- Joined

- Jul 18, 2020

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

CUTE ANIMALS, ASSEMBLE!

- Thread starter Bugaboo

- Start date

- Joined

- Feb 19, 2023

- Joined

- Feb 2, 2023

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2024

Ponies from Exmoor, a park between Somerset and North Devon, that migrated to Cromwell Bottom Nature Reserve, near Brighouse, West Yorkshire.

@Anonitolia The orangutan, and the capyblappy and anteater crack me up.

- Joined

- Mar 16, 2025

- Joined

- Jan 2, 2023

- Joined

- Jul 18, 2020

Ventrue

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Oct 31, 2023

- Joined

- Jul 18, 2020

@AnOminous

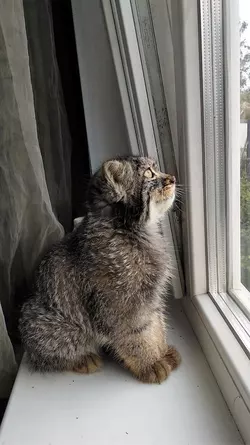

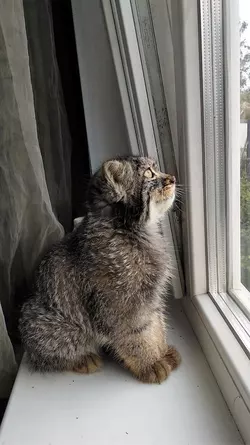

The Story of a Wild Kitten from Vadim Kirilyuk, Director of the Daursky Nature Reserve

More manul-human interactions.

The Story of a Wild Kitten from Vadim Kirilyuk, Director of the Daursky Nature Reserve

She wasn’t even a month old when the iron wagon, where the manul cats had their den, was moved. Dasha was the only survivor of the litter. She was taken in by a human family—the family of Vadim and Olga Kirilyuk.

Dasha stopped fearing her new “parents” after just a couple of feedings. They set up a “den” for her in a cardboard box with a fur hat inside. After feeding, they always massaged her tummy to aid digestion: “That’s how Mom did it. Then back to the ‘den,’ covering her with a hand for a moment. Little Dasha fell asleep quickly.”

Gradually, they switched her to a bottle… a human one, as she refused a special cat one. Over time, she transitioned to milk and kitten formula, and at one and a half months, they gave her meat. “No minced meat—a predator needs to chew.”

When they first took Dasha outside, she got scared, ran back to her people, and complained. The reserve director notes that at this age, female manuls typically lead their offspring away from their first den. “We had to teach Dasha to live in the wild. A human can’t replicate the skills of her real mother, but without training, she’d have no chance of learning to survive on her own.” After walks, the kitten would joyfully greet the house.

Like all felines, Dasha loved sharpening her claws. “Even as a tiny manul, her claws were large and sharp. At a month old, they still didn’t retract. She’d walk across the floor, and her claws would clack. Climbing onto your legs, she’d leave deep scratches (for ‘Mom,’ that meant goodbye to summer skirts). Pushing away or pulling in the bottle with her paws would also leave scratches,” Kirilyuk writes.

There were issues with the litter box at first, too. She’d mark rags, make a toilet behind the wardrobe, and mess up the house cats’ feeder. By two months, she figured out to use a sandbox. Later, after watching the other cats, she began burying her waste. Clever girl!

Yet she was a wild cat, and as she matured, she increasingly lived on her own terms. She began sleeping apart from her “parents.” “You wake up in the morning, and Dasha’s already quietly sitting by the window, watching the village street. At night and early morning, she was very considerate, trying not to wake anyone. Though generally quite vocal, she’d ask for food modestly—sucking on a palm pad for milk or scampering to the fridge when it opened, scratching at it on her hind legs, begging for chicken.” The house pets did the same; it must be in their blood.

“From the start, it was clear she couldn’t stay with us long. As she grew, she became more independent. Dasha preferred staying outside, growing wilder and resenting any limits on her freedom,” the reserve director observes. He explains that at four to five months, young manuls leave their mothers to live independently. Between 50-90% of them perish in their first 10 months, depending on winter conditions.

The manul gradually started adapting to life outside: the yard, rocky terrain. Vadim Evgenyevich notes that at three months, young manuls roam with their mother’s family, changing shelters and learning life skills—how to hide, stalk silently, leap instantly, and kill. Without these, survival is impossible. Dasha honed her skills too—playing actively with the adults, chasing the cat Timka, stalking and pouncing on a rabbit. Sometimes she’d sleep next to her feline kin, but at night, she’d return to her “parents,” pushing the other cats aside.

On her fifth day at the outpost, Dasha caught a pika calf while hunting with “Mom” in the morning. Classic waiting by the burrow paid off. She began realizing that frantic leaps and chases led nowhere. That same day, she took down a near-adult pika. “True, she had help—the pika darted out of a slightly open trap. For her first lessons, she’d earn a solid B.”

In six days, Dasha mastered the outpost—where to hide, how food smelled, and gained her first hunting experience.

By mid-September, Dasha had reached two kilograms, a normal weight. She still had a month and a half to grow and store fat. “Dasha, with such rich natural food, we’ll make it work. In March, you’ll meet your first tomcat, then give birth to your first blue-eyed manul kittens,” Vadim Evgenyevich says to his charge.

…More and more, Dasha gazed at the nearby rocks. During one of her “parent’s” trips away, she left, leaving behind an uneaten pika. The little manul chose complete freedom.

Translated from here.

“That’s How Mom Did It”

The little manul was named Dasha Budlanovna, her patronymic derived from the name of the mountain near which she was born. They began feeding her saline solution through a syringe to combat dehydration, later adding milk to her diet. “For the first 24 hours, we gave Dasha fluids every 2-3 hours. Would she survive or not? Would the new food suit her, would her tiny body adapt quickly enough? The chance of losing such a small, weakened kitten in the first days and weeks is very high,” Vadim Evgenyevich wrote on his social media page.

Dasha stopped fearing her new “parents” after just a couple of feedings. They set up a “den” for her in a cardboard box with a fur hat inside. After feeding, they always massaged her tummy to aid digestion: “That’s how Mom did it. Then back to the ‘den,’ covering her with a hand for a moment. Little Dasha fell asleep quickly.”

Gradually, they switched her to a bottle… a human one, as she refused a special cat one. Over time, she transitioned to milk and kitten formula, and at one and a half months, they gave her meat. “No minced meat—a predator needs to chew.”

Claws and Toilet

Dasha quickly adapted to her new home. “Climbing over her ‘den’ and then onto a hanging blanket, Dasha soon learned to scramble onto the couch. In the evening, she’d settle into her ‘den’ on her own. During the day, it was moved to the living room, and at night, to the bedroom, closer to her ‘parents,’” Vadim recounts, tracking every small step of the manul’s progress.

When they first took Dasha outside, she got scared, ran back to her people, and complained. The reserve director notes that at this age, female manuls typically lead their offspring away from their first den. “We had to teach Dasha to live in the wild. A human can’t replicate the skills of her real mother, but without training, she’d have no chance of learning to survive on her own.” After walks, the kitten would joyfully greet the house.

Like all felines, Dasha loved sharpening her claws. “Even as a tiny manul, her claws were large and sharp. At a month old, they still didn’t retract. She’d walk across the floor, and her claws would clack. Climbing onto your legs, she’d leave deep scratches (for ‘Mom,’ that meant goodbye to summer skirts). Pushing away or pulling in the bottle with her paws would also leave scratches,” Kirilyuk writes.

There were issues with the litter box at first, too. She’d mark rags, make a toilet behind the wardrobe, and mess up the house cats’ feeder. By two months, she figured out to use a sandbox. Later, after watching the other cats, she began burying her waste. Clever girl!

Whiskered Relatives

And what about the house cats (there were three—editor’s note)? How did they react to this seemingly familiar yet alien kitten? “Two of them are pampered city ladies, and one is a battle-weary, scarred village tomcat. Dasha’s relationships with them didn’t form right away.” The house cats didn’t like the wild kitten’s smell. They’d hiss and swat at her. But brave Dasha soon feared none of them: she’d puff up and advance. The tomcat Murzik steered clear of this ball of fury. Sickly, weak Musya was the first to accept Dasha. “They never groomed each other, but they learned to lie peacefully together on the ‘parents’ bed or side by side in an armchair,” Kirilyuk writes.

Proud

Dasha grew up headstrong: she loved scratches and “fights” with hands or feet, accompanied by loud, distinctive yips. When she didn’t want to play, she’d protest. If she wasn’t in the mood, it was best not to touch her. She accepted affection with joy or resignation only from “Mom”—Olga Kuzminichna. Dasha always displayed her pride and independence.

Yet she was a wild cat, and as she matured, she increasingly lived on her own terms. She began sleeping apart from her “parents.” “You wake up in the morning, and Dasha’s already quietly sitting by the window, watching the village street. At night and early morning, she was very considerate, trying not to wake anyone. Though generally quite vocal, she’d ask for food modestly—sucking on a palm pad for milk or scampering to the fridge when it opened, scratching at it on her hind legs, begging for chicken.” The house pets did the same; it must be in their blood.

Thirst for Freedom

By her fourth month, Dasha increasingly wanted to spend time outdoors. Left alone at home, she’d start complaining: “ee-yav-vav-vav.” The yard beckoned her, and she even made a den in a woodpile.

“From the start, it was clear she couldn’t stay with us long. As she grew, she became more independent. Dasha preferred staying outside, growing wilder and resenting any limits on her freedom,” the reserve director observes. He explains that at four to five months, young manuls leave their mothers to live independently. Between 50-90% of them perish in their first 10 months, depending on winter conditions.

A New Home

What could be the fate of a manul raised by humans? Keeping her at home wasn’t an option, nor was a zoo. The “parents” were determined from the start to return her to the wild. To make her a true wild cat, they brought Dasha to a new home—the Adon-Chelon section of the Daursky Nature Reserve, an area with prime manul habitats. Dasha bolted immediately, but they brought her back to familiarize her with her new den, the place with “family” and food. Vadim Evgenyevich says she caught and killed mice but didn’t like eating them. The biggest danger at the outpost was that she might leave and not return. “We held onto hope that she wasn’t fully independent yet and still needed her family.” From morning to night, Dasha explored the outpost. Thus began her life in her new place.

The manul gradually started adapting to life outside: the yard, rocky terrain. Vadim Evgenyevich notes that at three months, young manuls roam with their mother’s family, changing shelters and learning life skills—how to hide, stalk silently, leap instantly, and kill. Without these, survival is impossible. Dasha honed her skills too—playing actively with the adults, chasing the cat Timka, stalking and pouncing on a rabbit. Sometimes she’d sleep next to her feline kin, but at night, she’d return to her “parents,” pushing the other cats aside.

A Wild Beast, After All

Dasha’s wild nature showed early on. She disliked strangers and growled menacingly at an unfamiliar visitor. When her “parent” tried to calm her, he got the brunt of it. “The next day, in a similar situation, Mom got it too. That was the end of kinship. A manul is a solitary wild predator from birth, and family is a temporary thing…” her “parent” concluded.

On her fifth day at the outpost, Dasha caught a pika calf while hunting with “Mom” in the morning. Classic waiting by the burrow paid off. She began realizing that frantic leaps and chases led nowhere. That same day, she took down a near-adult pika. “True, she had help—the pika darted out of a slightly open trap. For her first lessons, she’d earn a solid B.”

In six days, Dasha mastered the outpost—where to hide, how food smelled, and gained her first hunting experience.

“The Ugly Duckling”

A mature sternness appeared in Dasha’s gaze. Then they brought the cat Timka to the outpost, and she began claiming the territory. “Feeling like the boss here, Dasha chased her around the house and yard. Sometimes she’d follow and diligently bury Timka’s toilet spots. Lagging in speed and especially in jumping onto high objects, Dasha made up for it with persistence, never backing down. She used a non-aggressive but insistent displacement tactic.” Timka fended off the pesky manul with growls and swats. Dasha never won the love or affection of her whiskered kin. “To the house cats, she was an ‘ugly kitten.’”

Attachment to Family

Dasha was hesitant to venture beyond the outpost fence, just as she was reluctant to stray far from her “parents.” “Mutual attachment and love keep her with us. This half-grown female manul hasn’t lost her interest in play and fun—quite the opposite. It seemed the further along she got, the more Dasha showed her attachment. As if she feared parting with childhood, her family, and turning into a stern, solitary predator. But time is relentless. Most of her wild peers have long been living on their own,” Vadim nearly concludes.

By mid-September, Dasha had reached two kilograms, a normal weight. She still had a month and a half to grow and store fat. “Dasha, with such rich natural food, we’ll make it work. In March, you’ll meet your first tomcat, then give birth to your first blue-eyed manul kittens,” Vadim Evgenyevich says to his charge.

…More and more, Dasha gazed at the nearby rocks. During one of her “parent’s” trips away, she left, leaving behind an uneaten pika. The little manul chose complete freedom.

Translated from here.

More manul-human interactions.

- Joined

- Jul 6, 2022

Male spider tries courting the female spider and after being ignored looks for the moral

support from its owner

support from its owner

- Joined

- Feb 6, 2025

- Joined

- Apr 12, 2020

- Joined

- Mar 18, 2019

- Joined

- Dec 21, 2020

- Joined

- Mar 1, 2020

- Joined

- Mar 18, 2019

- Joined

- Aug 24, 2014

- Joined

- Apr 12, 2020

- Joined

- Jul 27, 2022

- Joined

- Apr 9, 2022