthodox Christians in the Imperial Army led to customs that did not infringe upon either side. For example, one of the duties of the adjutant of the Kabardian Cavalry Regiment during communal lunches and dinners in the officers' mess was to count how many Muslims and how many Christians were present.

If Muslims made up the majority at the table, everyone remained in their papakhas (traditional hats), but if Christians were the majority, the papakhas were removed (according to Kabardian custom, the officers of the regiment always wore papakhas at home and only removed them when going to bed).

This approach shows an understanding and respect for the traditions of different nationalities and cultures. Religious differences and the multiethnic nature of the military contingents did not cause any conflicts within the ranks of the Russian Imperial Army.

During the Great Patriotic War, 20 sons of the Adyghe people were honored with the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. This small yet remarkable people of Russia has produced many outstanding scientists, writers, composers, and athletes.

Since the 1920s, there have been mountain autonomous regions in the USSR. Newspapers, magazines, educational, literary, and journalistic works have been and continue to be published in Kabardian and Adyghe dialects. Television and radio broadcasts are conducted, and theaters are in operation. Numerous choreographic and vocal ensembles are active.

The language continues to be studied in scientific research and taught in educational institutions. There are no restrictions on its use.

"The Turks "accepted" us in a way I would not wish upon you"

The fate of the muhajirs unfolded quite differently. Some, like Musa Kundukhov, easily integrated into the Turkish elite, but they were the exception. The rest were treated by the Turks as cannon fodder and cheap labor. The most significant hardship, however, was the forced assimilation they endured.

Shinkuba describes this process in detail: the Ubykhs changed their names and surnames, women were no longer allowed to attend celebrations or gatherings, and they were forced to wear the chador.

The Turkish aristocracy quickly renounced their people, their customs, and their native language. The people were left to fend for themselves and faced many hardships. Over time, the younger generation forgot the language, the goddess Bytha was taken, and there were no more priests.

Shinkuba contrasts two paths: the Abkhaz, unwilling to shift their allegiance between rulers, chose the White Tsar and never wavered from that decision. The Ubykh leader, initially accepting a rank and stipend from the Tsar, eventually defected to the Turks, bringing along the clans under his command. By the end of the 19th century, neither the Abkhaz nor the Ubykhs had a written language.

However, the Abkhaz managed to acquire one and preserved their language. The few attempts by the enthusiast Tagir to teach Ubykh children in their native language were suppressed, and the handwritten alphabet was destroyed. Other advocates for the language also failed in their efforts.

The Tragic "Fortune"

However, the Ubykhs did not physically disappear. It was their language that vanished. Their descendants switched to Turkish, although many of them still retain memories of their Ubykh roots.

In Turkey, there are several villages on the coast of the Sea of Marmara where Turks — descendants of the Ubykhs — live. Some of them know their genealogy. However, despite this knowledge, their mentality is completely different now — Turkish.

Today, propagandists attempting to play the "Circassian card" against Russia accuse our country of the total destruction of the Ubykhs. But the reality is that this ethnic group, in fact, (compared to other Adyghe tribes) almost never fought against Russia, with the exception of a few attacks on the forts of the Coastal Line.

Apart from two or three small operations carried out by the Russians from the territory of Abkhazia and a few coastal fortresses, the Russian soldier set foot on the land of this tribe only in 1864, in the final days of the war.

On March 4th, General Geyman sends a letter to the Ubykh elders with an ultimatum of resettlement either to Turkey or to Kuban. On March 9th, the Ubykhs respond, declaring their surrender and requesting three months to resettle to Turkey. The unit continued its movement eastward.

On March 18th, near the mouth of a small river, Ghodlik, a relatively large battle occurs with a group of rebellious Ubykhs and other small tribes. Russian forces quickly defeat the mountain dwellers, and Ubykhs no longer take part in military actions nor are subjected to any reprisals.

Due to this, the Ubykhs — unlike other Circassian tribes — were able to preserve their organization, order, and governance up to the very end and even after surrender.

