Millions of kids are missing weeks of school as attendance tanks across the US

Associated Press (archive.ph)

By Bianca Vázquez Toness

2023-08-11

SPRINGFIELD, Mass. – When in-person school resumed after pandemic closures, Rousmery Negrón and her 11-year-old son both noticed a change: School seemed less welcoming.

Parents were no longer allowed in the building without appointments, she said, and punishments were more severe. Everyone seemed less tolerant, more angry. Negrón's son told her he overheard a teacher mocking his learning disabilities, calling him an ugly name

Her son didn’t want to go to school anymore. And she didn’t feel he was safe there.

He would end up missing more than five months of sixth grade.

Rousmery Negrón stands with her son at home in Springfield, Mass., on Thursday, Aug. 3, 2023. When in-person school resumed after pandemic closures, Negrón and her son both noticed a change: School seemed less welcoming and everyone seemed less tolerant, more angry. He would end up missing more than five months of sixth grade. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

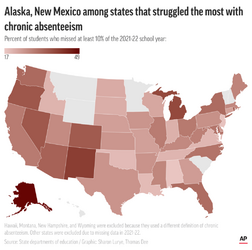

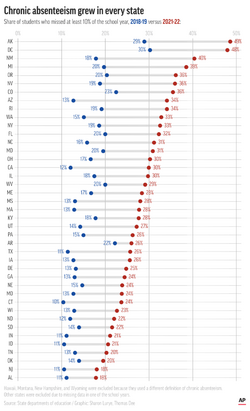

Across the country, students have been absent at record rates since schools reopened during the pandemic. More than a quarter of students missed at least 10% of the 2021-22 school year, making them chronically absent, according to the most recent data available. Before the pandemic, only 15% of students missed that much school.

All told, an estimated 6.5 million additional students became chronically absent, according to the data, which was compiled by Stanford University education professor Thomas Dee in partnership with The Associated Press. Taken together, the data from 40 states and Washington, D.C., provides the most comprehensive accounting of absenteeism nationwide. Absences were more prevalent among Latino, Black and low-income students, according to Dee’s analysis.

The absences come on top of time students missed during school closures and pandemic disruptions. They cost crucial classroom time as schools work to recover from massive learning setbacks.

Absent students miss out not only on instruction but also on all the other things schools provide — meals, counseling, socialization. In the end, students who are chronically absent — missing 18 or more days a year, in most places — are at higher risk of not learning to read and eventually dropping out.

“The long-term consequences of disengaging from school are devastating. And the pandemic has absolutely made things worse and for more students,” said Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, a nonprofit addressing chronic absenteeism.

In seven states, the rate of chronically absent kids doubled for the 2021-22 school year, from 2018-19, before the pandemic. Absences worsened in every state with available data — notably, the analysis found growth in chronic absenteeism did not correlate strongly with state COVID rates.

Kids are staying home for myriad reasons — finances, housing instability, illness, transportation issues, school staffing shortages, anxiety, depression, bullying and generally feeling unwelcome at school.

And the effects of online learning linger: School relationships have frayed, and after months at home, many parents and students don't see the point of regular attendance.

“For almost two years, we told families that school can look different and that schoolwork could be accomplished in times outside of the traditional 8-to-3 day. Families got used to that,” said Elmer Roldan, of Communities in Schools of Los Angeles, which helps schools follow up with absent students.

When classrooms closed in March 2020, Negrón in some ways felt relieved her two sons were home in Springfield. Since the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut, Negrón, who grew up in Puerto Rico, had become convinced mainland American schools were dangerous.

A year after in-person instruction resumed, she said, staff placed her son in a class for students with disabilities, citing hyperactive and distracted behavior. He felt unwelcome and unsafe. Now, it seemed to Negrón, there was danger inside school, too.

“He needs to learn,” said Negrón, a single mom who works as a cook at another school. “He’s very intelligent. But I’m not going to waste my time, my money on uniforms, for him to go to a school where he’s just going to fail.”

