Kunshiro Kiyozumi is a small man with gray hair and a stooped back who lives alone and still pedals his bicycle to the supermarket. At 97, he cuts an unprepossessing figure to the younger shoppers busy texting while filling their carts, unaware his life contains a dramatic story shaped by history’s deadliest war.

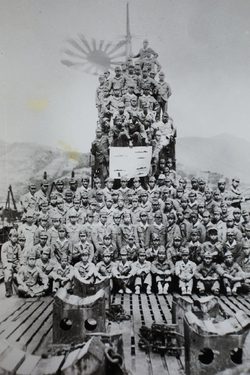

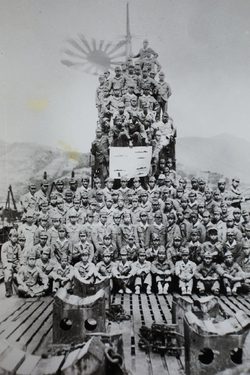

At age 15, Mr. Kiyozumi became the youngest sailor aboard the I-58, an attack submarine of the Imperial Japanese Navy. In the closing days of World War II, it prowled the Pacific Ocean, torpedoing six Allied ships, including the heavy cruiser U.S.S. Indianapolis, which it sank.

The Japanese I-58 submarine in Sasebo in 1946. The vessel torpedoed Allied ships and sank the U.S.S. Indianapolis.

Credit...PhotoQuest/Getty Images

He served in a military that committed atrocities in a march across Asia, as Japan fought in a brutal global conflict that was brought to an end with the atomic bombings of two of its cities. All told, World War II killed at least 60 million people worldwide.

But the living veterans like Mr. Kiyozumi were not the admirals or generals who directed Japan’s imperial plans. They were young sailors and foot soldiers in a war that was not of their making. Most were still in their midteens when they were sent to far-flung battlefields from India to the South Pacific, where some were abandoned in jungles to starve or left bearing dark secrets when the empire fell.

After Japan surrendered on Aug. 15, 1945, they returned to a defeated nation that showed little interest in their sacrifices, eager to put aside both painful memories and uncomfortable questions about its wartime aggression. Mr. Kiyozumi lived a quiet life, working at a utility company installing the electrical wires that helped power Japan’s reconstruction. Over time, his former crewmates died, but he rarely spoke about his wartime experiences.

Kunshiro Kiyozumi on his way to a restaurant for lunch in Matsuyama. He was the youngest crew member of the Japanese Imperial Navy submarine I-58.

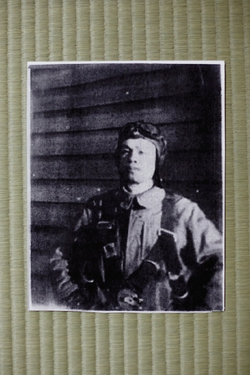

“I am the last one left,” Mr. Kiyozumi said in his home, showing fading photographs of the sub and himself as a young sailor.

As the 80th anniversary of the war’s end approaches, the number of veterans still alive is rapidly dwindling. There were only 792 Japanese war veterans still collecting government pensions as of March, half the number of a year earlier.

Now in their upper 90s and 100s, they will take with them the last living memories of horrors and ordeals, but also of bravery and sacrifice — powerful accounts that hold extra meaning now, as Japan builds up its military after decades of pacifism. Here are some of their stories.

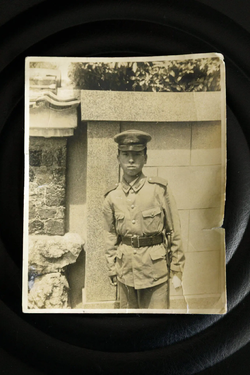

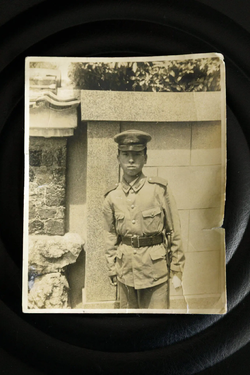

Kenichi Ozaki at his home. And at age 15, when he enlisted.

Kenichi Ozaki was 15 when he enlisted in 1943, as most young men were expected to do as the tide of war turned against Japan. Told that it was a righteous cause, he joined the Imperial Army out of middle school in rural western Japan over his parents’ objections.