While other Circassian communities, misled by their nobility and Turkish agitators, fled in disarray to the Black Sea ports and harbors for departure to Turkey (which largely caused the tragedy of 1864 and the massive losses of Adyghe during resettlement), the Ubykhs maintained order, organized ship rentals, and obeyed their leaders' will, departing peacefully within two weeks without any losses — neither of infants nor of the elderly.

The most significant aspect is that the Ubykhs were the only Adyghe ethnic group to emigrate to Turkey almost in its entirety. A total of 74,500 Ubykhs left, while only a few dozen of this tribe remained on the homeland.

Thus, the tribe, which suffered least during the Caucasian War and managed to emigrate without losses, disappeared completely, becoming assimilated, losing its language and culture, while the ethnic groups who remained "under the heel of the conquerors" were able to preserve their language, traditions, and develop their culture. Bagrat Shinkuba conveys all of this with utmost accuracy.

An even more succinct Abkhaz proverb sums it up: "He who loses his homeland loses all."

The irreconcilable Circassians became a losing card in the underhanded game between Turkey and Great Britain, which ultimately led to their greatest tragedy — the loss of their identity, national self-awareness, and culture.

However, today the "Circassian card" is once again being used against Russia.

Now, alongside Turkey, the USA, the EU, Georgia, and even Israel are involved. To this end, dishonest speculations about historical events that occurred 160 years ago are being spread. The enemies of our country are doing everything they can to drive a wedge between the Adyghe peoples and their neighbors, creating a new point of tension in the Caucasus.

On October 22, 1762, Russian Empress Catherine II the Great inscribed three short words, “So be it,” on the Senate’s report titled “On allocating the Mozdok locality for the settlement of Kabardians led by the ruler of Lesser Kabarda, Kurgoko Konchokin, the construction of a fortress there, and the transformation of Mozdok into a center for industry and trade.”

Mozdok was established on lands belonging to the Kabardian prince, whose transition to Russian allegiance and Christianity, as well as the need to protect him and his people, served as the basis for the annexation of this territory to Russia and the construction of the fortress.

This decision was further justified by the actions of his fellow tribesmen, who, in absentia, vowed to kill him, plunder his property, enslave his subjects, and seize his livestock.

It must be noted that they made every effort to achieve these goals.

Nevertheless, Konchokin’s actions were supported by thousands of Circassians from various tribes, ranging from princes to slaves. While the transition of a ruling prince along with all his subjects was handled at the highest level, ordinary nobles, free peasants, or slaves could simply approach a Cossack patrol or an army post and declare their intention to pledge allegiance to the White Tsar.

Teenagers of both sexes fled from families that had decided to sell them to Turkey. Others escaped blood feuds or grew tired of a life of banditry, seeking peaceful work under the protection of strong Russian authority. Interestingly, assimilation and conversion to Christianity were not mandatory.

The only requirements for highlanders who switched to the Russian side were loyalty and adherence to the laws. In return, they received protection, self-governance in peaceful villages, and numerous benefits, including exemptions from taxes and military service, as well as financial support. Their traditions and religion were left untouched.

Notably, the descendants of those Kabardians who were the first to pledge allegiance to Russia still live in Mozdok and, to some extent, in Prokhladny. They practice Orthodoxy and take great pride in their heritage.

That said, modern advocates of the "genocide of the Circassians" trace the beginning of the so-called "Russo-Circassian War" to the construction of the Mozdok fortress. However, if one interprets the relationship between the peoples of the Russian Empire and the Circassians purely as a war (which also included entirely peaceful elements of interaction), one could argue that it began much earlier.

Circassians participated in nearly all the plundering raids carried out by Crimean Tatars and the Nogai Horde against the Muscovite state and the lands of the Don Cossacks, and later against the southern borders of the Russian Empire. It is known that Circassians were part of the army of Mamai, the Tatar general defeated at the Battle of Kulikovo.