For people who've long studied chronic absenteeism, the post-COVID era feels different. Some of the things that prevent students from getting to school are consistent — illness, economic distress — but “something has changed,” said Todd Langager, who helps San Diego County schools address absenteeism. He sees students who already felt unseen, or without a caring adult at school, feel further disconnected.

Alaska led in absenteeism, with 48.6% of students missing significant amounts of school. Alaska Native students’ rate was higher, 56.5%.

Those students face poverty and a lack of mental health services, as well as a school calendar that isn’t aligned to traditional hunting and fishing activities, said Heather Powell, a teacher and Alaska Native. Many students are raised by grandparents who remember the government forcing Native children into boarding schools.

“Our families aren’t valuing education because it isn’t something that’s ever valued us,” Powell said.

In New York, Marisa Kosek said son James lost the relationships fostered at his school — and with them, his desire to attend class altogether. James, 12, has autism and struggled first with online learning and then with a hybrid model. During absences, he'd see his teachers in the neighborhood. They encouraged him to return, and he did.

But when he moved to middle school in another neighborhood, he didn’t know anyone. He lost interest and missed more than 100 days of sixth grade. The next year, his mom pushed for him to repeat the grade — and he missed all but five days.

His mother, a high school teacher, enlisted help: relatives, therapists, New York’s crisis unit. But James just wanted to stay home. He's anxious because he knows he's behind, and he's lost his stamina.

“Being around people all day in school and trying to act ‘normal’ is tiring,” said Kosek. She's more hopeful now that James has been accepted to a private residential school that specializes in students with autism.

Juan Ballina, right, stands with his mother, Carmen Ballina near their home Friday, July 28, 2023, in San Diego. Juan missed 94 days of school in 2022 because he didn't have a nurse to attend class with him to administer medication in case he seizes. (AP Photo/Gregory Bull)

Some students had chronic absences because of medical and staffing issues. Juan Ballina, 17, has epilepsy; a trained staff member must be nearby to administer medication in case of a seizure. But post-COVID-19, many school nurses retired or sought better pay in hospitals, exacerbating a nationwide shortage.

Last year, Juan's nurse was on medical leave. His school couldn’t find a substitute. He missed more than 90 days at his Chula Vista, California, high school.

“I was lonely,” Ballina said. “I missed my friends.”

Last month, school started again. So far, Juan's been there, with his nurse. But his mom, Carmen Ballina, said the effects of his absence persist: “He used to read a lot more. I don’t think he’s motivated anymore.”

Another lasting effect from the pandemic: Educators and experts say some parents and students have been conditioned to stay home at the slightest sign of sickness.

Renee Slater's daughter rarely missed school before the pandemic. But last school year, the straight-A middle schooler insisted on staying home 20 days, saying she just didn't feel well.

“As they get older, you can’t physically pick them up into the car — you can only take away privileges, and that doesn’t always work,” said Slater, who teaches in the rural California district her daughter attends. “She doesn’t dislike school, it’s just a change in mindset."

An empty elementary school classroom is seen on Tuesday, Aug. 17, 2021 in the Bronx borough of New York. Nationwide, students have been absent at record rates since schools reopened after COVID-forced closures. (AP Photo/Brittainy Newman, File)

Most states have yet to release attendance data from 2022-23, the most recent school year. Based on the few that have shared figures, it seems the chronic-absence trend may have long legs. In Connecticut and Massachusetts, chronic absenteeism remained double its pre-pandemic rate.

In Negrón’s hometown of Springfield, 39% of students were chronically absent last school year, an improvement from 50% the year before. Rates are higher for students with disabilities.

While Negrón's son was out of school, she said, she tried to stay on top of his learning. She picked up a weekly folder of worksheets and homework; he couldn’t finish because he didn’t know the material.

“He was struggling so much, and the situation was putting him in a down mood," Negrón said.

Last year, she filed a complaint asking officials to give her son compensatory services and pay for him to attend a private special education school. The judge sided with the district.

Now, she’s eyeing the new year with dread. Her son doesn’t want to return. Negrón said she'll consider it only if the district grants her request for him to study in a mainstream classroom with a personal aide. The district told AP it can't comment on individual student cases due to privacy considerations.