Less than halfway through his training to become a radio operator, Mr. Ozaki was rushed to the Philippines, where the Americans had arrived to try to reclaim their former colony from the Japanese. Poorly equipped and ill-prepared, the Japanese force was quickly routed.

U.S. troops taking aim at Japanese positions on Leyte island in the Philippines in 1944.

Credit...Keystone/Getty Images

The demoralized survivors fled into the jungle, where they wandered for months. Mr. Ozaki watched those around him fall from attacks by Philippine guerrillas or starvation. While he survived on leaves and stolen crops, Mr. Ozaki saw soldiers eat what appeared to be the bodies of dead comrades.

After the war he returned to Japan, where he made a career at a company making electrical parts, rising to executive. For half a century, he didn’t speak of the war. He broke his silence when he realized how few people knew what his fallen comrades had endured.

Mr. Ozaki now does day trading from his home in Kyoto.

Now 97, Mr. Ozaki still dreams of those left behind, told they were dying for the glory of the empire, but sent into combat with no hope of victory.

“In their last breaths, no one shouted for the long life of the Emperor,” said Mr. Ozaki, who lives in Kyoto with his son, also retired. “They called out for their mothers, whom they would never see again.”

Hideo Shimizu was part of the secretive Unit 731 of the Japanese army, which he was told never to speak about after the war.

For more than 70 years, Hideo Shimizu kept silent about the horrors that he experienced.

Born in the village of Miyata in mountainous central Japan, he didn’t know much about the war when he was forced to enlist in a youth brigade in 1945 at the age of 14. Because he was dexterous, a teacher recommended him for a special assignment.

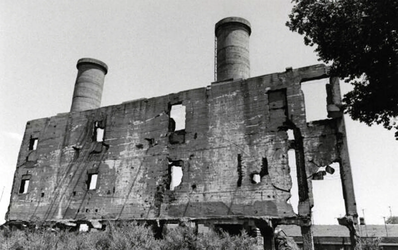

After days of travel by ship and train, Mr. Shimizu arrived in Harbin in Japanese-controlled Manchuria, where he learned he would be joining Unit 731, a secretive group developing new weapons.

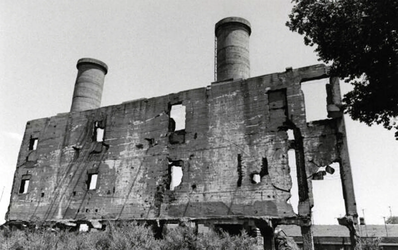

All that remained of Unit 731 near Harbin after the war. It was a covert biological and chemical warfare facility that experimented on humans.

Credit...Universal Images Group via Getty Images

At first, Mr. Shimizu dissected rats. Then he was taken to see the unit’s real experiments. He never forgot the sight: Chinese civilians and captured Allied soldiers preserved in formaldehyde, their bodies flayed open or cut into pieces. They had been infected with bacteria and dissected alive to see the effects on living tissue.

When the war ended, his unit escaped the advancing Soviets by rushing back to Japan, where he was told never to speak again about their work. Despite constant nightmares, Mr. Shimizu obeyed as he started a new life running a small construction company.

Mr. Shimizu at his home in Miyata. For decades after the war ended, he followed orders keep quiet about the horrors that he’d seen.

In 2015, he accompanied a relative to a museum where a photograph of Unit 731’s base was displayed. When he started explaining the buildings in detail, the museum’s curator happened to overhear, and persuaded him to speak in public.

Now 95 years old, Mr. Shimizu tries to combat the denials proliferating online about atrocities committed by Unit 731.

“Only the very youngest of us are left,” Mr. Shimizu said. “When we are gone, will people forget the terrible things that happened?”

Tetsuo Sato with his daughter-in-law, Kuniko. Mr. Sato belonged to the 58th Infantry Regiment of the 31st Division.

Sitting in the living room of his wooden home in the rice-growing village of Osonogo in mountainous Niigata Prefecture, Tetsuo Sato, 105, still seethes with anger over a battle fought long ago.

After growing up as one of 12 children who didn’t always have enough to eat, Mr. Sato left this village in 1940 to join the army. He ended up in Japanese-occupied Burma (now Myanmar) just as Japan was planning an offensive against the city of Imphal, across a mountain range in British-ruled India.

