article/archive

Inside a home on a quiet street in southern New Hampshire, a mom scrubs at dirty fingerprints, food stains and some dog hair on a wall she’s preparing to paint.

It’s one of many projects underway, so the family can sell the home next month if New Hampshire lawmakers approve anti-transgender bills advancing through each chamber.

No one in the family wants to move. Rosie and her husband, Ian, grew up in New Hampshire. Their parents and immediate family live here. The house is on a quiet street with other children for their three kids to play with. There’s a good size yard for chickens, trees just right for climbing and a small creek.

“We’d prefer if New Hampshire stayed a safe place for our family,” said Rosie. “I go between being bummed and depressed about it, and being really pissed off that people don’t seem to understand — these things have real life consequences.”

One of the bills could make it a felony to provide Rosie and Ian’s middle child, Emily, the medication they take to delay the start of male puberty. WBUR agreed not to publish the family's last name because of the legal risks they could face if this legislation takes effect.

Another bill would let businesses, schools and government agencies require that 8-year-old Emily, who has long blue, or sometimes green, hair and a love of purple clothing with rainbows, use a men’s bathroom. The bills passed the New Hampshire House and are pending in the Senate.

“I don’t think it’s worth living here under that threat,” said Rosie, “so our hands are tied.”

More than two dozen states have already enacted laws that ban or limit prescriptions for drugs that pause puberty and the hormone therapy given to teenagers who want to transition from male to female or female to male. A Trump administration report released early this month is the latest effort to press for that ban nationwide. It says psychotherapy not medications should be the main treatment for anyone under age 19 who identifies as transgender or nonbinary.

The report followed an executive order that said the U.S. would stop funding “these destructive and life-altering procedures.” A judge has temporarily blocked that order, but in the meantime, some clinics have already stopped offering what’s known as gender-affirming care for youth.

Emily's family, and many like them, are disturbed to find themselves at the center of fierce cultural and political debates.

“It’s just so weird to make really personal decisions in this political climate,” Rosie said. “We’re constantly having to prove to the world that being transgender is real, that it’s not something I’m making up, that my kid has a right to exist.”

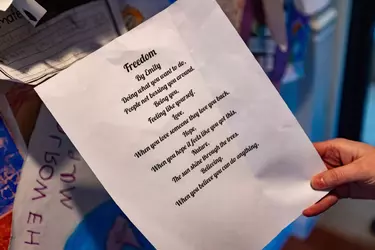

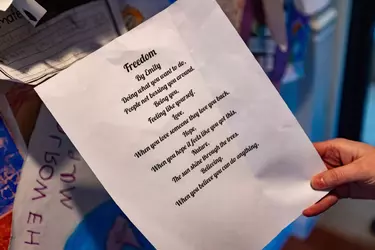

Emily loves to read, rollerblade, ride a bike, practice the piano and play video games. Some days the passion might be drawing, tumbling, shooting nerf guns, or cuddling with the family guinea pigs or dogs. Emily says they don’t feel like a boy or a girl. "They" is Emily’s preferred pronoun.

“Because it means I can be myself,” Emily said. “I can do what I need to do to let me be me.”

Sometimes Emily’s friends mess up, but they don’t mind.

“I let my friends call me boy or girl because, like, I know they know who I am,” Emily said.

Emily was born with a rare brain disorder called apraxia of speech that made it hard to express thoughts out loud. A speech therapist helped Emily learn to send the right signals to their muscles, lips and tongue. Most people couldn’t understand what they were saying until Emily was about 4 ½. Among Emily’s first requests: a dress.

Rosie, a mental health counselor, and Ian, who works in construction, added dresses to Emily’s wardrobe and books about kids who weren’t specifically a girl or a boy to the family library.

Emily remembers asking at bedtime one night to hear more about being trans. Emily was 5 at the time.

“A few days later, I said, ‘Mom, can I be trans?’ ” recounted Emily in a recent interview with Rosie and Ian on the family couch. As they remembered those early days, Emily lay draped over first one parent's lap, then the other's.

Rosie has worked with transgender adults. But she had no idea what being transgender would mean for her child.

“They were telling us that there’s more,” Rosie said, pausing to consider what there was more to.

“To me?” Emily offered.