Negrón wishes she could homeschool her sons, but she has to work and fears they'd suffer from isolation.

“If I had another option, I wouldn’t send them to school,” she said.

AP education writer Sharon Lurye contributed from New Orleans; AP reporter Becky Bohrer contributed from Juneau. This story was reported and published in partnership with EdSource, a nonprofit newsroom that covers education in California. EdSource reporter Betty Márquez Rosales contributed reporting from Bakersfield.

The Associated Press education team receives support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

---

Why are more students chronically absent in California, U.S.? Study examines troubling trend

Los Angeles Times (archive.ph)

By Betty Márquez Rosales, Bianca Vázquez Toness, Howard Blume

2023-08-11 17:20:17.829GMT

Since the pandemic, the number of students across the country who are chronically absent — meaning they missed at least 10% of the school year — has nearly doubled to 13.6 million, according to estimates in a new study.

About 1.8 million of these students were from California, which saw its chronic absenteeism explode from about 12% in the school year before the COVID-19 pandemic to 30% in 2021-22, according to data compiled by Stanford University education professor Thomas S. Dee in partnership with the Associated Press. EdSource, a nonprofit newsroom that covers California education, analyzed California data.

California had among the highest increases in chronic absenteeism in the country. The percentages translate to about 1 million additional chronically absent California children when compared with the year before the pandemic. For students on a typical 180-day school calendar, missing 10% of the school year represents nearly one month — missed learning time that compounds the challenge of helping students recover academically and emotionally from the pandemic.

Data are not yet available for the 2022-23 school year, although limited information from some California school districts and two other states suggest attendance may not be greatly improving, Dee said.

The findings “should really be a kind of clarion call to learn more about exactly what is explaining this incredible growth,” he said.

Complex issues

Issues that contribute to chronic absenteeism can be multilayered.

Juan Ballina, 17, has epilepsy; a trained staff member must be nearby to administer medication in case of a seizure. But during the pandemic, many school nurses left their jobs, exacerbating shortages.

Last year, Juan’s nurse was on medical leave. His school couldn’t find a substitute. He missed more than 90 days at his Chula Vista high school.

“I was lonely,” Juan said. “I missed my friends.”

This year his school has a nurse and Juan is back in class, but the effect of his absences persists, his mother, Carmen Ballina, said: “He used to read a lot more. I don’t think he’s motivated anymore.”

When students were in remote learning, engagement from home was a major problem. Many students had computer or internet access problems or simply weren’t logging on often enough and for sustained periods. Distractions at home and family hardships made things worse.

Schools have used COVID relief and recovery funds to provide academic and mental health support, but these services work best for students who are in school. And as schools struggle to get students to class, the funding for such extra support is rapidly running out.

Compared with before the pandemic, absences worsened in every state with available data.

At the state level, Dee did not find a strong correlation between rates of absence and COVID-19 infection rates or COVID-19 safety policies, such as requiring or banning the use of masks. However, the lack of detail in the state-level data could have obscured measurable effects at the local level.

Dee concluded that while sickness may have contributed to the surge in chronic absenteeism, “it’s not really wholly explaining it … so the evidence is pointing to other substantive and enduring factors.”

Dee and other experts attribute the absences to factors including the emotional and financial fallout of pandemic-related deaths, access to school transportation, increased anxieties around the safety of attending school in person, and declines in youth mental health and academic engagement.

“The pandemic’s over, but if people lost family members, that matters,” said Hedy Chang, executive director of a chronic absenteeism initiative called Attendance Works. “That’s a lasting impact on a whole set of things, both emotional and economic.”

LAUSD steps up efforts

The Los Angeles Unified School District had a 40% chronic absentee rate in the 2021-22 school year — about 10 percentage points higher than the state’s. Alarmed by the numbers, officials accelerated an outreach campaign targeting students and their families — including those struggling with homelessness.

Although the data have not been officially reported by the state, Supt. Alberto Carvalho said internal record keeping shows a 10-percentage-point drop in chronic absenteeism during the 2022-23 school year, which would translate to a 30% chronic absenteeism rate.