Mr. Sato at home in Osonogo, a village in Japan’s northern prefecture of Niigata.

Proclaiming that their soldier’s fighting spirit would prevail, the Japanese generals sent them without adequate weapons or supply lines, ordering them never to retreat. At first, the enemy troops appeared to flee, but it was a trap. When the British surrounded them, Mr. Sato escaped only because his commander disobeyed the orders and pulled back.

Even then, many died from starvation and disease as they fled back to Burma.

“They wasted our lives like pieces of scrap paper,” Mr. Sato said. “Never die for Emperor or country.”

A photo of Japanese Emperor Hirohito at Mr. Sato’s home. “Never die for Emperor or country,” he said.

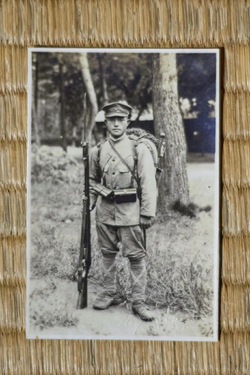

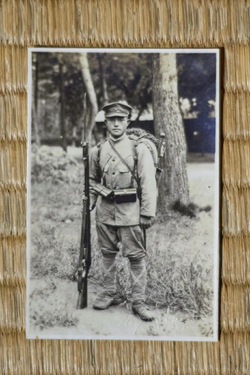

Tadanori Suzuzki at 96, and when he was photographed at 16.

Tadanori Suzuki was also keen to help his country when he enlisted in the Imperial Navy at age 14. He regretted it right away when the officers regularly struck the new recruits. The beatings stopped only when he was sent to the tropical island of Sulawesi, now in Indonesia, which the Japanese had seized from the Dutch.

Explosions at Japanese facilities on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia in 1942.Credit...US Navy/Interim Archives/Getty Images

There, he trained on a small torpedo boat, spending sleepy weeks in the heat and tasting bananas for the first time. The idyll ended when a U.S. destroyer was spotted.

His boat was one of eight sent to intercept it. As they sped toward the gray enemy vessel, Mr. Suzuki heard the “bam-bam-bam” of its guns. When he pulled a lever to launch a torpedo, he saw a pillar of flame rise from the American ship. “A hit! A hit!” he yelled. But three of the Japanese boats never returned.

Lacking fuel and ammunition, his squadron never forayed out again. Captured at the war’s end, it took him six months to get home. When he knocked on his door, his mother burst into tears. “I thought you were dead,” she said, then prepared him a bath.

Mr. Suzuki, who became a carpenter after the war, at his home in Tokyo. Now he warns school students not to go to war.

After retiring from his job as a carpenter, he started speaking to elementary schools near his home in Tokyo, warning them that there is no romanticism in war.

“I tell the younger generations, ‘A long time ago, we did something really stupid,’” says Mr. Suzuki, now 96. “Don’t go to war. Stay home with your parents and families.”

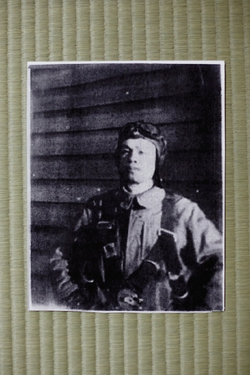

Masao Go was a radio operator on a bomber during the war.

One sunny April day, Masao Go, 97, was at a Buddhist temple near his home in Yokohama to watch placement of a stone with calligraphy etched into its face: “Taiwan our fatherland, Japan our motherland.”

Mr. Go was born in Taiwan when it was a Japanese colony. His parents sent him to school in Tokyo, where he learned to be a proud citizen of the Japanese empire. In 1944, he joined the Imperial Army, eager to fight for a cause that he embraced as his own.

Workers placing a memorial stone, engraved with “Taiwan our fatherland, Japan our motherland,” at Shinshoji Temple in Yokohama.

Trained as a radio operator on a bomber, he was assigned to an air base in Japanese-occupied Korea. His unit was told to prepare for a final attack against American forces on Okinawa, but Japan surrendered before the order came. Captured by Soviet troops, he was sent to a prison camp in Kazakhstan.