“Yeah, that there’s more to you. I like that,” said Rosie. “We felt a little out of our league though. I didn’t know what we should be doing and what we shouldn’t be doing.”

“But you supported me,” Emily interrupted.

“We always try and support you,” Rosie said, patting Emily’s leg.

Supporting Emily, and making sure they are safe and feel loved, have become touchstones for Rosie and Ian even as doing so has become more confusing, frustrating and scary.

Emily's question — “Can I be trans?” — came as a growing number of Republican-controlled state legislatures were finding ways to answer, "No." It came as gender clinics for children were becoming targets for threats, and as President Trump was pledging to dismantle the “woke agenda,” including transgender rights.

Ian was hesitant himself, at first, about calling his child transgender.

“I felt it was kind of young,” Ian said. “But through research and just being around it, I figured out that you just feel the way you feel, like how I felt straight. You just feel it at an early age.”

Ian is angry at politicians for “energizing people to hate people they’ve never met and don’t understand.” He tries not to ruminate on ways that hate could be turned against his child.

“I feel pretty fearful of the harm and emotional damage to them if they meet the wrong person on a bad day,” Ian said. “But if Emily is happy and safe and feels welcome, then dealing with the politics will all be worth it.”

At age 6, Emily started seeing a therapist in New Hampshire who had some experience with transgender children, and going to a gender clinic for children in Boston. The next year, Emily and Rosie spent a week at a summer camp for trans kids and their families. The family joined a group of families with nonbinary kids to trade information and arrange playdates.

Rosie watched Emily grow into a child more confident, playful and at peace with themselves. But she knew puberty wasn’t far off. Emily's older brother began showing signs at 9. Emily was clear, they did not want to be hairy like Ian or have a deep voice.

If Emily started developing as male, Rosie worried that “they would be constantly at war with their body.”

A doctor at the gender clinic said the first step to avoid that war for Emily would be to put puberty on hold. Rosie expected to map out a plan for doing that before Emily turned 9 this June. Then Trump won the election and their plans changed.

Emily, Rosie and Pearl, one of the family guinea pigs, headed to the clinic in Boston the Friday before Trump began his second term.

“I think we got the last appointment before the inauguration,” Rosie said.

Trump signed his order to enact a ban on gender-affirming care for children eight days after he was sworn in. The ban hasn't taken effect amid a court challenge.

Given the political climate, the family said they made the right decision starting Emily on puberty blockers some months earlier than expected. But it's not what they wished. Rosie and Ian wanted to choose the best time with their doctor.

“The biggest bummer was being forced to do it then, instead of waiting,” Ian said.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health recommends pausing puberty after it has started for children who feel intense discomfort with their changing body. Rosie said the benefit of starting Emily while they were still sure they could outweighed any risk because Emily has consistently said they want to look like Rosie, not Ian, when they grow up.

“My kid is very indecisive around everything else in their life,” said Rosie. “So for them to have this be so consistent is — that's all I need to know.”

On the inside of Emily’s upper left arm, a 1-inch implant slowly releases the puberty suppression medication. The effects are reversible in that puberty will resume when the implant is removed or the medicine runs out. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) says delaying puberty gives children time to explore their identity, get counseling, develop coping skills and learn about future treatment options.

Some research shows that transgender children who received puberty blockers are less anxious and depressed than trans kids who don’t. Other reviews find little impact. The blocker may pose risks for developing bones and fertility.

Many doctors who treat transgender children say bone density catches up when patients resume puberty, as does sperm or egg development if the child continues puberty in their sex determined at birth. If they transition to the opposite sex, they may have fertility problems later in life. That decision is four or five years away for Emily.

“I think about those risks a little bit, but it feels pretty far off,” said Ian. He shrugs and adds the family is, “just trying to get through” the challenges right in front of them.

For the first step of suppressing puberty, published research on the long term effects for bone health and fertility is “limited” and “varied,” according to the AAP. The group still supports the use of puberty blockers to treat children with gender dysphoria as does the nation’s largest group of physicians, the American Medical Association. But the United Kingdom and some other countries have concluded the risks outweigh the benefits and have largely banned their use. The Trump administration points to those decisions as evidence the U.S. should do the same.

Some parents of transgender kids struggle to make sense of competing research and reports in this fraught environment.