Although Carvalho characterized this drop as an signature achievement, the rate remains higher than the 20% pre-pandemic level, a number that was already considered high.

As part of the district’s iAttend program, administrators, principals, attendance counselors and other staff knocked on 9,000 doors last school year to encourage families of chronically absent or unenrolled students to return to class. The next event is planned for Friday.

Elmer Roldan, executive director of Communities in Schools of Los Angeles, said the effects of online learning linger: School relationships have frayed, and after months at home, many parents and students don’t see the point of regular attendance.

“For almost two years, we told families that school can look different and that schoolwork could be accomplished in times outside of the traditional 8-to-3 day. Families got used to that,” he said.

The district’s grading policies also have changed, based on compassion during the pandemic and changes in academic philosophy. The district has entirely disconnected grades from attendance, turning in assignments on time and classroom behavior.

In promoting good attendance, the school system stresses the positives. Officials have ongoing supports for students, such as on-demand online tutoring and extra school days to catch up with assignments. But such assistance works best when students are in school.

Another issue confronting L.A. Unified and other state school systems is the financial burden of low attendance. California funds schools largely based on attendance rather than enrollment. Absent students ultimately mean less money to educate all and to pay for services and staff.

Rural district challenges

Many of California’s districts in small towns and rural regions faced high chronic absenteeism rates long before the pandemic and, according to an EdSource analysis, rural districts as a group have seen the sharpest increases since then.

Renee Slater’s daughter is a straight-A middle-school student and student council member in the Rio Bravo-Greeley Union School District in the Bakersfield area. Yet, she missed 20 days this past school year.

The eighth-grader had good attendance before the pandemic, but that changed when she began insisting on staying home more often than she ever had, her mother said.

“She’d just be like: ‘I don’t feel good today — I’m just gonna stay home,’” Slater said. “She doesn’t dislike school; it was just a change in mind-set. Like, you know, I can make it up.”

Slater, a district teacher, worries her daughter’s learning is suffering.

Their district’s chronic absenteeism rates rose to 21% during the 2021-22 school year, up from 8% in 2018-19.

Chang, of Attendance Works, said increased communication, including postcards and text messages that help connect to students and families, could help improve rates.

At Lodi Unified, a 28,000-student urban district in Central California, families will begin receiving a weekly letter with updates on school activities. The “Sunday night letters,” as they’re being referred to, were sparked in part by a tripling of chronic absenteeism rates to 39.2% in 2021-22.

Knocking on absent students’ doors to do wellness checks isn’t feasible in some rural districts, where students can live miles apart, educators said.

In Modoc, the state’s most northeastern county, distance leads to absences, Supt. Tom O’Malley said.

“If you need any kind of advanced services, if you’re a child who’s got some kind of a medical issue, you’re going to be gone a lot,” said O’Malley, who grew up in the area.

The nearly 900-student district experienced an increase of 15 percentage points in chronic absenteeism between the 2018-19 and 2021-22 school years.

“Our kids miss a lot of school, but you kind of have to,” he said. “There’s no way around it.”

Signs of continuing high absences

In Dee’s study, two states — Massachusetts and Connecticut — are reporting continued high absentee rates for the 2022-23 school year, a trend that also may be surfacing in California districts.

School Innovations and Achievement, a national attendance consulting firm that works with 29 of the California’s nearly 1,000 districts, estimated that the rate of chronic absenteeism could drop from 32.7% in 2021-22 to 30.5% in 2022-23 in these districts. The firm declined to share the names of districts, but said they reflect California’s diverse geographic regions, district sizes and student demographics.

“A lot of the feelings of safety, security and connectedness were broken and disrupted due to the pandemic, and so [students] are just now starting to build school-going habits and reestablishing connections at schools,” said Erica Peterson, the firm’s director of education and engagement.

This article was reported and written in partnership with EdSource, a nonprofit newsroom that covers education in California, and the Associated Press. Rosales writes for EdSource, Toness writes for the Associated Press, and Blume is a Times staff writer. Mallika Seshadri and Daniel J. Willis of EdSource and Cara Nixon, an EdSource intern, contributed to this report.

---

Higher Chronic Absenteeism Threatens Academic Recovery from the COVID-19 Pandemic

Thomas S. Dee

https://osf.io/bfg3p/ (archive.ph)

Associated Press (archive.ph)

By Bianca Vázquez Toness

2023-08-11

SPRINGFIELD, Mass. – When in-person school resumed after pandemic closures, Rousmery Negrón and her 11-year-old son both noticed a change: School seemed less welcoming.

Parents were no longer allowed in the building without appointments, she said, and punishments were more severe. Everyone seemed less tolerant, more angry. Negrón's son told her he overheard a teacher mocking his learning disabilities, calling him an ugly name

Her son didn’t want to go to school anymore. And she didn’t feel he was safe there.

He would end up missing more than five months of sixth grade.

Rousmery Negrón stands with her son at home in Springfield, Mass., on Thursday, Aug. 3, 2023. When in-person school resumed after pandemic closures, Negrón and her son both noticed a change: School seemed less welcoming and everyone seemed less tolerant, more angry. He would end up missing more than five months of sixth grade. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

Across the country, students have been absent at record rates since schools reopened during the pandemic. More than a quarter of students missed at least 10% of the 2021-22 school year, making them chronically absent, according to the most recent data available. Before the pandemic, only 15% of students missed that much school.

All told, an estimated 6.5 million additional students became chronically absent, according to the data, which was compiled by Stanford University education professor Thomas Dee in partnership with The Associated Press. Taken together, the data from 40 states and Washington, D.C., provides the most comprehensive accounting of absenteeism nationwide. Absences were more prevalent among Latino, Black and low-income students, according to Dee’s analysis.

The absences come on top of time students missed during school closures and pandemic disruptions. They cost crucial classroom time as schools work to recover from massive learning setbacks.

Absent students miss out not only on instruction but also on all the other things schools provide — meals, counseling, socialization. In the end, students who are chronically absent — missing 18 or more days a year, in most places — are at higher risk of not learning to read and eventually dropping out.

“The long-term consequences of disengaging from school are devastating. And the pandemic has absolutely made things worse and for more students,” said Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, a nonprofit addressing chronic absenteeism.

In seven states, the rate of chronically absent kids doubled for the 2021-22 school year, from 2018-19, before the pandemic. Absences worsened in every state with available data — notably, the analysis found growth in chronic absenteeism did not correlate strongly with state COVID rates.

Kids are staying home for myriad reasons — finances, housing instability, illness, transportation issues, school staffing shortages, anxiety, depression, bullying and generally feeling unwelcome at school.

And the effects of online learning linger: School relationships have frayed, and after months at home, many parents and students don't see the point of regular attendance.

“For almost two years, we told families that school can look different and that schoolwork could be accomplished in times outside of the traditional 8-to-3 day. Families got used to that,” said Elmer Roldan, of Communities in Schools of Los Angeles, which helps schools follow up with absent students.

When classrooms closed in March 2020, Negrón in some ways felt relieved her two sons were home in Springfield. Since the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut, Negrón, who grew up in Puerto Rico, had become convinced mainland American schools were dangerous.

A year after in-person instruction resumed, she said, staff placed her son in a class for students with disabilities, citing hyperactive and distracted behavior. He felt unwelcome and unsafe. Now, it seemed to Negrón, there was danger inside school, too.

“He needs to learn,” said Negrón, a single mom who works as a cook at another school. “He’s very intelligent. But I’m not going to waste my time, my money on uniforms, for him to go to a school where he’s just going to fail.”

For people who've long studied chronic absenteeism, the post-COVID era feels different. Some of the things that prevent students from getting to school are consistent — illness, economic distress — but “something has changed,” said Todd Langager, who helps San Diego County schools address absenteeism. He sees students who already felt unseen, or without a caring adult at school, feel further disconnected.

Alaska led in absenteeism, with 48.6% of students missing significant amounts of school. Alaska Native students’ rate was higher, 56.5%.

Those students face poverty and a lack of mental health services, as well as a school calendar that isn’t aligned to traditional hunting and fishing activities, said Heather Powell, a teacher and Alaska Native. Many students are raised by grandparents who remember the government forcing Native children into boarding schools.

“Our families aren’t valuing education because it isn’t something that’s ever valued us,” Powell said.

In New York, Marisa Kosek said son James lost the relationships fostered at his school — and with them, his desire to attend class altogether. James, 12, has autism and struggled first with online learning and then with a hybrid model. During absences, he'd see his teachers in the neighborhood. They encouraged him to return, and he did.

But when he moved to middle school in another neighborhood, he didn’t know anyone. He lost interest and missed more than 100 days of sixth grade. The next year, his mom pushed for him to repeat the grade — and he missed all but five days.

His mother, a high school teacher, enlisted help: relatives, therapists, New York’s crisis unit. But James just wanted to stay home. He's anxious because he knows he's behind, and he's lost his stamina.

“Being around people all day in school and trying to act ‘normal’ is tiring,” said Kosek. She's more hopeful now that James has been accepted to a private residential school that specializes in students with autism.

Juan Ballina, right, stands with his mother, Carmen Ballina near their home Friday, July 28, 2023, in San Diego. Juan missed 94 days of school in 2022 because he didn't have a nurse to attend class with him to administer medication in case he seizes. (AP Photo/Gregory Bull)

Some students had chronic absences because of medical and staffing issues. Juan Ballina, 17, has epilepsy; a trained staff member must be nearby to administer medication in case of a seizure. But post-COVID-19, many school nurses retired or sought better pay in hospitals, exacerbating a nationwide shortage.

Last year, Juan's nurse was on medical leave. His school couldn’t find a substitute. He missed more than 90 days at his Chula Vista, California, high school.

“I was lonely,” Ballina said. “I missed my friends.”

Last month, school started again. So far, Juan's been there, with his nurse. But his mom, Carmen Ballina, said the effects of his absence persist: “He used to read a lot more. I don’t think he’s motivated anymore.”

Another lasting effect from the pandemic: Educators and experts say some parents and students have been conditioned to stay home at the slightest sign of sickness.

Renee Slater's daughter rarely missed school before the pandemic. But last school year, the straight-A middle schooler insisted on staying home 20 days, saying she just didn't feel well.

“As they get older, you can’t physically pick them up into the car — you can only take away privileges, and that doesn’t always work,” said Slater, who teaches in the rural California district her daughter attends. “She doesn’t dislike school, it’s just a change in mindset."

An empty elementary school classroom is seen on Tuesday, Aug. 17, 2021 in the Bronx borough of New York. Nationwide, students have been absent at record rates since schools reopened after COVID-forced closures. (AP Photo/Brittainy Newman, File)

Most states have yet to release attendance data from 2022-23, the most recent school year. Based on the few that have shared figures, it seems the chronic-absence trend may have long legs. In Connecticut and Massachusetts, chronic absenteeism remained double its pre-pandemic rate.

In Negrón’s hometown of Springfield, 39% of students were chronically absent last school year, an improvement from 50% the year before. Rates are higher for students with disabilities.

While Negrón's son was out of school, she said, she tried to stay on top of his learning. She picked up a weekly folder of worksheets and homework; he couldn’t finish because he didn’t know the material.

“He was struggling so much, and the situation was putting him in a down mood," Negrón said.

Last year, she filed a complaint asking officials to give her son compensatory services and pay for him to attend a private special education school. The judge sided with the district.

Now, she’s eyeing the new year with dread. Her son doesn’t want to return. Negrón said she'll consider it only if the district grants her request for him to study in a mainstream classroom with a personal aide. The district told AP it can't comment on individual student cases due to privacy considerations.

Negrón wishes she could homeschool her sons, but she has to work and fears they'd suffer from isolation.

“If I had another option, I wouldn’t send them to school,” she said.

AP education writer Sharon Lurye contributed from New Orleans; AP reporter Becky Bohrer contributed from Juneau. This story was reported and published in partnership with EdSource, a nonprofit newsroom that covers education in California. EdSource reporter Betty Márquez Rosales contributed reporting from Bakersfield.

The Associated Press education team receives support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

---

Why are more students chronically absent in California, U.S.? Study examines troubling trend

Los Angeles Times (archive.ph)

By Betty Márquez Rosales, Bianca Vázquez Toness, Howard Blume

2023-08-11 17:20:17.829GMT

Since the pandemic, the number of students across the country who are chronically absent — meaning they missed at least 10% of the school year — has nearly doubled to 13.6 million, according to estimates in a new study.

About 1.8 million of these students were from California, which saw its chronic absenteeism explode from about 12% in the school year before the COVID-19 pandemic to 30% in 2021-22, according to data compiled by Stanford University education professor Thomas S. Dee in partnership with the Associated Press. EdSource, a nonprofit newsroom that covers California education, analyzed California data.

California had among the highest increases in chronic absenteeism in the country. The percentages translate to about 1 million additional chronically absent California children when compared with the year before the pandemic. For students on a typical 180-day school calendar, missing 10% of the school year represents nearly one month — missed learning time that compounds the challenge of helping students recover academically and emotionally from the pandemic.

Data are not yet available for the 2022-23 school year, although limited information from some California school districts and two other states suggest attendance may not be greatly improving, Dee said.

The findings “should really be a kind of clarion call to learn more about exactly what is explaining this incredible growth,” he said.

Complex issues

Issues that contribute to chronic absenteeism can be multilayered.

Juan Ballina, 17, has epilepsy; a trained staff member must be nearby to administer medication in case of a seizure. But during the pandemic, many school nurses left their jobs, exacerbating shortages.

Last year, Juan’s nurse was on medical leave. His school couldn’t find a substitute. He missed more than 90 days at his Chula Vista high school.

“I was lonely,” Juan said. “I missed my friends.”

This year his school has a nurse and Juan is back in class, but the effect of his absences persists, his mother, Carmen Ballina, said: “He used to read a lot more. I don’t think he’s motivated anymore.”

When students were in remote learning, engagement from home was a major problem. Many students had computer or internet access problems or simply weren’t logging on often enough and for sustained periods. Distractions at home and family hardships made things worse.

Schools have used COVID relief and recovery funds to provide academic and mental health support, but these services work best for students who are in school. And as schools struggle to get students to class, the funding for such extra support is rapidly running out.

Compared with before the pandemic, absences worsened in every state with available data.

At the state level, Dee did not find a strong correlation between rates of absence and COVID-19 infection rates or COVID-19 safety policies, such as requiring or banning the use of masks. However, the lack of detail in the state-level data could have obscured measurable effects at the local level.

Dee concluded that while sickness may have contributed to the surge in chronic absenteeism, “it’s not really wholly explaining it … so the evidence is pointing to other substantive and enduring factors.”

Dee and other experts attribute the absences to factors including the emotional and financial fallout of pandemic-related deaths, access to school transportation, increased anxieties around the safety of attending school in person, and declines in youth mental health and academic engagement.

“The pandemic’s over, but if people lost family members, that matters,” said Hedy Chang, executive director of a chronic absenteeism initiative called Attendance Works. “That’s a lasting impact on a whole set of things, both emotional and economic.”

LAUSD steps up efforts

The Los Angeles Unified School District had a 40% chronic absentee rate in the 2021-22 school year — about 10 percentage points higher than the state’s. Alarmed by the numbers, officials accelerated an outreach campaign targeting students and their families — including those struggling with homelessness.

Although the data have not been officially reported by the state, Supt. Alberto Carvalho said internal record keeping shows a 10-percentage-point drop in chronic absenteeism during the 2022-23 school year, which would translate to a 30% chronic absenteeism rate.

Although Carvalho characterized this drop as an signature achievement, the rate remains higher than the 20% pre-pandemic level, a number that was already considered high.

As part of the district’s iAttend program, administrators, principals, attendance counselors and other staff knocked on 9,000 doors last school year to encourage families of chronically absent or unenrolled students to return to class. The next event is planned for Friday.

Elmer Roldan, executive director of Communities in Schools of Los Angeles, said the effects of online learning linger: School relationships have frayed, and after months at home, many parents and students don’t see the point of regular attendance.

“For almost two years, we told families that school can look different and that schoolwork could be accomplished in times outside of the traditional 8-to-3 day. Families got used to that,” he said.

The district’s grading policies also have changed, based on compassion during the pandemic and changes in academic philosophy. The district has entirely disconnected grades from attendance, turning in assignments on time and classroom behavior.

In promoting good attendance, the school system stresses the positives. Officials have ongoing supports for students, such as on-demand online tutoring and extra school days to catch up with assignments. But such assistance works best when students are in school.

Another issue confronting L.A. Unified and other state school systems is the financial burden of low attendance. California funds schools largely based on attendance rather than enrollment. Absent students ultimately mean less money to educate all and to pay for services and staff.

Rural district challenges

Many of California’s districts in small towns and rural regions faced high chronic absenteeism rates long before the pandemic and, according to an EdSource analysis, rural districts as a group have seen the sharpest increases since then.

Renee Slater’s daughter is a straight-A middle-school student and student council member in the Rio Bravo-Greeley Union School District in the Bakersfield area. Yet, she missed 20 days this past school year.

The eighth-grader had good attendance before the pandemic, but that changed when she began insisting on staying home more often than she ever had, her mother said.

“She’d just be like: ‘I don’t feel good today — I’m just gonna stay home,’” Slater said. “She doesn’t dislike school; it was just a change in mind-set. Like, you know, I can make it up.”

Slater, a district teacher, worries her daughter’s learning is suffering.

Their district’s chronic absenteeism rates rose to 21% during the 2021-22 school year, up from 8% in 2018-19.

Chang, of Attendance Works, said increased communication, including postcards and text messages that help connect to students and families, could help improve rates.

At Lodi Unified, a 28,000-student urban district in Central California, families will begin receiving a weekly letter with updates on school activities. The “Sunday night letters,” as they’re being referred to, were sparked in part by a tripling of chronic absenteeism rates to 39.2% in 2021-22.

Knocking on absent students’ doors to do wellness checks isn’t feasible in some rural districts, where students can live miles apart, educators said.

In Modoc, the state’s most northeastern county, distance leads to absences, Supt. Tom O’Malley said.

“If you need any kind of advanced services, if you’re a child who’s got some kind of a medical issue, you’re going to be gone a lot,” said O’Malley, who grew up in the area.

The nearly 900-student district experienced an increase of 15 percentage points in chronic absenteeism between the 2018-19 and 2021-22 school years.

“Our kids miss a lot of school, but you kind of have to,” he said. “There’s no way around it.”

Signs of continuing high absences

In Dee’s study, two states — Massachusetts and Connecticut — are reporting continued high absentee rates for the 2022-23 school year, a trend that also may be surfacing in California districts.

School Innovations and Achievement, a national attendance consulting firm that works with 29 of the California’s nearly 1,000 districts, estimated that the rate of chronic absenteeism could drop from 32.7% in 2021-22 to 30.5% in 2022-23 in these districts. The firm declined to share the names of districts, but said they reflect California’s diverse geographic regions, district sizes and student demographics.

“A lot of the feelings of safety, security and connectedness were broken and disrupted due to the pandemic, and so [students] are just now starting to build school-going habits and reestablishing connections at schools,” said Erica Peterson, the firm’s director of education and engagement.

This article was reported and written in partnership with EdSource, a nonprofit newsroom that covers education in California, and the Associated Press. Rosales writes for EdSource, Toness writes for the Associated Press, and Blume is a Times staff writer. Mallika Seshadri and Daniel J. Willis of EdSource and Cara Nixon, an EdSource intern, contributed to this report.

---

Higher Chronic Absenteeism Threatens Academic Recovery from the COVID-19 Pandemic

Thomas S. Dee

https://osf.io/bfg3p/ (archive.ph)