Three years after the fall of Roe v. Wade, abortion bans have driven residents from some states, one study finds

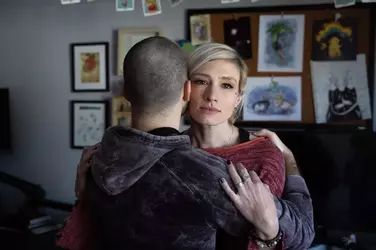

Alana Tedmon and her husband moved to Philadelphia last summer from Texas. Photo: Rachel Wisniewski for WSJ

By Laura Kusisto and Harriet Torry

July 6, 2025 7:00 am ET

Alana Tedmon and her husband moved to the outskirts of Dallas in June 2022, attracted by the lower cost of living and proximity to family. That same month, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and Texas followed by banning abortion through all nine months of pregnancy.

“It seemed like people were always trying to change the legislation around abortion every single year but I never thought it would really happen legitimately,” she said.

The 37-year-old freelance illustrator and her husband moved back to Philadelphia last summer, largely because of the ban. Then Tedmon got pregnant unexpectedly. She was initially excited, but anxiety about the couple’s financial security ultimately led her to get an abortion—something she was grateful was feasible in the state.

“If we have a child, I want it to be because we’re ready, and not because ‘oops, it just happened,’” she said.

Abortion is now banned or heavily restricted in about one-third of U.S. states, and some women of childbearing age say that has introduced a new calculus about where to live and work. Though migration patterns are complicated, early data show that the states with the most restrictive laws are seeing some residents leave.

A recent paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research estimated that 13 states with abortion bans collectively saw about 146,000 residents leave due to abortion bans in the year after the Supreme Court eliminated the constitutional right to the procedure. The paper found that while those states—mostly in the South—had been gaining population at a significantly faster rate than other parts of the country, that advantage essentially vanished afterward. The authors looked at patterns in Postal Service change-of-address data after the Supreme Court’s ruling.

Over a five-year period, those states’ populations could be about 1% smaller than if they hadn’t passed abortion restrictions, the paper estimated.

Texas' abortion ban was largely behind the decision of Alana Tedmon, a freelance illustrator, to leave the state. Rachel Wisniewski for WSJ

The extent to which women are making decisions about where to live based on abortion bans has been more pronounced than many economists who study this issue anticipated.

“A single policy change is unlikely to be the marginal factor in deciding on a move. And yet here we have this really strong new evidence that abortion policy really is impacting migration,” said Caitlin Myers, an economist at Middlebury College who studies abortion data. The overturning of Roe, Myers said, was “a moment of understanding the extent to which state policies can become very, very salient.”

Another recent study found a decline in the proportion of high-achieving women applying to universities in states with abortion bans after Roe was overturned compared with a couple of years earlier. Research has also shown a decline in applications to medical school residencies in states that have heavily restricted abortion.

Research in this field remains in a relatively early phase, and the impacts identified so far are small in the context of the larger U.S. economy. For the most part, big companies haven’t made large public shifts in hiring as a result of state-level abortion rules.

The out-migration trend has been most sustained for single people, reflecting the fact that younger people are more likely to be more mobile and better able to move on principle, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research paper. That means that states with bans stand to lose out on workers in some of their prime career-building years.

In interviews, some women who are factoring abortion laws into their life decisions cited worries about suffering complications during a planned pregnancy and being unable to get care or having to travel out of state for an emergency abortion, which can cost in the tens of thousands of dollars.

Kayla Smith had lived in Idaho for more than a decade. But she decided to move after the state’s ban prevented her from obtaining an abortion in her home state for her unborn son who was suffering from a fatal fetal heart condition.

She and her husband took out a $16,000 personal loan because they weren’t sure if their health-insurance provider would cover her abortion in Washington state. That was in addition to travel expenses. (Nine months later her insurance company reimbursed her for the procedure.)

When Smith got pregnant again, the couple left Idaho for good, even though that meant moving to a corner of Washington with limited obstetric care. “That to us was safer than staying in the state of Idaho,” Smith said.

Kayla Smith, in light blue coat, moved from Idaho after the state’s ban prevented her from obtaining an abortion for her unborn son, who had a fatal fetal heart condition. Photo: Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters

Some women say abortion bans have curtailed their earnings and career advancement, forcing them to forgo conferences or other work travel while pregnant, concerned they wouldn’t be able to obtain emergency medical care. All bans allow doctors to terminate a pregnancy to save the life of the mother, but those exceptions don’t encompass all emergency situations and in practice doctors also have sometimes found them difficult to apply.

For Emilie Aries, who regularly traveled about 40 times a year as a consultant and keynote speaker, the fear of being unable to get emergency care was so great that she decided during her second pregnancy to stop traveling to states with bans. She had suffered a series of miscarriages before that. She said she lost tens of thousands of dollars in income because she wouldn’t travel to states such as Texas.

“No amount of money is worth putting my life at risk. It’s a terrible position to be put in, quite frankly,” Aries said.

Source (Archive)