- Joined

- Aug 24, 2014

By the time Myaskovsky was 60, in the year 1941, his health had gone considerably downwards. Just before his birthday he was admitted to a sanitorium for six weeks, and he subsequently stayed at Pavel Lamm's country house to recuperate. The restful period was cut short all of a sudden: the Nazis started bombing Moscow on 22 July 1941, and Lamm's house was in the flightpath. Lamm and Mysakovsky hurried back to Moscow for preparations. On 8 July, they were evacuated, being sent with a contingent of about 200 prominent musicians to Nalchik, Capital of what is today the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic. The journey through high altitudes, by camouflaged train, was grueling for most of the people, many of whom were more than 60 of age. Still, Myaskovsky at least found solace because he was travelling with one of his sisters, and many of his friends, such as Lamm and Prokofiev (who had returned to Russia for good in 1936). Prokofiev was happy as a clam: he had ditched his first wife earlier this year and had a new girlfriend in tow. Mira Mendelssohn, half of Prokofiev's age and who would become the second Mrs. Prokofiev, endeared herself to Myaskovsky and his sister immediately. She would leave behind some very poignant accounts of Myaskovsky's last days.

Life as an exile was hard. Lodgings were small, ill-furnished, lacking basic amenities, and Myaskovsky could not find the privacy he needed to compose. Money was always short. Fortunately, the director of Artistic Affair in Nalchik, Khatu Temirkanov (the father of the famous conductor Yuri Temikanov), seeing big-name composers among the exiles, offered them commissions: Prokofiev would write a string quartet; Myaskovsky a symphony. This was to be Myaskovsky's 23th, which Richard Taruskin breezily dismissed as "the rock bottom", seemingly unware or unconcerned about the difficulty of its genesis.

The misfortunes of war compelled the exiles to regular evacuation, first to Tbilisi, Georgia and then, through a thousand mile-long journey by rail and ferry, to Frunze (Bishkek), Kyrgyzstan. They were regularly given cold shoulders and terrible accommodations. The scene that await them at Frunze was particularly horrifying: dying people lined the streets, and beggars accosted them everywhere. Unsurprisingly, many exiles soon fell ill, and Myaskovsky tried to contact everybody he could so that at least he, his sister, and some close friends could be called back to Moscow. After many frustrations, his SOS call was answered, and they were back in Moscow in mid December 1942.

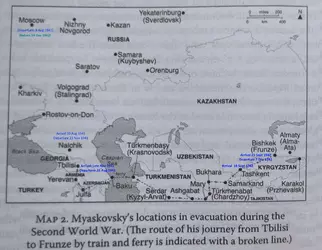

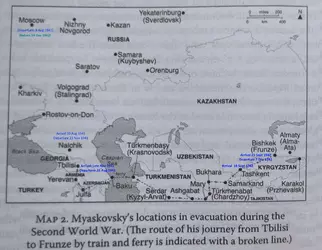

Here is the map from Patrick Zuk's book, with dates of arrivals and departures added in by myself.

In Frunze, Myaskovsky learned of the death of his close friend Vladimir Derzhanovsky. He and Myaskovsky had been friends since 1910. Derzhanovsky launched Myaskovsky's career, enabling his contact with prominent musicians, and as a proponent of Western music, Derzhanovsky organized concerts that allowed young composers in Moscow to keep abreast with the latest developments. He encouraged Myaskovsky to press on when the latter felt his grueling day job was driving him insane, and during WWI, Derzhanovsky's correspondence was the life-line to Myaskovsky, stationed in the West Front constantly bombarded by artillery. Despite being born in the same year as Myaskovsky (he was not conscripted in WWI for health reasons), Derzhanovsky's temperament, politics, and musical outlook differed from Myaskovsky's. After the October revolution, Derzhanovsky soon joined the Communist Party, and, ever enterprising, he seized opportunity to improve Moscow's musical culture, importing foreign books and music scores. Derzhanovsky's chief artistic concern was to challenge the hidebound musical culture of Tsarist Russia, and for him, foreign avant-garde like Debussy served this purpose just as well as Communist-approved, "proletarian" works. On Myaskovsky's part, he experience with the War had left him no illusion with the Tsarist regime, but he found the usurpers vulgar and unprincipled. Myaskovsky was skeptical about the virtue of foreign music (He was utterly unimpressed by Ravel, Poulenc, Martinu, Hindemith, and Krenek; but liked Debussy and pre-12 tone Schoenberg), and surely he had zero enthusiasm to write for the Party. Derzhanovsky would regularly suggest that Myaskovsky to write music "for the people", but he knew his friend too much to be pushy. In his final unsent letter to Myaskovsky, Derzhanovsky urged his friend to compose something to celebrate the inevitable defeat of Nazis at the hand of the Red Army, but acknowledge that his friend had always done his own thing, like Kipling's Cat That Walked By Himself.