“It’s a new science, which scares me a bit,” Ian said. “But the puberty blockers are reversible if Emily changes their mind. So I have comfort in that.”

If Emily does not change their mind, the implant will need to be replaced every year or two until Emily is ready to begin puberty as a girl or as a boy.

Rosie and Ian hear all kinds of pronouncements about how to raise a transgender child, ranging from “just follow their lead,” to “children aren’t mature enough to make such life-altering decisions.”

“There's a lot of things I don’t follow my kid's lead on, like if I let them follow their lead on cleaning their rooms, we wouldn’t get very far,” Rosie said with a laugh. “But I’ve learned that there’s a lot of things that our kids actually do really know that I can’t know. And so, I have to trust them.”

Rosie needs to finish painting the stairwell a misty, hide-the-dirt, gray. Ian is replastering walls in the basement. Rosie has a spreadsheet of seven cities and towns in northern Massachusetts where the schools seem good, the communities seem welcoming for a trans kid and where they think they could afford a home. Rosie is collecting guidance through webinars and from other parents of transgender children about how to have the “we’re moving” conversations with her three kids.

The kids have lots of questions. Will the new yard have a treehouse? Will we have to share a room? What school will we go to?

Emily has come crying about a move, worried their brother and sister will be mad and blame Emily. Rosie told Emily the blame will be on state lawmakers in Concord who are afraid of things they don’t understand.

Ian and Rosie have assured the kids they’ll have a family meeting before making any final decisions. The New Hampshire Legislature wraps up business for the year by the end of June.

Even if they move states, there’s no guarantee transgender care will continue to be available for Emily. State health leaders in Massachusetts have pledged to maintain access for kids. But the president’s deputy chief of staff, Stephen Miller, described gender medications and surgery for minors as “barbaric” and “child abuse” earlier this month, confirming the White House's commitment to curtail if not end it.

Plan B is Thailand. Rosie can work remotely. Ian has trade skills that might be useful there. And it’s a longtime haven for transgender people seeking care.

“I have to plan for the worst so that I can stay and continue to fight,” Rosie said, with a nervous laugh. And Rosie feels sure of what she’s fighting for.

“I want to make sure that Emily knows they are loved, no matter what,” Rosie said, standing in her driveway one afternoon, watching the kids ride bikes. “It’s not their name, it’s not the clothes they wear, it’s not the way they cut their hair, it’s who they are, in their heart.”

This segment aired on May 20, 2025.

Photos:

Inside a home on a quiet street in southern New Hampshire, a mom scrubs at dirty fingerprints, food stains and some dog hair on a wall she’s preparing to paint.

It’s one of many projects underway, so the family can sell the home next month if New Hampshire lawmakers approve anti-transgender bills advancing through each chamber.

No one in the family wants to move. Rosie and her husband, Ian, grew up in New Hampshire. Their parents and immediate family live here. The house is on a quiet street with other children for their three kids to play with. There’s a good size yard for chickens, trees just right for climbing and a small creek.

“We’d prefer if New Hampshire stayed a safe place for our family,” said Rosie. “I go between being bummed and depressed about it, and being really pissed off that people don’t seem to understand — these things have real life consequences.”

One of the bills could make it a felony to provide Rosie and Ian’s middle child, Emily, the medication they take to delay the start of male puberty. WBUR agreed not to publish the family's last name because of the legal risks they could face if this legislation takes effect.

Another bill would let businesses, schools and government agencies require that 8-year-old Emily, who has long blue, or sometimes green, hair and a love of purple clothing with rainbows, use a men’s bathroom. The bills passed the New Hampshire House and are pending in the Senate.

“I don’t think it’s worth living here under that threat,” said Rosie, “so our hands are tied.”

More than two dozen states have already enacted laws that ban or limit prescriptions for drugs that pause puberty and the hormone therapy given to teenagers who want to transition from male to female or female to male. A Trump administration report released early this month is the latest effort to press for that ban nationwide. It says psychotherapy not medications should be the main treatment for anyone under age 19 who identifies as transgender or nonbinary.

The report followed an executive order that said the U.S. would stop funding “these destructive and life-altering procedures.” A judge has temporarily blocked that order, but in the meantime, some clinics have already stopped offering what’s known as gender-affirming care for youth.