In light of this, the empire's southward expansion was primarily driven by the need to secure its borders. This was especially pressing given that Turkey, which had become Russia's main geopolitical rival in the 18th century, continuously incited Caucasian tribes to attack Russian lands.

Economic incentives played a role in this as well: the Turks eagerly purchased people captured during raids, turning the abduction of villagers for sale to slave traders into a crucial livelihood for Circassian warriors. In return, Turkish merchants supplied them with weapons, gunpowder, scarce salt, and other goods.

Turkish missionaries were active in Circassian villages, converting highlanders—who had previously practiced Christianity or adhered to pagan beliefs—to Islam and rallying them to wage war against the "infidels."

Meanwhile, up until the late 1810s, Russian policy in the Caucasus was clearly defensive.

For nearly 50 years after the construction of Mozdok, Cossacks and troops remained stationed on the right bank of the Kuban River, focusing solely on preventing raids by the "trans-Kuban predators." They refrained from encroaching on the lands of Circassian tribes and only crossed the Kuban and Laba Rivers reluctantly and in response to highland raids.

Throughout this period, Russia advocated for peace with the highlanders, sought trade relations, and endeavored to avoid conflicts. At one point, there was even a rule stipulating that any crossing of the Kuban River by troops required the personal approval of Emperor Paul I. Violators of this rule were harshly punished, regardless of the circumstances under which the breach occurred.

In 1797, over 300 Black Sea Cossacks, driven to near destitution by constant highlander raids, crossed the Kuban River without authorization, attacked a Circassian village, and seized up to 5,000 sheep.

When Emperor Paul I learned of the incident, he ordered the sheep returned to the Circassians, the regiment commander put on trial, and a message conveyed to the Cossacks that any repeat of such actions would result in the raiders being handed over to the Circassians.

Almost all documentation from that period reflects the overarching goal of avoiding provocation and primarily using peaceful means to influence the highlanders. Raids were euphemistically referred to as "pranks," and military commanders were instructed to prevent them, expel Circassians who had intruded onto Russian territory whenever possible, and only resort to destruction as a last resort.

However, such pacification methods often produced the opposite effect—raids increased, and the enemy, interpreting the tsarist government's restraint as a sign of weakness, grew increasingly bold.

Efforts to bribe the highland elites were also largely ineffective. Many princes sought to receive bribes from both the Russians and the Turks.

In addition to the increased activity of the "trans-Kuban predators," Russia was compelled to adopt an offensive strategy in the Caucasus due to the incorporation of Georgia into the empire and two wars with Turkey in the first half of the 19th century.

To disrupt the slave trade and weaken Turkish influence over the Circassian tribes, Russia established a chain of coastal fortifications and intensified naval patrols in the Black Sea. Troops crossed the Kuban River, initiating the construction of forts and fortified settlements on Circassian lands. A systematic campaign began against rebellious villages and irreconcilable highlanders.

Once the decision was made to occupy the entire Caucasus, the war's outcome was predetermined and apparent. Nevertheless, St. Petersburg consistently sought to minimize losses on both sides.

However, in 1861, Circassian leaders—having lost nearly everything, unable to oppose the massive Russian army, and standing on the brink of their people’s greatest tragedy—rejected another peace offer from Alexander II.

Encouraged by the Turks and now the British, they demanded nothing short of Russia's withdrawal beyond the Kuban River, the demolition of fortresses, and the surrender of dozens of compatriots who had accepted Russian allegiance.

It is important to note that for Circassian society, the Caucasian War bore distinct traits of a civil conflict.

As the renowned Caucasus historian Vasily Potto observed, he even drew parallels between events in the Trans-Kuban region and the French Revolution. Among the Circassians, there were supporters of both Turkish and Russian alignments. The irreconcilable factions despised the latter almost more than they hated the Cossacks and Russian soldiers.