Derzhanovsky's last days, as it subsequently transpired, was sheer tragedy. Through out the war he and his wife stayed at the outskirt of Moscow, and starvation and the lack of fuel aggravated his fragile health. He refused to send for help (and help might not be available at wartime: around the same time, another of Myaskovsky's friend, Dmitry Melkikh, suffered a stroke and was paralyzed on the left side. He was convinced he would soon die unattended, which turned out to be true). Derzhanovsky's wife called for his composer's colleagues in Moscow when her husband is moribund, but they -- Myaskovsky's students Mosolov and Shebalin -- arrived too late. Derzhanvosky's wife was with the corpse of her husband for four days. They buried him quickly, digging the grave by themselves.

Myaskovsky's Symphony 24 was dedicated to the memory of Derzhanovsky. What strikes me the most about this work is its economy. All three movement are made up of two to three long-breathed themes, being passed from one instrumental group to another and engaging in fugal treatments. Yet the ebb and flow of dynamics is so natural it is almost like breathing.

The symphony started with a brass fanfare, which was rather incongruent. In 1939, a young conductor of military wind band called Ivan Petrov befriended Myaskovsky, and given Myaskovsky's military background, Petrov's zeal in reforming the musical groups in the military impressed him, and that reignited Myaskovsky's interest in brass music. Petrov would become a solace to the old composer in his last dark years. The brass theme is soon passed to the strings, and subsequently being weaved into counterpoint.

The second movement is even more effective. Again the ingredients are similar: lyrical themes being weaved into counterpoint -- you can criticize the symphony on the ground that the counterpoints are too insistent, but recall Prokofiev's admonition to Myaskovsky about his First Symphony: "you are writing this counterpoint to please conservatoire teachers, when you should have let the theme shine on its own lyrical beauty!" But as a mature composer, Myaskovsky could have his cake and eat it too: the themes are given space to shine, and the counterpoint would please any academic. What is impressive about this movement is how the dynamics is organized: the music progresses like cascading, mounting waves. Patrick Zuk suggests that the symphony may recall the sound-world of Vaughan Williams, and I think this is especially true for the second movement. The final movement is again very brassy, but with a dark undertone of deep woodwinds. A triumphant mood gradually establishes, and transformed into a radiant serenity that ends the work.

The mood of the whole symphony is somewhat ambivalent: is it a farewell to a enterprising friend and benefactor? Myaskovsky is too complex to be subjected to simplistic narratives, a trap that people falls in when they hear the opening brass fanfare and deem the music as "social realist response to the war". The only thing we can do is to take the music on its own terms.

Derzhanovsky and Melkikh were hardly the only close person Myaskovsky lost during the war. His niece died giving birth to a stillborn child.

Life as an exile was hard. Lodgings were small, ill-furnished, lacking basic amenities, and Myaskovsky could not find the privacy he needed to compose. Money was always short. Fortunately, the director of Artistic Affair in Nalchik, Khatu Temirkanov (the father of the famous conductor Yuri Temikanov), seeing big-name composers among the exiles, offered them commissions: Prokofiev would write a string quartet; Myaskovsky a symphony. This was to be Myaskovsky's 23th, which Richard Taruskin breezily dismissed as "the rock bottom", seemingly unware or unconcerned about the difficulty of its genesis.

The misfortunes of war compelled the exiles to regular evacuation, first to Tbilisi, Georgia and then, through a thousand mile-long journey by rail and ferry, to Frunze (Bishkek), Kyrgyzstan. They were regularly given cold shoulders and terrible accommodations. The scene that await them at Frunze was particularly horrifying: dying people lined the streets, and beggars accosted them everywhere. Unsurprisingly, many exiles soon fell ill, and Myaskovsky tried to contact everybody he could so that at least he, his sister, and some close friends could be called back to Moscow. After many frustrations, his SOS call was answered, and they were back in Moscow in mid December 1942.

Here is the map from Patrick Zuk's book, with dates of arrivals and departures added in by myself.

