UN talks in disarray as a rough draft deal for climate cash is rejected by developing nations

Associated Press (archive.ph)

By Melina Walling, Seth Borenstein, Michael Phillis, and Sibi Arasu

2024-11-23 14:22:23GMT

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Saturday, Nov. 23, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — As nerves frayed and the clock ticked, negotiators from rich and poor nations were huddled in one room Saturday during overtime United Nations climate talks to try to hash out an elusive deal on money for developing countries to curb and adapt to climate change.

But the rough draft of a new proposal circulating in that room was getting soundly rejected, especially by African nations and small island states, according to messages relayed from inside. Then a group of negotiators from the Least Developed Countries bloc and the Alliance of Small Island States walked out because they didn’t want to engage with the rough draft.

The “current deal is unacceptable for us. We need to speak to other developing countries and decide what to do,” Evans Njewa, the chair of the LDC group, said. When asked if the walkout was a protest, Colombia environment minister Susana Mohamed told The Associated Press: “I would call this dissatisfaction, (we are) highly dissatisfied.”

With tensions high, climate activists heckled United States climate envoy John Podesta as he left the meeting room. They accused the U.S. of not paying its fair share and having “a legacy of burning up the planet.”

The last official draft on Friday pledged $250 billion annually by 2035, more than double the previous goal of $100 billion set 15 years ago but far short of the annual $1 trillion-plus that experts say is needed. The rough draft discussed on Saturday was for $300 billion in climate finance, sources told AP.

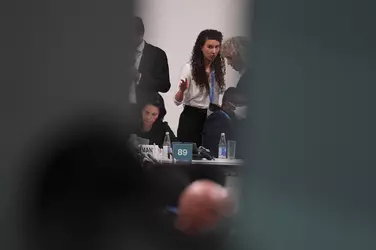

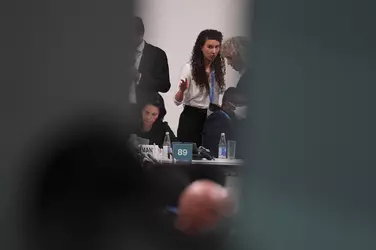

Jennifer Morgan, Germany climate envoy, right, and Joanna MacGregor, senior advisor for U.N. climate change, talk near Germany Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, bottom left, in a meeting room at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Saturday, Nov. 23, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Accusations of a war of attrition

Developing countries accused the rich of trying to get their way — and a small financial aid package — via a war of attrition. And small island nations, particularly vulnerable to climate change’s worsening impacts, accused the host country presidency of ignoring them for the entire two weeks.

After bidding one of his suitcase-lugging delegation colleagues goodbye and watching the contingent of about 20 enter the meeting room for the European Union, Panama chief negotiator Juan Carlos Monterrey Gomez had enough.

“Every minute that passes we are going to just keep getting weaker and weaker and weaker. They don’t have that issue. They have massive delegations,” Gomez said. “This is what they always do. They break us at the last minute. You know, they push it and push it and push it until our negotiators leave. Until we’re tired, until we’re delusional from not eating, from not sleeping.”

With developing nations’ ministers and delegation chiefs having to catch flights home, desperation sets in, said Power Shift Africa’s Mohamed Adow. “The risk is if developing countries don’t hold the line, they will likely be forced to compromise and accept a goal that doesn’t add up to get the job done,” he said.

Teresa Anderson, the global lead on climate justice at Action Aid, said that in order to get a deal, “the presidency has to put something far better on the table.”

“The U.S. in particular, and rich countries, need to do far more to to show that they’re willing for real money to come forward,” she said. “And if they don’t, then LDCs (Least Developed Countries) are unlikely to find that there’s anything here for them.”

An activists participates in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Saturday, Nov. 23, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

A climate cash deal is still elusive

Developing nations are seeking $1.3 trillion to help adapt to droughts, floods, rising seas and extreme heat, pay for losses and damages caused by extreme weather, and transition their energy systems away from planet-warming fossil fuels and toward clean energy. Wealthy nations are obligated to pay vulnerable countries under an agreement reached at these talks in Paris in 2015.

Panama’s Monterrey Gomez even the higher $300 billion figure that was discussed on Saturday is “still crumbs.”

“Is that even half of what we put forth?” he asked.

Monterrey Gomez said the developing world has since asked for finance deal of $500 billion up to 2030 — a shortened timeframe than the 2035 date. “We’re still yet to hear reaction from the developed side,” he said.

On Saturday morning, Irish environment minister Eamon Ryan said it’s not just about the number in the final deal, but “how do you get to $1.3 trillion.”

Ryan said that any number reached at the COP will have to be supplemented with other sources of finance, for example through a market for carbon emissions where polluters would pay to offset the carbon they spew.

The amount in any deal reached at COP negotiations — often considered a “core” — will then be mobilized or leveraged for greater climate spending. But much of that means loans for countries drowning in debt.

Anger and frustration over state of negotiations

Alden Meyer of the climate think tank E3G said it’s still up in the air whether a deal on finance will come out of Baku at all.

“It is still not out of the question that there could be an inability to close the gap on the finance issue,” he said.

Ali Mohamed, the chair of the African Group of Negotiators said the bloc “are prepared to reach agreement here in Baku ... but we are not prepared to accept things that cross our red lines.”

But despite the fractures between nations, several still held out hopes for the talks. “We remain optimistic,” said Nabeel Munir of Pakistan, who chairs one of the talks’ standing negotiating committees.

The Alliance of Small Island States said in a statement that they want to continue to engage in the talks, as long as the process is inclusive. “If this cannot be the case, it becomes very difficult for us to continue our involvement,” the statement said.