Finally, on May 21, 1864, Russian forces converged at Krasnaya Polyana, targeting the last pockets of resistance in the Western Caucasus. This day was declared the official end of the Caucasian War. To commemorate the event, the Caucasian Governor-General, Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich, held a military parade and a solemn thanksgiving service.

Deportation or Immigration?

The long and bloody war, which had brought untold suffering to all its participants, came to an end. A lasting peace was established on the war-torn lands of the Caucasus. Yet, surprisingly, not everyone welcomed this peace.

For example, the abolition of slavery and the trade in prisoners of war, civilian hostages, and even impoverished members of their own communities deprived rebellious highland clans of a significant source of income. Raiding, looting of settlements, and ambushes on peaceful villages and roads became impossible.

The leaders of the Circassian communities, like those of many other peoples caught between two powerful empires, had long skillfully maneuvered between the Turks, Russians, British, and their own tribesmen. They secured various benefits in exchange for apparent loyalty or actions against another side.

These benefits were often substantial and even vital, such as military support, financial and economic aid, or increased influence among other Circassian tribes.

However, with the unequivocal transition of Circassian territories under Russian jurisdiction, the possibility of such bargaining disappeared.

Russian authorities now demanded absolute loyalty, which was unacceptable for some members of the local elite. Additionally, by this time, serfdom had been abolished in the Russian Empire. This meant that local feudal lords lost their slaves and serfs, who, upon becoming Russian subjects, were granted freedom.

The Russian authorities were well aware that the highlanders, who had laid down their arms under the threat of annihilation, were far from truly subdued. Their compliance was temporary, likely only lasting until Russia faced a strong adversary in another war, at which point they would undoubtedly attempt to strike from behind.

The government understood the immense difficulty of monitoring loyalty and enforcing laws among militant communities secluded in mountain fortresses—auls in remote and inaccessible areas.

To mitigate this, the victors demanded that the most unyielding communities relocate to the plains of the Kuban region, fertile lands under the watchful eyes of Cossack settlements.

However, this demand was categorically rejected by several tribes, including the Ubykh. They found the idea of emigrating to Turkey, actively promoted by Turkish emissaries and agitators among the highlanders, far more appealing.

The Ottoman Empire’s interest in this matter was hardly altruistic. The Turkish military needed loyal and battle-ready recruits, and Istanbul planned to resettle these restless communities in volatile frontier regions of its empire, such as the Balkans and Arab territories.

These areas frequently rose against Ottoman oppression, and the Circassians, as outsiders, were expected to be hostile to the indigenous populations—Arabs, Serbs, Bulgarians, and Greeks.

Moreover, Circassian women had long been highly prized by Turkish hedonists, with their presence in the harems of sultans and pashas stretching back centuries. The anticipated migration promised an unprecedented "dumping" of this human commodity onto the market.

The Circassians themselves were oblivious to these ulterior motives. They were promised a land of milk and honey. The aristocracy hoped to retain their privileges and secure financial aid from the Sultan, while common folk dreamed of a prosperous and carefree life in a Turkish "paradise."

An Abkhaz acquaintance once recounted hearing from his grandfather how Turkish propagandists would tell trusting peasants that pumpkins the size of carriages grew in Turkey. They claimed that growing just a few of these pumpkins - eating one and selling the rest - would suffice to live comfortably for a year. Such were the deceptive tactics employed to promote the idea of muhajirism (emigration).

The term muhajir can be translated from Arabic as "fugitive" or "exile." Initially, muhajirs referred to the companions of Muhammad who migrated with the Prophet from Mecca to Medina. These individuals were essentially refugees, and the Prophet urged the people of Medina to provide them with shelter and protection.

Over time, the term muhajirism came to signify the mass migration of Muslims from non-Muslim states to Islamic countries, to avoid living as a religious minority under non-Islamic rule.

However, in the context of the Caucasian muhajirism, it is safe to say that religion played a secondary role in this movement.

