December 5, 2024

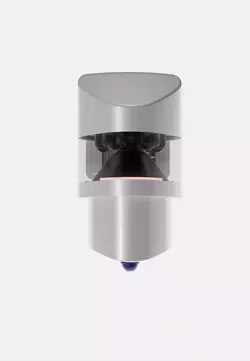

A “deterrence pod” by Sauron, a home security system, is seen on top of a garage in Miami Beach.

By Nitasha Tiku

In the future, your home will feel as safe from intruders as a state-of-the-art military base.

Cameras and sensors surveil the perimeter, scanning bystanders’ faces for potential threats. Drones from a “deterrence pod” scare off trespassers by projecting a search light over any suspicious movements. A virtual view of the home is rendered in 3D and updated in real-time, just like Tesla’s digital display. And private security agents monitor alerts from a central hub.

This is the vision of home security pitched by Sauron, a new Silicon Valley start-up boasting a wait list of tech CEOs and venture capitalists.

Co-founder Kevin Hartz, a tech entrepreneur and former partner at Peter Thiel’s venture firm Founders Fund, named the company after the villain in J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings,” a disembodied evil spirit, depicted as a fiery, all-seeing eye in the sky.

“It’s a little overt, a little tongue-in-cheek,” but sends the right message, Hartz said. “The bad people, they know they’re being watched.”

Hartz and co-founder Jack Abraham, said they were driven to start the company after incidents at their homes in San Francisco’s Presidio Terrace, an affluent, gated cul-de-sac once home to politicians such as Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-California), and Miami Beach, respectively. Hartz said his security system failed to alert him and his wife when an intruder rang their doorbell and tried to enter their home late at night.

By incorporating technology developed for autonomous vehicles, robotics and border security, Sauron has built a supercharged burglar alarm, Hartz argued.

The concept has resonated in Bay Area tech circles, where crime in San Francisco is a constant subject on tech podcasts, social media and executive group chats. While statistics from the San Francisco Police Department from October show that property crime and car theft has dropped in 2024 and that the homicide rate sits at a five-year low, the data has done little to appease the public’s fears.

Last month, San Francisco elected a mayor who ran on a platform of enhancing public safety and passed a proposition allowing the police more leeway to surveil residents. Around the country, voters have responded to similar perceptions of danger by rolling back police reforms instituted during the George Floyd protests.

“We had this kind of social experiment not to prosecute criminals, and you had the open-air drug markets and things of that nature,” Hartz said, comparing the sense of “lawlessness” with New York in the 1970s.

In Silicon Valley circles, these fears have inspired entrepreneurs to reframe commercial tech tools — such as drones and facial recognition technology — as a solution to safety woes for the military, law enforcement and individuals.

From left, Sauron co-founders Vasu Raman, Kevin Hartz and Jack Abraham.

For many tech elites, security is both a national priority and a growing concern in their personal lives.

“Crime prevention, detection, and response, as we know it, needs to change,” Andreessen Horowitz investment partner David Ulevitch wrote in a blog post last year titled “The Superhero Stack,” extolling the firm’s investment in “technology-enabled public safety” companies. These include start-ups partnering with police departments around the country, such as drone manufacturer Skydio and Flock Safety, which sells license plate readers.

After the presidential election last month, the start-up incubator Y Combinator put out a request for “public safety technology” companies, such as those that produce tools that facilitate a neighborhood watch or technology that uses computer vision to identify “suspicious activities or people in distress from video feeds.”

“We all deserve to be safe in our homes and while walking around on our streets,” Y Combinator president Garry Tan said in a YouTube Short video soliciting applications. “This is a basic thing civilization should afford its citizens. Start-ups are already on the case.”

While Hartz and his family are devoted to the city, not all of his friends see the wisdom in staying put. In a meeting with Thiel after the pandemic, he was aghast that the couple had stayed in San Francisco. “I saw a look of sadness and pity, like, ‘My god!’ you know,” Hartz said.

Sauron has raised $18 million in funding from executives behind Flock Safety and Palantir, the data analytics firm, defense tech investors such as 8VC, a venture firm started by Palantir co-founder Joe Lonsdale. Some backing comes from Abraham’s start-up lab, Atomic, and Hartz’s investment firm A*.

One of Sauron’s “deterrence pods” that are meant to be mounted outside the home.

The pods are meant to use drones eventually, although it has not been figure out how.

Sauron is targeting homeowners at the high end of the real estate market, beginning with a private event at Abraham’s home on Thursday, during Art Basel Miami Beach, the annual art exhibition that attracts collectors from around the world. The company plans to launch in San Francisco early next year, before expanding to Los Angeles and Miami.

Hartz said part of his motivation to move into home security was watching progress speed ahead in arenas such as self-driving cars while once-promising visions of domestic life, such as the smart home, languished. Big Tech companies haven’t deployed tools such as facial recognition as aggressively as Hartz would like.

“If somebody comes onto my property, I feel like I should know who that is,” Hartz said.

Meanwhile, mass market home-alarm systems, have a poor track record of false positives, leading dispatchers to deprioritize alerts, Hartz said.

In recent years massive investments have driven down the cost of drones, high-resolution cameras and lidar sensors, which use light detection to create 3D maps. Sauron uses low-cost hardware and tools like facial recognition, combined with custom-built software adapted for residential use. For facial recognition, it will use a third-party service called Paravision, a company backed by Atomic. Paravision began as a photo storage app called Everalbum, which was temporarily banned from Apple’s App Store for spamming user contacts, and later settled with the Federal Trade Commission over failing to inform users about the pivot.

Vasu Raman, co-founder and head of engineering at Sauron, uses an iPad to demonstrate Sauron’s home security system.

Other parts of the system are in flux, which is not unusual for a start-up. A couple of weeks before the demo, Hartz was still toying with the idea of whether Sauron should offer a virtual concierge that sounded like a robot butler, minus the robot. And he declined to offer any specific price range for the service.

Sauron is still figuring out how to incorporate drones, but it is already imagining more aggressive countermeasures, Hartz said. “Is it a machine that could take out a bad actor with a bullet or something?”

But Hartz also acknowledged that the tech crowd can be prone to apocalyptic thinking, particularly during times of economic upheaval and social unrest.

At tech dinner parties after the Great Recession, Hartz said discussion sometimes turned to best practices for fleeing the United States. In a scenario where someone acquired citizenship and a residency in New Zealand and had a pilot fly them there to safety, “people were talking about whether or not you kill the pilot of your plane because the pilot could harm your family,” he said.

The Sauron co-founder responsible for building its technology, head of engineering Vasu Raman, has a more communal view on home security.

A contractor installs a Sauron pod.

“I love cities, and I love the feeling of community within the crowd,” said Raman, who grew up in Mumbai and also experienced an attempted break-in at her home in San Francisco’s Mission neighborhood in the last year. “You get on a bus and people look out for each other mostly. They make sure you can get out when it’s your turn. They give up their seat to you.”

She thinks the dystopian view on San Francisco stems from a feeling of helplessness. Raman prefers to think of the adage: Good fences make good neighbors.

“If people are secure in their own homes, you can really lean into that community and start to build those relationships,” she said.