By the time of his release two years later, Taiwan was part of China. Mr. Go went instead to Japan, where he became a banker in Yokohama’s vibrant Chinatown.

After hiding his military service for years, he now talks about it, concerned that Japan and Taiwan face a new threat, this time from China seeking to expand its dominance in Asia. He erected the stone, which honors the 30,000 Taiwanese who died fighting for Japan in World War II, to remind Japan of its connection to Taiwan, now a self-governing island that China vows to reclaim by force.

“A threat to Taiwan is a threat to Japan,” Mr. Go said. “We are bound by history.”

Mr. Kiyozumi at his home. The crew of the submarine I-58 was known to have sunk the U.S.S. Indianapolis.

Mr. Kiyozumi, the youngest sailor aboard the I-58, still vividly remembers the day in July 1945 when the I-58’s lookouts spotted an approaching American warship. The submarine dove to fire its torpedoes. The captain watched through the periscope as the enemy vessel capsized and sank.

Years later, Mr. Kiyozumi learned their target had been the U.S.S. Indianapolis, which had just delivered parts of the atomic bombs to the island of Tinian for use against Japanese cities to end the war. Of the American ship’s 1,200 sailors, only 300 survived.

“It was war,” Mr. Kiyozumi said, expressing sorrow but not regret. “We killed hundreds of theirs, but they had just transported the atomic bomb.”

Mr. Kiyozumi at a restaurant in Matsuyama.

While Mr. Kiyozumi once corresponded with a survivor of the American warship, he feels forgotten and alone. His wife died three decades ago; his best friend on the I-58 died in 2020. No one in his town asks about the war.

“Young people don’t know what we went through,” he said. “They are more interested in their smartphones.”

Article Link

Archive

At age 15, Mr. Kiyozumi became the youngest sailor aboard the I-58, an attack submarine of the Imperial Japanese Navy. In the closing days of World War II, it prowled the Pacific Ocean, torpedoing six Allied ships, including the heavy cruiser U.S.S. Indianapolis, which it sank.

The Japanese I-58 submarine in Sasebo in 1946. The vessel torpedoed Allied ships and sank the U.S.S. Indianapolis.

Credit...PhotoQuest/Getty Images

He served in a military that committed atrocities in a march across Asia, as Japan fought in a brutal global conflict that was brought to an end with the atomic bombings of two of its cities. All told, World War II killed at least 60 million people worldwide.

But the living veterans like Mr. Kiyozumi were not the admirals or generals who directed Japan’s imperial plans. They were young sailors and foot soldiers in a war that was not of their making. Most were still in their midteens when they were sent to far-flung battlefields from India to the South Pacific, where some were abandoned in jungles to starve or left bearing dark secrets when the empire fell.

After Japan surrendered on Aug. 15, 1945, they returned to a defeated nation that showed little interest in their sacrifices, eager to put aside both painful memories and uncomfortable questions about its wartime aggression. Mr. Kiyozumi lived a quiet life, working at a utility company installing the electrical wires that helped power Japan’s reconstruction. Over time, his former crewmates died, but he rarely spoke about his wartime experiences.

Kunshiro Kiyozumi on his way to a restaurant for lunch in Matsuyama. He was the youngest crew member of the Japanese Imperial Navy submarine I-58.

“I am the last one left,” Mr. Kiyozumi said in his home, showing fading photographs of the sub and himself as a young sailor.

As the 80th anniversary of the war’s end approaches, the number of veterans still alive is rapidly dwindling. There were only 792 Japanese war veterans still collecting government pensions as of March, half the number of a year earlier.

Now in their upper 90s and 100s, they will take with them the last living memories of horrors and ordeals, but also of bravery and sacrifice — powerful accounts that hold extra meaning now, as Japan builds up its military after decades of pacifism. Here are some of their stories.

Starved in the Jungle

Kenichi Ozaki at his home. And at age 15, when he enlisted.

Kenichi Ozaki was 15 when he enlisted in 1943, as most young men were expected to do as the tide of war turned against Japan. Told that it was a righteous cause, he joined the Imperial Army out of middle school in rural western Japan over his parents’ objections.

Less than halfway through his training to become a radio operator, Mr. Ozaki was rushed to the Philippines, where the Americans had arrived to try to reclaim their former colony from the Japanese. Poorly equipped and ill-prepared, the Japanese force was quickly routed.

U.S. troops taking aim at Japanese positions on Leyte island in the Philippines in 1944.

Credit...Keystone/Getty Images

The demoralized survivors fled into the jungle, where they wandered for months. Mr. Ozaki watched those around him fall from attacks by Philippine guerrillas or starvation. While he survived on leaves and stolen crops, Mr. Ozaki saw soldiers eat what appeared to be the bodies of dead comrades.

After the war he returned to Japan, where he made a career at a company making electrical parts, rising to executive. For half a century, he didn’t speak of the war. He broke his silence when he realized how few people knew what his fallen comrades had endured.

Mr. Ozaki now does day trading from his home in Kyoto.

Now 97, Mr. Ozaki still dreams of those left behind, told they were dying for the glory of the empire, but sent into combat with no hope of victory.

“In their last breaths, no one shouted for the long life of the Emperor,” said Mr. Ozaki, who lives in Kyoto with his son, also retired. “They called out for their mothers, whom they would never see again.”

Kept a Dark Secret

Hideo Shimizu was part of the secretive Unit 731 of the Japanese army, which he was told never to speak about after the war.

For more than 70 years, Hideo Shimizu kept silent about the horrors that he experienced.

Born in the village of Miyata in mountainous central Japan, he didn’t know much about the war when he was forced to enlist in a youth brigade in 1945 at the age of 14. Because he was dexterous, a teacher recommended him for a special assignment.

After days of travel by ship and train, Mr. Shimizu arrived in Harbin in Japanese-controlled Manchuria, where he learned he would be joining Unit 731, a secretive group developing new weapons.

All that remained of Unit 731 near Harbin after the war. It was a covert biological and chemical warfare facility that experimented on humans.

Credit...Universal Images Group via Getty Images

At first, Mr. Shimizu dissected rats. Then he was taken to see the unit’s real experiments. He never forgot the sight: Chinese civilians and captured Allied soldiers preserved in formaldehyde, their bodies flayed open or cut into pieces. They had been infected with bacteria and dissected alive to see the effects on living tissue.

When the war ended, his unit escaped the advancing Soviets by rushing back to Japan, where he was told never to speak again about their work. Despite constant nightmares, Mr. Shimizu obeyed as he started a new life running a small construction company.

Mr. Shimizu at his home in Miyata. For decades after the war ended, he followed orders keep quiet about the horrors that he’d seen.

In 2015, he accompanied a relative to a museum where a photograph of Unit 731’s base was displayed. When he started explaining the buildings in detail, the museum’s curator happened to overhear, and persuaded him to speak in public.

Now 95 years old, Mr. Shimizu tries to combat the denials proliferating online about atrocities committed by Unit 731.

“Only the very youngest of us are left,” Mr. Shimizu said. “When we are gone, will people forget the terrible things that happened?”

Marched into a Trap

Tetsuo Sato with his daughter-in-law, Kuniko. Mr. Sato belonged to the 58th Infantry Regiment of the 31st Division.

Sitting in the living room of his wooden home in the rice-growing village of Osonogo in mountainous Niigata Prefecture, Tetsuo Sato, 105, still seethes with anger over a battle fought long ago.

After growing up as one of 12 children who didn’t always have enough to eat, Mr. Sato left this village in 1940 to join the army. He ended up in Japanese-occupied Burma (now Myanmar) just as Japan was planning an offensive against the city of Imphal, across a mountain range in British-ruled India.

Mr. Sato at home in Osonogo, a village in Japan’s northern prefecture of Niigata.

Proclaiming that their soldier’s fighting spirit would prevail, the Japanese generals sent them without adequate weapons or supply lines, ordering them never to retreat. At first, the enemy troops appeared to flee, but it was a trap. When the British surrounded them, Mr. Sato escaped only because his commander disobeyed the orders and pulled back.

Even then, many died from starvation and disease as they fled back to Burma.

“They wasted our lives like pieces of scrap paper,” Mr. Sato said. “Never die for Emperor or country.”

A photo of Japanese Emperor Hirohito at Mr. Sato’s home. “Never die for Emperor or country,” he said.

Enlisted at 14

Tadanori Suzuzki at 96, and when he was photographed at 16.

Tadanori Suzuki was also keen to help his country when he enlisted in the Imperial Navy at age 14. He regretted it right away when the officers regularly struck the new recruits. The beatings stopped only when he was sent to the tropical island of Sulawesi, now in Indonesia, which the Japanese had seized from the Dutch.

Explosions at Japanese facilities on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia in 1942.Credit...US Navy/Interim Archives/Getty Images

There, he trained on a small torpedo boat, spending sleepy weeks in the heat and tasting bananas for the first time. The idyll ended when a U.S. destroyer was spotted.

His boat was one of eight sent to intercept it. As they sped toward the gray enemy vessel, Mr. Suzuki heard the “bam-bam-bam” of its guns. When he pulled a lever to launch a torpedo, he saw a pillar of flame rise from the American ship. “A hit! A hit!” he yelled. But three of the Japanese boats never returned.

Lacking fuel and ammunition, his squadron never forayed out again. Captured at the war’s end, it took him six months to get home. When he knocked on his door, his mother burst into tears. “I thought you were dead,” she said, then prepared him a bath.

Mr. Suzuki, who became a carpenter after the war, at his home in Tokyo. Now he warns school students not to go to war.

After retiring from his job as a carpenter, he started speaking to elementary schools near his home in Tokyo, warning them that there is no romanticism in war.

“I tell the younger generations, ‘A long time ago, we did something really stupid,’” says Mr. Suzuki, now 96. “Don’t go to war. Stay home with your parents and families.”

Fought for the Empire

Masao Go was a radio operator on a bomber during the war.

One sunny April day, Masao Go, 97, was at a Buddhist temple near his home in Yokohama to watch placement of a stone with calligraphy etched into its face: “Taiwan our fatherland, Japan our motherland.”

Mr. Go was born in Taiwan when it was a Japanese colony. His parents sent him to school in Tokyo, where he learned to be a proud citizen of the Japanese empire. In 1944, he joined the Imperial Army, eager to fight for a cause that he embraced as his own.

Workers placing a memorial stone, engraved with “Taiwan our fatherland, Japan our motherland,” at Shinshoji Temple in Yokohama.

Trained as a radio operator on a bomber, he was assigned to an air base in Japanese-occupied Korea. His unit was told to prepare for a final attack against American forces on Okinawa, but Japan surrendered before the order came. Captured by Soviet troops, he was sent to a prison camp in Kazakhstan.

By the time of his release two years later, Taiwan was part of China. Mr. Go went instead to Japan, where he became a banker in Yokohama’s vibrant Chinatown.

After hiding his military service for years, he now talks about it, concerned that Japan and Taiwan face a new threat, this time from China seeking to expand its dominance in Asia. He erected the stone, which honors the 30,000 Taiwanese who died fighting for Japan in World War II, to remind Japan of its connection to Taiwan, now a self-governing island that China vows to reclaim by force.

“A threat to Taiwan is a threat to Japan,” Mr. Go said. “We are bound by history.”

Forgotten by His Nation

Mr. Kiyozumi at his home. The crew of the submarine I-58 was known to have sunk the U.S.S. Indianapolis.

Mr. Kiyozumi, the youngest sailor aboard the I-58, still vividly remembers the day in July 1945 when the I-58’s lookouts spotted an approaching American warship. The submarine dove to fire its torpedoes. The captain watched through the periscope as the enemy vessel capsized and sank.

Years later, Mr. Kiyozumi learned their target had been the U.S.S. Indianapolis, which had just delivered parts of the atomic bombs to the island of Tinian for use against Japanese cities to end the war. Of the American ship’s 1,200 sailors, only 300 survived.

“It was war,” Mr. Kiyozumi said, expressing sorrow but not regret. “We killed hundreds of theirs, but they had just transported the atomic bomb.”

Mr. Kiyozumi at a restaurant in Matsuyama.

While Mr. Kiyozumi once corresponded with a survivor of the American warship, he feels forgotten and alone. His wife died three decades ago; his best friend on the I-58 died in 2020. No one in his town asks about the war.

“Young people don’t know what we went through,” he said. “They are more interested in their smartphones.”

Article Link

Archive