By that time, the recently converted Circassians had embraced only certain aspects of Islam, particularly the ideas of waging war against "infidels" and the permissibility of appropriating the property of giaours (non-Muslims). In their daily lives, they were governed not by Sharia but by adat—customary laws rooted in pagan traditions.

Notably, in Shinkuba's The Last of the Departed, it is described how the "devout" Ubykh worshiped the goddess Bytkha and even took her idol with them to Turkey. This highlights that, in many Circassian tribes of the Western Caucasus, dual belief systems flourished, where Islam was adopted only superficially.

Interestingly, there were far fewer muhajirs in Chechnya and Dagestan, regions where adherence to Islam was significantly stronger. There were even fewer among the Turkic-speaking Karachays, Balkars, and Kumyks, who shared ethnic and linguistic ties with the Turks.

This phenomenon can be easily explained: the presence and activity of agitators promoting muhajirism were more pronounced in areas with higher numbers of muhajirs. Additionally, in Chechnya and Dagestan, where the wars had ended earlier, the population had already experienced life under Russian rule and realized it was not as fearsome as they had been led to believe.

How did the Russian authorities view the migration?

One could say that at first, the Russian authorities had a somewhat favorable view of muhajirism, believing that it would help rid the empire of the most troublesome and aggressive elements of society. However, when it became clear that the migration had turned into a truly massive movement, and unexpectedly included even peaceful, pro-Russian communities, the authorities grew alarmed.

Among the muhajirs were even pro-Russian Ossetians, who had not fought against the Russians. In fact, some of the muhajirs were senior officers from the Russian service. They were not attracted by tales of pumpkins the size of carriages.

An interesting example in this context is that of General-Major Musa Kundukhov (1818-1889), an Ossetian from a Muslim noble family.

He graduated from the Pavlovsk Military School in St. Petersburg and went on to lead the Military Ossetian and Chechen districts. He participated on the Russian side in several military campaigns, including the Caucasian and Crimean wars, the suppression of the Kraków Uprising (1846), the Hungarian Revolution (1849), and the disturbances in the North Caucasus in the 1860s.

However, after retiring in 1864, Kundukhov, in exchange for a reward of 10,000 rubles in silver, organized the resettlement of more than 5,000 families of Chechens, Ingush, and several dozen Muslim Ossetians to the Ottoman Empire. What was even more remarkable was that the clever general managed to obtain compensation from the Russian government of 45,000 rubles in silver for the land and property left behind in the Caucasus.

After settling in the Sivas vilayet, Kundukhov eventually reached a high military rank in the Ottoman Army, becoming a pasha in the rank of mirliva. He even participated in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 on the Turkish side!

Fearing that these new territories of the Russian Empire might be left without inhabitants, the authorities tried to counter this migration with propaganda, but with little success. One notable example is the proclamation by A. I. Baryatinsky, refuting the absurd rumors that had spread.

However, the mountain people were more inclined to believe the promises of the Turkish Sultan, who offered the muhajirs the lands of Armenians who had already moved to Russia, along with tax exemptions and financial aid.

There were also opponents of the muhajir movement among the mountain military and Muslim elites. Figures such as Natukhai Kostank-efendi (Kushtanok), Abadzeh Karabatyr-bey (Haji Batyrbey), and other popular preachers tried to dissuade the highlanders from this hasty decision.

However, they were in the minority, as rumors spread among the mountain people about forced baptisms, conscription, and becoming Cossacks, which fueled fears and doubts.

As we can see, the notion of deportation was never considered - the authorities even tried to dissuade the mountain people from muhajirism.

Interestingly, Bagrat Shinkuba was accused of intentionally tarnishing the reputation of the Ubykh princes to please Soviet censors and "class theory" by portraying them in his novel as petty, selfish individuals only interested in their own fate, rather than that of their people.