Panama’s Monterrey Gomez said there needs to be a deal.

“If we don’t get a deal I think it will be a fatal wound to this process, to the planet, to people,” he said.

___

Associated Press journalists Ahmed Hatem, Aleksandar Furtula and Joshua A. Bickel contributed to this report.

___

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Associated Press (archive.ph)

By Melina Walling, Seth Borenstein, Michael Phillis, and Sibi Arasu

2024-11-23 14:22:23GMT

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Saturday, Nov. 23, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — As nerves frayed and the clock ticked, negotiators from rich and poor nations were huddled in one room Saturday during overtime United Nations climate talks to try to hash out an elusive deal on money for developing countries to curb and adapt to climate change.

But the rough draft of a new proposal circulating in that room was getting soundly rejected, especially by African nations and small island states, according to messages relayed from inside. Then a group of negotiators from the Least Developed Countries bloc and the Alliance of Small Island States walked out because they didn’t want to engage with the rough draft.

The “current deal is unacceptable for us. We need to speak to other developing countries and decide what to do,” Evans Njewa, the chair of the LDC group, said. When asked if the walkout was a protest, Colombia environment minister Susana Mohamed told The Associated Press: “I would call this dissatisfaction, (we are) highly dissatisfied.”

With tensions high, climate activists heckled United States climate envoy John Podesta as he left the meeting room. They accused the U.S. of not paying its fair share and having “a legacy of burning up the planet.”

The last official draft on Friday pledged $250 billion annually by 2035, more than double the previous goal of $100 billion set 15 years ago but far short of the annual $1 trillion-plus that experts say is needed. The rough draft discussed on Saturday was for $300 billion in climate finance, sources told AP.

Jennifer Morgan, Germany climate envoy, right, and Joanna MacGregor, senior advisor for U.N. climate change, talk near Germany Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, bottom left, in a meeting room at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Saturday, Nov. 23, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Accusations of a war of attrition

Developing countries accused the rich of trying to get their way — and a small financial aid package — via a war of attrition. And small island nations, particularly vulnerable to climate change’s worsening impacts, accused the host country presidency of ignoring them for the entire two weeks.

After bidding one of his suitcase-lugging delegation colleagues goodbye and watching the contingent of about 20 enter the meeting room for the European Union, Panama chief negotiator Juan Carlos Monterrey Gomez had enough.

“Every minute that passes we are going to just keep getting weaker and weaker and weaker. They don’t have that issue. They have massive delegations,” Gomez said. “This is what they always do. They break us at the last minute. You know, they push it and push it and push it until our negotiators leave. Until we’re tired, until we’re delusional from not eating, from not sleeping.”

With developing nations’ ministers and delegation chiefs having to catch flights home, desperation sets in, said Power Shift Africa’s Mohamed Adow. “The risk is if developing countries don’t hold the line, they will likely be forced to compromise and accept a goal that doesn’t add up to get the job done,” he said.

Teresa Anderson, the global lead on climate justice at Action Aid, said that in order to get a deal, “the presidency has to put something far better on the table.”

“The U.S. in particular, and rich countries, need to do far more to to show that they’re willing for real money to come forward,” she said. “And if they don’t, then LDCs (Least Developed Countries) are unlikely to find that there’s anything here for them.”

An activists participates in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Saturday, Nov. 23, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

A climate cash deal is still elusive

Developing nations are seeking $1.3 trillion to help adapt to droughts, floods, rising seas and extreme heat, pay for losses and damages caused by extreme weather, and transition their energy systems away from planet-warming fossil fuels and toward clean energy. Wealthy nations are obligated to pay vulnerable countries under an agreement reached at these talks in Paris in 2015.

Panama’s Monterrey Gomez even the higher $300 billion figure that was discussed on Saturday is “still crumbs.”

“Is that even half of what we put forth?” he asked.

Monterrey Gomez said the developing world has since asked for finance deal of $500 billion up to 2030 — a shortened timeframe than the 2035 date. “We’re still yet to hear reaction from the developed side,” he said.

On Saturday morning, Irish environment minister Eamon Ryan said it’s not just about the number in the final deal, but “how do you get to $1.3 trillion.”

Ryan said that any number reached at the COP will have to be supplemented with other sources of finance, for example through a market for carbon emissions where polluters would pay to offset the carbon they spew.

The amount in any deal reached at COP negotiations — often considered a “core” — will then be mobilized or leveraged for greater climate spending. But much of that means loans for countries drowning in debt.

Anger and frustration over state of negotiations

Alden Meyer of the climate think tank E3G said it’s still up in the air whether a deal on finance will come out of Baku at all.

“It is still not out of the question that there could be an inability to close the gap on the finance issue,” he said.

Ali Mohamed, the chair of the African Group of Negotiators said the bloc “are prepared to reach agreement here in Baku ... but we are not prepared to accept things that cross our red lines.”

But despite the fractures between nations, several still held out hopes for the talks. “We remain optimistic,” said Nabeel Munir of Pakistan, who chairs one of the talks’ standing negotiating committees.

The Alliance of Small Island States said in a statement that they want to continue to engage in the talks, as long as the process is inclusive. “If this cannot be the case, it becomes very difficult for us to continue our involvement,” the statement said.

Panama’s Monterrey Gomez said there needs to be a deal.

“If we don’t get a deal I think it will be a fatal wound to this process, to the planet, to people,” he said.

___

Associated Press journalists Ahmed Hatem, Aleksandar Furtula and Joshua A. Bickel contributed to this report.

___

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.