In Frunze, Myaskovsky learned of the death of his close friend Vladimir Derzhanovsky. He and Myaskovsky had been friends since 1910. Derzhanovsky launched Myaskovsky's career, enabling his contact with prominent musicians, and as a proponent of Western music, Derzhanovsky organized concerts that allowed young composers in Moscow to keep abreast with the latest developments. He encouraged Myaskovsky to press on when the latter felt his grueling day job was driving him insane, and during WWI, Derzhanovsky's correspondence was the life-line to Myaskovsky, stationed in the West Front constantly bombarded by artillery. Despite being born in the same year as Myaskovsky (he was not conscripted in WWI for health reasons), Derzhanovsky's temperament, politics, and musical outlook differed from Myaskovsky's. After the October revolution, Derzhanovsky soon joined the Communist Party, and, ever enterprising, he seized opportunity to improve Moscow's musical culture, importing foreign books and music scores. Derzhanovsky's chief artistic concern was to challenge the hidebound musical culture of Tsarist Russia, and for him, foreign avant-garde like Debussy served this purpose just as well as Communist-approved, "proletarian" works. On Myaskovsky's part, he experience with the War had left him no illusion with the Tsarist regime, but he found the usurpers vulgar and unprincipled. Myaskovsky was skeptical about the virtue of foreign music (He was utterly unimpressed by Ravel, Poulenc, Martinu, Hindemith, and Krenek; but liked Debussy and pre-12 tone Schoenberg), and surely he had zero enthusiasm to write for the Party. Derzhanovsky would regularly suggest that Myaskovsky to write music "for the people", but he knew his friend too much to be pushy. In his final unsent letter to Myaskovsky, Derzhanovsky urged his friend to compose something to celebrate the inevitable defeat of Nazis at the hand of the Red Army, but acknowledge that his friend had always done his own thing, like Kipling's Cat That Walked By Himself.

Derzhanovsky's last days, as it subsequently transpired, was sheer tragedy. Through out the war he and his wife stayed at the outskirt of Moscow, and starvation and the lack of fuel aggravated his fragile health. He refused to send for help (and help might not be available at wartime: around the same time, another of Myaskovsky's friend, Dmitry Melkikh, suffered a stroke and was paralyzed on the left side. He was convinced he would soon die unattended, which turned out to be true). Derzhanovsky's wife called for his composer's colleagues in Moscow when her husband is moribund, but they -- Myaskovsky's students Mosolov and Shebalin -- arrived too late. Derzhanvosky's wife was with the corpse of her husband for four days. They buried him quickly, digging the grave by themselves.

Myaskovsky's Symphony 24 was dedicated to the memory of Derzhanovsky. What strikes me the most about this work is its economy. All three movement are made up of two to three long-breathed themes, being passed from one instrumental group to another and engaging in fugal treatments. Yet the ebb and flow of dynamics is so natural it is almost like breathing.

The symphony started with a brass fanfare, which was rather incongruent. In 1939, a young conductor of military wind band called Ivan Petrov befriended Myaskovsky, and given Myaskovsky's military background, Petrov's zeal in reforming the musical groups in the military impressed him, and that reignited Myaskovsky's interest in brass music. Petrov would become a solace to the old composer in his last dark years. The brass theme is soon passed to the strings, and subsequently being weaved into counterpoint.

The second movement is even more effective. Again the ingredients are similar: lyrical themes being weaved into counterpoint -- you can criticize the symphony on the ground that the counterpoints are too insistent, but recall Prokofiev's admonition to Myaskovsky about his First Symphony: "you are writing this counterpoint to please conservatoire teachers, when you should have let the theme shine on its own lyrical beauty!" But as a mature composer, Myaskovsky could have his cake and eat it too: the themes are given space to shine, and the counterpoint would please any academic. What is impressive about this movement is how the dynamics is organized: the music progresses like cascading, mounting waves. Patrick Zuk suggests that the symphony may recall the sound-world of Vaughan Williams, and I think this is especially true for the second movement. The final movement is again very brassy, but with a dark undertone of deep woodwinds. A triumphant mood gradually establishes, and transformed into a radiant serenity that ends the work.

The mood of the whole symphony is somewhat ambivalent: is it a farewell to a enterprising friend and benefactor? Myaskovsky is too complex to be subjected to simplistic narratives, a trap that people falls in when they hear the opening brass fanfare and deem the music as "social realist response to the war". The only thing we can do is to take the music on its own terms.

Derzhanovsky and Melkikh were hardly the only close person Myaskovsky lost during the war. His niece died giving birth to a stillborn child.