Emily's family, and many like them, are disturbed to find themselves at the center of fierce cultural and political debates.

“It’s just so weird to make really personal decisions in this political climate,” Rosie said. “We’re constantly having to prove to the world that being transgender is real, that it’s not something I’m making up, that my kid has a right to exist.”

About Emily

Emily loves to read, rollerblade, ride a bike, practice the piano and play video games. Some days the passion might be drawing, tumbling, shooting nerf guns, or cuddling with the family guinea pigs or dogs. Emily says they don’t feel like a boy or a girl. "They" is Emily’s preferred pronoun.

“Because it means I can be myself,” Emily said. “I can do what I need to do to let me be me.”

Sometimes Emily’s friends mess up, but they don’t mind.

“I let my friends call me boy or girl because, like, I know they know who I am,” Emily said.

Emily was born with a rare brain disorder called apraxia of speech that made it hard to express thoughts out loud. A speech therapist helped Emily learn to send the right signals to their muscles, lips and tongue. Most people couldn’t understand what they were saying until Emily was about 4 ½. Among Emily’s first requests: a dress.

Rosie, a mental health counselor, and Ian, who works in construction, added dresses to Emily’s wardrobe and books about kids who weren’t specifically a girl or a boy to the family library.

Emily remembers asking at bedtime one night to hear more about being trans. Emily was 5 at the time.

“A few days later, I said, ‘Mom, can I be trans?’ ” recounted Emily in a recent interview with Rosie and Ian on the family couch. As they remembered those early days, Emily lay draped over first one parent's lap, then the other's.

Rosie has worked with transgender adults. But she had no idea what being transgender would mean for her child.

“They were telling us that there’s more,” Rosie said, pausing to consider what there was more to.

“To me?” Emily offered.

“Yeah, that there’s more to you. I like that,” said Rosie. “We felt a little out of our league though. I didn’t know what we should be doing and what we shouldn’t be doing.”

“But you supported me,” Emily interrupted.

“We always try and support you,” Rosie said, patting Emily’s leg.

Supporting Emily, and making sure they are safe and feel loved, have become touchstones for Rosie and Ian even as doing so has become more confusing, frustrating and scary.

Emily's question — “Can I be trans?” — came as a growing number of Republican-controlled state legislatures were finding ways to answer, "No." It came as gender clinics for children were becoming targets for threats, and as President Trump was pledging to dismantle the “woke agenda,” including transgender rights.

Ian was hesitant himself, at first, about calling his child transgender.

“I felt it was kind of young,” Ian said. “But through research and just being around it, I figured out that you just feel the way you feel, like how I felt straight. You just feel it at an early age.”

Ian is angry at politicians for “energizing people to hate people they’ve never met and don’t understand.” He tries not to ruminate on ways that hate could be turned against his child.

“I feel pretty fearful of the harm and emotional damage to them if they meet the wrong person on a bad day,” Ian said. “But if Emily is happy and safe and feels welcome, then dealing with the politics will all be worth it.”

At age 6, Emily started seeing a therapist in New Hampshire who had some experience with transgender children, and going to a gender clinic for children in Boston. The next year, Emily and Rosie spent a week at a summer camp for trans kids and their families. The family joined a group of families with nonbinary kids to trade information and arrange playdates.

Rosie watched Emily grow into a child more confident, playful and at peace with themselves. But she knew puberty wasn’t far off. Emily's older brother began showing signs at 9. Emily was clear, they did not want to be hairy like Ian or have a deep voice.

If Emily started developing as male, Rosie worried that “they would be constantly at war with their body.”

A doctor at the gender clinic said the first step to avoid that war for Emily would be to put puberty on hold. Rosie expected to map out a plan for doing that before Emily turned 9 this June. Then Trump won the election and their plans changed.

Starting puberty blockers

Emily, Rosie and Pearl, one of the family guinea pigs, headed to the clinic in Boston the Friday before Trump began his second term.

“I think we got the last appointment before the inauguration,” Rosie said.

Trump signed his order to enact a ban on gender-affirming care for children eight days after he was sworn in. The ban hasn't taken effect amid a court challenge.

Given the political climate, the family said they made the right decision starting Emily on puberty blockers some months earlier than expected. But it's not what they wished. Rosie and Ian wanted to choose the best time with their doctor.

“The biggest bummer was being forced to do it then, instead of waiting,” Ian said.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health recommends pausing puberty after it has started for children who feel intense discomfort with their changing body. Rosie said the benefit of starting Emily while they were still sure they could outweighed any risk because Emily has consistently said they want to look like Rosie, not Ian, when they grow up.

“My kid is very indecisive around everything else in their life,” said Rosie. “So for them to have this be so consistent is — that's all I need to know.”

On the inside of Emily’s upper left arm, a 1-inch implant slowly releases the puberty suppression medication. The effects are reversible in that puberty will resume when the implant is removed or the medicine runs out. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) says delaying puberty gives children time to explore their identity, get counseling, develop coping skills and learn about future treatment options.

Some research shows that transgender children who received puberty blockers are less anxious and depressed than trans kids who don’t. Other reviews find little impact. The blocker may pose risks for developing bones and fertility.

Many doctors who treat transgender children say bone density catches up when patients resume puberty, as does sperm or egg development if the child continues puberty in their sex determined at birth. If they transition to the opposite sex, they may have fertility problems later in life. That decision is four or five years away for Emily.

“I think about those risks a little bit, but it feels pretty far off,” said Ian. He shrugs and adds the family is, “just trying to get through” the challenges right in front of them.

For the first step of suppressing puberty, published research on the long term effects for bone health and fertility is “limited” and “varied,” according to the AAP. The group still supports the use of puberty blockers to treat children with gender dysphoria as does the nation’s largest group of physicians, the American Medical Association. But the United Kingdom and some other countries have concluded the risks outweigh the benefits and have largely banned their use. The Trump administration points to those decisions as evidence the U.S. should do the same.

Some parents of transgender kids struggle to make sense of competing research and reports in this fraught environment.

“It’s a new science, which scares me a bit,” Ian said. “But the puberty blockers are reversible if Emily changes their mind. So I have comfort in that.”

If Emily does not change their mind, the implant will need to be replaced every year or two until Emily is ready to begin puberty as a girl or as a boy.

Rosie and Ian hear all kinds of pronouncements about how to raise a transgender child, ranging from “just follow their lead,” to “children aren’t mature enough to make such life-altering decisions.”

“There's a lot of things I don’t follow my kid's lead on, like if I let them follow their lead on cleaning their rooms, we wouldn’t get very far,” Rosie said with a laugh. “But I’ve learned that there’s a lot of things that our kids actually do really know that I can’t know. And so, I have to trust them.”

In a holding pattern

Rosie needs to finish painting the stairwell a misty, hide-the-dirt, gray. Ian is replastering walls in the basement. Rosie has a spreadsheet of seven cities and towns in northern Massachusetts where the schools seem good, the communities seem welcoming for a trans kid and where they think they could afford a home. Rosie is collecting guidance through webinars and from other parents of transgender children about how to have the “we’re moving” conversations with her three kids.

The kids have lots of questions. Will the new yard have a treehouse? Will we have to share a room? What school will we go to?

Emily has come crying about a move, worried their brother and sister will be mad and blame Emily. Rosie told Emily the blame will be on state lawmakers in Concord who are afraid of things they don’t understand.

Ian and Rosie have assured the kids they’ll have a family meeting before making any final decisions. The New Hampshire Legislature wraps up business for the year by the end of June.

Even if they move states, there’s no guarantee transgender care will continue to be available for Emily. State health leaders in Massachusetts have pledged to maintain access for kids. But the president’s deputy chief of staff, Stephen Miller, described gender medications and surgery for minors as “barbaric” and “child abuse” earlier this month, confirming the White House's commitment to curtail if not end it.

Plan B is Thailand. Rosie can work remotely. Ian has trade skills that might be useful there. And it’s a longtime haven for transgender people seeking care.

“I have to plan for the worst so that I can stay and continue to fight,” Rosie said, with a nervous laugh. And Rosie feels sure of what she’s fighting for.

“I want to make sure that Emily knows they are loved, no matter what,” Rosie said, standing in her driveway one afternoon, watching the kids ride bikes. “It’s not their name, it’s not the clothes they wear, it’s not the way they cut their hair, it’s who they are, in their heart.”

This segment aired on May 20, 2025.

Photos: