After President Donald Trump banned transgender girls from competing in girls’ sports, a Virginia high-schooler joined the boys’ team.

Eliza Munshi waits in line to throw the discus at a district track meet March 19 in Falls Church, Virginia. (Allison Robbert/For The Washington Post)

By Karina Elwood

April 3, 2025

Eliza Munshi kneeled on her bedroom floor curling her lashes. She dabbed glitter into the corners of her eyes and debated whether to tie her hair into one French braid or two. She slipped on her green jersey and headed to her first track and field meet.

At Falls Church High School, she waited for a practice throw in the discus event, taking her place in a line of boys. Runners passed by on the track. Coaches hovered nearby. Eliza was nervous, but in the way that any teen might be before their first competition in a new sport.

This wasn’t how Eliza imagined it would go when she tried out for track in February.

But that month, President Donald Trump signed an executive order banning transgender girls like Eliza from competing on girls’ and women’s sports teams. Days later, the organization that regulates high school sports in Virginia, where Eliza lives and goes to school, followed suit.

She could no longer compete with the girls.

Until recently, being transgender had posed few challenges for Eliza. She has supportive parents and friends, and she receives gender-affirming care. But in recent years, transgender rights, particularly for young people, have become a political target for conservative leaders. Trump leaned into anti-transgender messaging in the final weeks of his campaign. It has left families such as Eliza’s feeling the effects of one of the country’s most contentious debates, even here in liberal-leaning Fairfax County.

Public sentiment on the topic is changing, and nuanced. Polling has shown a majority of Americans support laws prohibiting discrimination against trans people, including in K-12 schools. But it also has shown most Americans believe transgender girls shouldn’t be allowed to play on girls’ teams.

Eliza, 18, had avoided playing sports in high school because she knew the process to join a team would be more difficult for her. This season was her last chance to join her friends and participate before she graduates in June.

She wasn’t going to let the president’s executive order stop her. So when it was finally her turn at the meet, Eliza stepped into the circle as part of the boys’ team. She wound up and let the discus fly.

For as long as she can remember, Eliza knew she was a girl.

Her parents tell stories of Eliza still in diapers crawling around the house with her hands slipped into her mother’s peacock-print wedges. When she was old enough to walk, she’d clop around in her own plastic princess heels, twirling in fairy dresses.

At bedtime, as her dad flipped through storybooks, Eliza would point to the princess or the mom in the book and say, “That’s me.” After about a dozen times of correcting her, her dad, Shyam, realized that maybe his daughter was right. Maybe that was who she really was.

Eliza in childhood. (Family Photo)

In her room at her home in Fairfax County, Eliza holds the red slippers she wore as a child until they wore out. (Allison Robbert/For The Washington Post)

In kindergarten, Eliza wanted to dress in “boy” clothes, but paired with a fairy lunch box and glittery red flats. There were so many times that Eliza’s mom, Ali, wanted to tell her child not to wear the red shoes to school.

But she believed the right thing to do was to let Eliza be herself. So she confidently walked to school with Eliza, who wore the red slippers until the toes tattered. And when Ali left, she cried. She knew how mean kids could be.

Ali and Shyam worked to remove any obstacle they could. When Eliza changed her name and pronouns during the summer between fourth and fifth grade, Ali sent an email to their family and friends informing them of the change. She made a point to call ahead to dentist offices and to brief teachers.

Together her parents combed through countless articles to find the best ways to support their child. They joined support groups and consulted medical professionals. When Eliza eventually began gender-affirming care, they took things slowly, relying on medical evidence and research for each decision.

Like any parents, they wanted Eliza to have what she needed to thrive, but they also wanted her to be safe.

In the early days of Eliza’s transition, Northern Virginia was a welcoming place to do that. In Fairfax County, their friends, schools and community were widely supportive of Eliza — and excited for her.

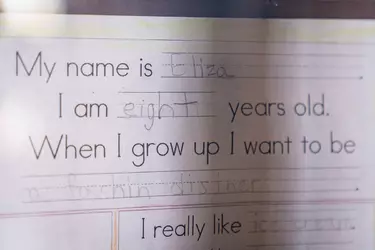

A worksheet completed by Eliza. (Allison Robbert/For The Washington Post)

At the time, transgender rights didn’t have the political firepower they do today. Many states and sports associations allowed trans athletes to compete on boys’ and girls’ teams. In 2014, when Eliza was in first grade, the Virginia High School League implemented a process that gave transgender students across the state a route to play on teams matching their gender identity.

But in the eight years since Eliza transitioned, trans people, who represent less than 1 percent of the country’s population, became more visible. And with that came more talk about trans rights — from people looking to protect and attack them.

As this was happening, Eliza’s family was moving. Her father is in the military, so they bounced around — Germany, Los Angeles, Ohio, Virginia. When they moved to Alabama shortly after Eliza transitioned, and then Florida, they made the decision to limit who knew.

When she arrived at a new school, she was welcomed as a girl because that’s all anyone knew her to be. Only Eliza’s closest friends knew she was transgender.

But in the two years they were in Florida, the backlash to trans rights intensified. Across the country in 2023, more bills targeting transgender rights were introduced and passed than at any other time in U.S. history. That included a law in Florida banning gender-affirming care for minors (a judge struck down the law last year).

Shortly after the law passed, Eliza’s doctor called.

“I can no longer have Eliza as my patient,” the doctor told her mother.

The family knew they needed to leave. That summer, they packed up again and returned to Northern Virginia.

At the track meet after school, Eliza giggled with her friends, talking about classes and colleges. She cheered for teammates on the girls’ team throwing shot put. In many track and field events, athletes compete individually. Meets and practice are also coed, which simplified the jump from the girls’ to boys’ team for Eliza. It wouldn’t have been as easy in other sports.

Eliza talks with her father before her second discus throw at the meet March 19. (Allison Robbert/For The Washington Post)

Her dad floated around behind her, keeping his eyes peeled for anyone who might give his daughter a hard time.

Just before the sun began to set, Eliza was finally up to throw. Behind the net, a row of friends and teammates cheered her on.

She rocked back and forth, then flung the discus into the air.

It landed 43 feet and 2 inches from the circle. The average throw in the boys’ competition that day was about 74½ feet.

On her second throw, Eliza decided to spin. She got into position and quickly twisted around using her body’s momentum to help the discus sail.

This time, it landed at 41 feet and 4 inches.

Returning to Virginia just before junior year gave Eliza a chance to be open. Many of the students at Falls Church High School had known Eliza in elementary school before she transitioned. She added the transgender flag emoji to her Instagram bio and didn’t make any effort to hide her identity.

She quickly made friends and continued living as a typical teenage girl. She joined theater and taught her friends to ski on weekends. She listens to Taylor Swift and dyes the ends of her hair pink. She plans to take a gap year after graduating before going to college to study education.

At first, the rising policies against trans youth didn’t seem to affect Eliza. Despite efforts from Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin (R) to restrict transgender rights in schools, the Fairfax County district has maintained its policy allowing students to use the pronouns and facilities that match their identity. In a statement, the school district said it follows state and federal laws to allow student-athletes to participate in athletics as they choose.

Eliza says everyone at the school — from teachers to coaches — has made her feel welcome, even through the policy changes.

“Sometimes I forget I’m transgender,” Eliza wrote in her college admissions essay this fall. “People around me forget too.”

Eliza on March 18. (Allison Robbert/For The Washington Post)

Sports was always an exception to that. At one point, Eliza wanted to join the volleyball team, but she worried about the process of proving she should play with the girls. At the time, the Virginia High School League policy would have required her to submit records from her doctors and letters from family and friends. She’d have to get approval from her school’s principal, then it would all go before a board to determine whether she could join a girls’ team.

Eliza, like many other transgender kids, largely avoided sports for that reason.

But recently, Eliza had seen the headlines about the increasing number of states banning trans girls from girls’ sports. Most recently, she’d seen Trump’s executive order titled “Keeping Men Out of Women’s Sports.”

She also saw that the Virginia High School League had initially said it would maintain its policy allowing transgender students to use the appeals process to play.

She decided to give sports a shot. Sitting around the lunch table, her friends convinced Eliza she could quickly learn how to throw shot put and discus. They promised to help her along the way.

It was a chance to try something new, she said, spend time with her friends and squeeze some exercise into her week.

It was also a chance, she thought, to prove that it wasn’t as easy as everyone seemed to think it was for transgender girls in Virginia to compete in sports.

So, Eliza marched into the athletics office in February.

“I’m transgender,” she said. “Can I start an appeal?”

Eliza puts on her competition shoes ahead of her event at the meet March 19. (Allison Robbert/For The Washington Post)

In February, Eliza joined the girls’ track team. During her fourth practice, when she was just beginning to get the hang of the discus and shot put, her phone rang.

Her mom explained that Eliza’s paperwork had been flagged after her doctor filled in “male” with “assigned at birth” scribbled next to the checked box. Eliza knew this would happen. She had no intention of hiding that she was transgender and was prepared for the lengthy appeals process.

But her mom explained that things had changed. The league, to comply with the executive order, revoked the option for trans girls to play on girls’ teams.

It was no longer merely difficult for Eliza to prove that she should compete with the girls. It was impossible.

Most high school athletes don’t go on to play competitively in college or professional sports. They play for the benefits of learning teamwork, discipline and community.

Yet, trans athletes are rare. In Virginia, only 31 athletes have petitioned to play since 2020. Twenty-eight were approved. But those supporting bans believe transgender girls have an unfair advantage over cisgender girls. And public support for that sentiment is growing. A 2022 Washington Post-KFF poll found that two-thirds of Americans agreed that trans girls should not be allowed to play girls’ high school sports.

Eliza practices her discus throw with teammate Zach at Falls Church High School on March 22. (Allison Robbert/For The Washington Post)

Eliza couldn’t help but think that if more people saw trans girls like her, they might think differently. She never went through male puberty, starting blockers before her body began making high levels of testosterone — the hormone that causes boys to typically be more muscular, grow facial hair and develop deeper voices.

If she competed with the girls, Eliza knew there would be consequences.

According to league policy, if a school knowingly allows a student who has been deemed ineligible to play, the school could be disqualified from competing in the league. The penalties are determined based on each individual case.

She didn’t want to jeopardize her teammates. So Eliza walked over to her coach and said she’d be competing with the boys.

She didn’t think she had an advantage against the girls. She certainly wouldn’t have one over the boys, most of whom are bigger than she is. In fact, she knew it would be harder. The boys’ discus weighs about 3.5 pounds, almost a pound heavier than that of the girls. The boys’ shot is 12 pounds, and the girls’ is about 8.

For the next month, Eliza kept practicing. The Saturday before her first meet, she spent the afternoon at the track with a couple of teammates. She threw the discus over and over.

“You’re folding like a lawn chair!” her friend Zach yelled out. He corrected her form and fixed her foot placement.

Eliza makes her second discus throw at the meet March 19. (Allison Robbert/For The Washington Post)

At the meet last month, Eliza stepped into the circle for her third and final throw.

She wound up, gracefully spinning around in the dancelike movement she had practiced hundreds of times. Her feet planted and the disc flew, hitting the field with a thud.

Eliza turned to her friends with her mouth agape.

“That’s like my best one!” she exclaimed, as staff rolled out the tape measure.

The day had gone as well as she could have expected. She was surrounded by friends, teammates and coaches who wanted to see her succeed. No one seemed to pay mind to the fact that she stood out among the boys. After the throw, Shyam wrapped his daughter in his arms. The day had gone as smoothly as he could have hoped, too.

Forty-six feet and 10 inches.

It was one of her farthest throws yet — and the shortest in the boys’ competition that day.

Source (Archive)