However, these accusations are unjust - the lion's share of the responsibility for the exile of the Circassian people lies with their own elite, bought off by Turkish and English agents. The societies of the North Caucasus had a complex social and clan structure with tight internal connections, which played a huge role in the local population’s life. This often led to entire clans following influential figures who decided to emigrate.

Another category of highlanders — dependent peasants and slaves — left with their masters in accordance with their owners' decisions, sometimes even against their will. Often, the peasants and slaves agreed to emigrate "only to avoid being sold into worse hands," unaware that under Russian rule, they would become free.

The first tragedy of the immigrants began almost immediately. People left their villages, destroying their homes and crops (so that they wouldn't fall into the hands of the "infidels") and headed to the ports where Turkish ships were supposed to be waiting for them. Neither Russia nor Turkey were prepared for such a massive influx of refugees.

They gathered in large numbers on the shores of the Black Sea, staying there for months, suffering and dying from hunger, cold, and infectious diseases. Many abandoned Circassian orphans, who had lost their parents, were picked up and adopted by the Cossacks. Not all those who were "fortunate" enough to board the ships were lucky enough to see Turkish shores.

"The living and healthy had no time to think about the dying; their own prospects were no more comforting; Turkish skippers, out of greed, piled the Circassians on board like cargo, hiring them to row their boats to Asia Minor, and, like cargo, threw overboard any who showed the slightest sign of illness…Hardly half of those who set sail for Turkey arrived at their destination. Such a disaster, of such scale, rarely befell humanity." [I. Drozdov. The Last Struggle with the Mountaineers of the Western Caucasus // Caucasian Collection. 1877. Vol. 2, p. 548].

However, even on the shores of Asia Minor in Turkey, where the ships with immigrants arrived, they were greeted by quarantine camps, often lacking proper living and food conditions. As a result, the Sultan was forced to issue a special decree forbidding the highlanders from selling their children and wives, who attempted, by this means, to save their loved ones from starving to death in the camps.

Thus, the Turkish monarch sought to enforce quarantine measures - too many Turks, hearing about the opportunity to buy "live goods" cheaply, rushed to the camps on the coast.

Finally, seeing the full horror of the situation, in 1867, the Caucasian viceroy, Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich, visiting the Kuban region, "personally informed the highlanders that their relocation to Turkey should cease definitively." However, even after this, there were those who, unwilling to give up on the "Turkish dream," became muhajirs.

The Remnants

As a result of the tragedy known in history as "muhajirism," only a small part of the once numerous Circassian people remained in their homeland. However, their fate turned out to be quite fortunate.

The princes integrated into the ranks of the Russian aristocracy, and common people gained the opportunity for peaceful work under the protection of strong authority. No one encroached upon the religion, traditions, or self-government of the highlanders. Soon, their relations with the Kuban Cossacks became very friendly.

The new Russian subjects received a number of privileges, including exemption from certain taxes and military service.

A number of gymnasiums were established in southern Russia, such as the Stavropol and Yekaterinodar Gymnasiums, where boarding schools for the children of the mountaineers were opened. At the Stavropol Gymnasium, the quota for the Circassians was 65 people, and at the Yekaterinodar Gymnasium, it was 25.

By official order, places were reserved for Circassian children in schools of large Cossack settlements, such as Pavlovskaya and Umanskaya.

In 1859, Emperor Alexander II approved a special Charter for Mountain Schools. According to it, the goal of the schools was "to spread civility and education among the subdued peaceful highlanders and to provide means for officers and officials serving in the Caucasus to raise and educate their children."

A circular from the Ministry of Education in 1867 stated that "gradually educating the foreign peoples, bringing them closer to the Russian spirit and to Russia, constitutes a task of the greatest political importance."

After finishing these schools, young Circassian men had the right to enter higher military schools, from which they graduated as officers and went on to serve in the army. A certain number of Adyghes also entered the best civilian universities in the country.

For example, the Adyghe Shumaf Tatlok graduated from Moscow University in 1859, became a candidate of law, and was retained for work in Moscow. This same university was also attended by the well-known public figure of Kabarda, L. M. Kodzokov, and other Adyghe educators, such as Kazi Atazhukin, Adil-Giray Kesev, and Sultan Krym-Giray Inatov, studied at St. Petersburg University.

At the same time, several individuals began to create the Adyghe alphabet. Even before the end of the Caucasian War, the Circassians had their own writers, doctors, teachers, historians, philologists, and mathematicians. They enlightened the people, gave them their own Adyghe alphabet, treated them, and wrote their history. The ethnographer Leonid Yakovlevich Lyulye developed the "Circassian Lexicon with a Brief Grammar," which was published in 1846, where he presented his version of the Adyghe alphabet.

And it must be said, the Adyghes responded with true loyalty. Circassian volunteers participated in all subsequent wars of the empire, earning undying glory.

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, a large militia of Adyghes fought in the Russian army. In addition to other units and regiments, the Kabardino-Gorsk and Kabardino-Kumyksky cavalry irregular regiments were formed on the Terek, mainly consisting of Kabardins, and on the Kuban — the Kuban-Gorsk cavalry irregular regiments, the Labinsky Squadron, and so on.

During this period, the Kabardian nobleman, Colonel (who became a Major General in 1890) Altadukov Tepsaruko Khamurzanovich (also Altudokov Tepsoruko Khadzhimurzovich), commander of the 2nd Mountain-Mozdok Cavalry Regiment of the Tersk Cossack Army, was awarded the Order of St. George 4th Class on June 9, 1878, "for distinguished service in actions against the Turks during the capture of the enemy position at Deivo-Boynu on October 23, 1877."

Another Kabardian, Colonel (who became a Lieutenant General in 1892) Shipchev Temirkhan Aktolovich (1830-1904), who commanded a regiment of the Kuban Cossack Army, was awarded the Order of St. George 4th Class on March 24, 1880, "for outstanding military feats displayed on July 24, 1877, near the village of Khalfaly."

Altadukov and Shipchev, for their distinction in this war, were also awarded the Gold Weapon with the inscription "For Bravery" (since 1913, the Georgievskoye weapon).

The following fact testifies to the role the highlanders played in the Armed Forces of the Empire: it was customary for Muslim cavalrymen and Orthodox commanders to exchange Easter greetings, and vice versa.

The long-standing cooperation between Muslims and Orthodox Christians in the Imperial Army led to customs that did not infringe upon either side. For example, one of the duties of the adjutant of the Kabardian Cavalry Regiment during communal lunches and dinners in the officers' mess was to count how many Muslims and how many Christians were present.

If Muslims made up the majority at the table, everyone remained in their papakhas (traditional hats), but if Christians were the majority, the papakhas were removed (according to Kabardian custom, the officers of the regiment always wore papakhas at home and only removed them when going to bed).

This approach shows an understanding and respect for the traditions of different nationalities and cultures. Religious differences and the multiethnic nature of the military contingents did not cause any conflicts within the ranks of the Russian Imperial Army.

During the Great Patriotic War, 20 sons of the Adyghe people were honored with the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. This small yet remarkable people of Russia has produced many outstanding scientists, writers, composers, and athletes.

Since the 1920s, there have been mountain autonomous regions in the USSR. Newspapers, magazines, educational, literary, and journalistic works have been and continue to be published in Kabardian and Adyghe dialects. Television and radio broadcasts are conducted, and theaters are in operation. Numerous choreographic and vocal ensembles are active.

The language continues to be studied in scientific research and taught in educational institutions. There are no restrictions on its use.

"The Turks "accepted" us in a way I would not wish upon you"

The fate of the muhajirs unfolded quite differently. Some, like Musa Kundukhov, easily integrated into the Turkish elite, but they were the exception. The rest were treated by the Turks as cannon fodder and cheap labor. The most significant hardship, however, was the forced assimilation they endured.

Shinkuba describes this process in detail: the Ubykhs changed their names and surnames, women were no longer allowed to attend celebrations or gatherings, and they were forced to wear the chador.

The Turkish aristocracy quickly renounced their people, their customs, and their native language. The people were left to fend for themselves and faced many hardships. Over time, the younger generation forgot the language, the goddess Bytha was taken, and there were no more priests.

Shinkuba contrasts two paths: the Abkhaz, unwilling to shift their allegiance between rulers, chose the White Tsar and never wavered from that decision. The Ubykh leader, initially accepting a rank and stipend from the Tsar, eventually defected to the Turks, bringing along the clans under his command. By the end of the 19th century, neither the Abkhaz nor the Ubykhs had a written language.

However, the Abkhaz managed to acquire one and preserved their language. The few attempts by the enthusiast Tagir to teach Ubykh children in their native language were suppressed, and the handwritten alphabet was destroyed. Other advocates for the language also failed in their efforts.

The Tragic "Fortune"

However, the Ubykhs did not physically disappear. It was their language that vanished. Their descendants switched to Turkish, although many of them still retain memories of their Ubykh roots.

In Turkey, there are several villages on the coast of the Sea of Marmara where Turks — descendants of the Ubykhs — live. Some of them know their genealogy. However, despite this knowledge, their mentality is completely different now — Turkish.

Today, propagandists attempting to play the "Circassian card" against Russia accuse our country of the total destruction of the Ubykhs. But the reality is that this ethnic group, in fact, (compared to other Adyghe tribes) almost never fought against Russia, with the exception of a few attacks on the forts of the Coastal Line.

Apart from two or three small operations carried out by the Russians from the territory of Abkhazia and a few coastal fortresses, the Russian soldier set foot on the land of this tribe only in 1864, in the final days of the war.

On March 4th, General Geyman sends a letter to the Ubykh elders with an ultimatum of resettlement either to Turkey or to Kuban. On March 9th, the Ubykhs respond, declaring their surrender and requesting three months to resettle to Turkey. The unit continued its movement eastward.

On March 18th, near the mouth of a small river, Ghodlik, a relatively large battle occurs with a group of rebellious Ubykhs and other small tribes. Russian forces quickly defeat the mountain dwellers, and Ubykhs no longer take part in military actions nor are subjected to any reprisals.

Due to this, the Ubykhs — unlike other Circassian tribes — were able to preserve their organization, order, and governance up to the very end and even after surrender.

While other Circassian communities, misled by their nobility and Turkish agitators, fled in disarray to the Black Sea ports and harbors for departure to Turkey (which largely caused the tragedy of 1864 and the massive losses of Adyghe during resettlement), the Ubykhs maintained order, organized ship rentals, and obeyed their leaders' will, departing peacefully within two weeks without any losses — neither of infants nor of the elderly.

The most significant aspect is that the Ubykhs were the only Adyghe ethnic group to emigrate to Turkey almost in its entirety. A total of 74,500 Ubykhs left, while only a few dozen of this tribe remained on the homeland.

Thus, the tribe, which suffered least during the Caucasian War and managed to emigrate without losses, disappeared completely, becoming assimilated, losing its language and culture, while the ethnic groups who remained "under the heel of the conquerors" were able to preserve their language, traditions, and develop their culture. Bagrat Shinkuba conveys all of this with utmost accuracy.

An even more succinct Abkhaz proverb sums it up: "He who loses his homeland loses all."

The irreconcilable Circassians became a losing card in the underhanded game between Turkey and Great Britain, which ultimately led to their greatest tragedy — the loss of their identity, national self-awareness, and culture.

However, today the "Circassian card" is once again being used against Russia.

Now, alongside Turkey, the USA, the EU, Georgia, and even Israel are involved. To this end, dishonest speculations about historical events that occurred 160 years ago are being spread. The enemies of our country are doing everything they can to drive a wedge between the Adyghe peoples and their neighbors, creating a new point of tension in the Caucasus.

Last edited: