L | A (Translated with ChatGPT)

By Ma Zongtian

Simplified Chinese Characters with Traditional corrections

Due to the differences in written characters between the two sides (Taiwan and Mainland China), people visiting relatives in Mainland China might encounter the following confusion:

A flour shop (面粉店) – does it sell flour (麵粉), or is this a cosmetics store (面粉 can also refer to face powder)? "午會" – does this refer to a dance party (舞會), or a meeting held at noon (中午開會)? Which "丁" is it – is it "叮" (to ring), "丁" (a small object or person), "釘" (nail), or "盯" (to stare)? Which "采" is it – is it "採" (to pick), "踩" (to step on), "睬" (to pay attention to), "彩" (color), or "綵" (colored silk)?

"Ha! Teacher, you wrote the wrong character."

In December of last year, several children from mainland China visiting Taiwan were surprised to see "大庆油田" (Daqing Oilfield) written in large characters on the blackboard during their visit to a junior high school in Taipei, experiencing local classes.

“It has one more dot in it,” said one enthusiastic child. Little did she know that the teacher had originally intended not to write in simplified characters during class, and the extra dots in “庆” (qìng, celebrate) were deliberately included for their benefit, yet it still left the child disappointed.

The phenomenon of different written characters across the Taiwan Strait quietly occurs in our daily lives.

In April of this year, the Secretary-General of the Straits Exchange Foundation, Qiu Jinyi, traveled to the mainland to discuss matters regarding registered mail and document verification, negotiating with the mainland's Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits. They agreed that to "respect the language habits of both sides," documents would be signed in both simplified and traditional characters.

Since the opening up of cross-strait exchanges, many people have received letters from relatives and friends on the mainland entirely written in simplified characters, occasionally expressing their confusion about how to read them.

As exchanges between the two sides increase and more mainland publications circulate in Taiwan, many people often feel that mainland simplified books are like 'incomprehensible texts' that are difficult to understand.

Calligraphy art best showcases the distinct textures and complete symmetry of traditional characters. But is understanding traditional characters merely the privilege of calligraphers?

Half a Family, Instant Noodles?!

For the people visiting family in mainland China, the first thing that greets them upon passing through customs is the sight of Simplified Chinese characters everywhere. For those coming from Taiwan, although these Simplified characters and their usages are common, there is always a sense of entering a different environment.

For example: 搞活經濟 (revitalize the economy), 抓好物價 (stabilize prices), 通過函調 (conduct external inquiries via correspondence), 半邊家庭 (single-parent family), 超常兒童 (gifted children), 立交橋 (interchange), 方便麵 (instant noodles), and so on...

Lin Xinzhang, a former famous baseball coach in Taiwan, is now training baseball teams in the mainland. In the Taiwanese baseball community, he is often referred to as "Coach Xin" (信将), but now he is called "Coach Lin" (林指)

When friends from Taiwan visit him in the mainland and sit in the baseball stadium, listening to players from all around shout things like “来一棒” (let’s get a hit), “本壘跑” (home run), “好打好投” (good hitting and good pitching), they often find themselves “hearing but not understanding.”

There are even more characters that are hard to understand. For example, the character "干 (gān)" in mainland China can mean "to do," but it can also mean "干 (gān)" (dry) or "淦 (gàn)" (to be annoyed). "卜" (bǔ) can refer to "divination" (占卜, zhānbǔ) or "radish" (萝卜, luóbo); Is "麵粉" (miànfěn) for selling cosmetics or for opening a noodle shop? Is 开午会 (kāi wǔ huì) mean holding a meeting at noon or dancing?

Some describe the experience of reading simplified Chinese characters in the mainland as akin to being in the mainland itself: 亲 (qīn, meaning relation) without "见" (jiàn, meaning "to see") becomes a relationship without the act of seeing, 爱 (ài, love) without "心" (xīn, heart) lacks emotional depth, 产 (chǎn, to produce) that does not give birth, and the restroom "开关" (kāiguān, switch) that has no door.

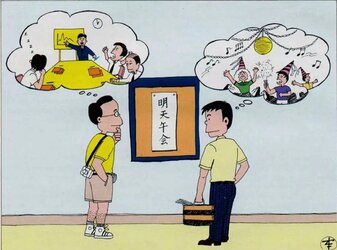

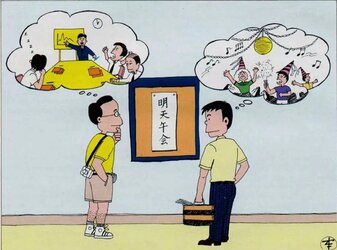

Is '明天午會' (tomorrow's noon meeting) about a dance party? Or is it a meeting at noon tomorrow? The visitors from Taiwan can only ask their hometown folks.

Chinese Characters as Sacrificial Lambs

Such criticism is certainly sharp, but since the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) implemented language reform thirty-seven years ago, the use of simplified characters in mainland China has reached a point that necessitates re-examination.

In April of the year before last, Liu Bin, the director of the mainland's "National Language and Writing Work Committee," pointed out that the prominent language issues currently faced in mainland China are the rampant creation of characters and words, the deliberate use of traditional characters, and a significant number of misspellings.

The phenomenon of creating and using characters arbitrarily has a long history. Gong Pengcheng, director of the Cultural Education Department of the Mainland Affairs Council, believes that when the CCP initially promoted language reform, it did not consider the systematization and rationality of Chinese characters, which has led to the current root of the arbitrary creation of characters in society.

The CCP began promoting simplified characters in 1956. At that time, the proposed "Chinese Character Simplification Plan" listed more than two thousand simplified characters, which are now the standard for simplified characters in mainland China.

Mao Zedong once said: "Writing must be reformed; it should move towards a common phonetic direction of world writing." He believed that simplification was an inevitable historical path, aimed at preparing for the phoneticization of Chinese characters. This is related to the environment at the beginning of the Republic of China.

From the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic, from the Opium War to the eight-year Anti-Japanese War, our country experienced many setbacks under the invasion of foreign powers, leading to a weakened national strength and worsened living conditions.

Intellectuals seeking to strengthen the nation were very concerned, with some attributing blame to Chinese culture for being inferior, subsequently determining that the square-shaped Chinese characters could not compete with the phonetic letters of Western writing.

The significant rise in illiteracy was also attributed to the incomprehensibility of Chinese characters, hence the loud calls for language reform. The intellectuals of the May Fourth Movement, such as Qian Xuantong, Lu Xun, and Hu Shi, were all advocates for simplified characters.

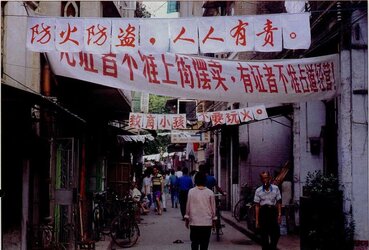

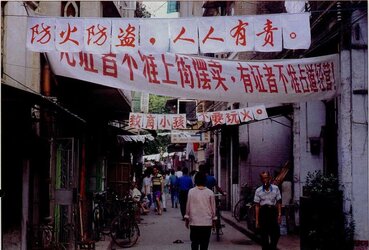

Looking at the various street signs in the alleys of Guangzhou's bustling area, visitors from Taiwan only feel that 'many of the characters are written incorrectly.'

Simplified Characters are like the Red Guards!

Language and writing are tools for communication among people. When they develop over time, it is necessary to establish appropriate norms and reviews under reasonable circumstances. However, it is indeed rare in history for a regime, like the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), to concentrate a large number of intellectuals just a few years after seizing power to fully promote a policy of Chinese character simplification.

How significant is the impact of simplified characters? Professor Huang Yongwu from Taipei Municipal Teachers College once described simplified characters as "the Red Guards," referring to the harm they pose to Chinese culture.

He believes that simplified characters undermine the inherent structural system of Chinese writing and lack superior academic conditions. As a result, future generations may be unable to understand Chinese characters and become estranged from traditional culture, with the damage being comparable to that caused by the Red Guards.

For example, he points out that the character "葉" (yè, leaf) contains the "艸" (cǎo, grass) radical, which indicates it belongs to the plant category and is immediately recognizable.

Meanwhile, characters sharing the same phonetic component, such as "成薄片狀" (chéng bópiàn zhuàng, "to become thin slices"), have phonetic elements that convey meaning.

Other characters that share the same phonetic component include "諜" (dié, spy), "碟" (dié, dish), "蝶" (dié, butterfly), and "喋" (dié, chatter), where the left side represents the category of the object and the right side conveys the sound and meaning.

Unfortunately, writing "葉" as "叶" not only disrupts the radical but also loses the semantic system of "薄片狀草木" (bópiàn zhuàng cǎomù, "thin slice plants") within the character system.

Similarly, when "髮" (fà, hair) is simplified to "发", it raises ambiguity: does "秀發" (xiùfà, beautiful hair) refer to beautiful hair or smart hair? What about "叶韻" (yè yùn, rhyme of leaves) — does it refer to "ancient poetry rhyme" or "the entering tone of leaves"?

Research by Professor Huang Peirong from National Taiwan University also points out issues with mainland China's language reform, such as confused characters — like "嘆" (tàn, sigh), "漢" (hàn, Han), "勸" (quàn, persuade), "觀" (guān, observe), and "戲" (xì, play) all belonging to the "又" (yòu) radical — and destruction of structure — for instance, "華" (huá, splendid) simplified to "华," "書" (shū, book) to "书," "堯" (yáo, Yao) to "尧," and loss of root words — like "構" (gòu, structure) simplified to "构."

These issues complicate learning and hinder contemporary understanding of ancient texts, negatively impacting cultural transmission.

Carefully examining these signs, the main problems of word usage in mainland society—such as the arbitrary creation of new characters, the use of simplified characters, and the frequent misspellings—are all evident.

Teaching Efficiency is Unrelated to Complexity

However, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) argues that there are many illiterate individuals in mainland China, and it is "impossible to demand that everyone understand the profound traditional characters."

Professor Li Xinkui from Sun Yat-sen University in Guangdong believes that cultural progress varies; common villagers do not need to know so many difficult or obscure characters. Practical characters for daily life are sufficient. When they have enough knowledge or a desire to learn and truly wish to understand the past and present, it is not too late to learn traditional characters.

Professor Li points out the main motivation behind the CCP's implementation of the simplification scheme: that simplified characters facilitate the popularization of education. However, to this day, many harsh realities have dealt a blow to the simplification policy.

"Taiwan does not follow the path of simplification, and its literacy rate exceeds ninety-five percent; after over thirty years of promoting simplified characters in mainland China, it appears that illiteracy has not decreased," says Huang Peirong.

Moreover, in terms of teaching efficiency, simplified characters may not be superior to traditional characters.

Research by Professor Zheng Zhaoming from National Taiwan University indicates that learning characters involves "the differentiation of words" and "the identification of meanings," both of which are unrelated to the complexity of strokes.

Characters with complex and simple strokes may be similarly difficult to distinguish, such as "傅" (fù, to teach) and "傳" (chuán, to transmit), or "已" (yǐ, already) and "己" (jǐ, self). Conversely, they may be easily distinguished due to their differences, like "補" (bǔ, to supplement) and "馳" (chí, to gallop), or "田" (tián, field) and "戶" (hù, door).

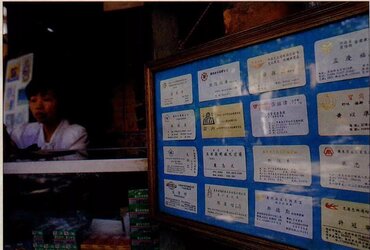

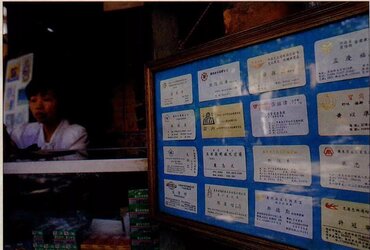

A business card printed by a shop in Guangzhou is entirely in traditional characters. Is it just a show of style?

The Rise of the 'New Cultural Class'?

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) believes that only those studying literature and history or practicing calligraphy need to learn traditional characters, a view that is open to debate. Huang Peirong points out that breaking down class barriers and allowing the proletariat to rise was originally a hallmark of the CCP regime. Today, being able to read traditional characters has become a new kind of "cultural class."

Another reason the mainland does not think simplified characters hinder cultural transmission is that for over thirty years, many ancient poetry and literature publications, such as "Dream of the Red Chamber," "Commentaries on Records of the Grand Historian," and "Three Hundred Tang Poems," have been printed in simplified versions.

"Those who are interested won’t miss opportunities just because they can't read traditional characters," says Li Xinkui.

However, Professor Huang Peirong from National Taiwan University believes that simplified versions of ancient texts cannot fully replace traditional literature.

This is because ancient poetry and literature often contain many phono-semantic borrowings, such as using "傑" (jié) as "杰" (also jié) and "適" (shì) as "适" (pronounced kuò). Are they truly synonymous, or is there an alternative borrowing? Can simplified versions fully interpret these meanings, or do they just add to the confusion?

After the opening up of mainland China, existing language issues became more pronounced.

Influenced by exchanges with Taiwan and Hong Kong, traditional characters have seen a resurgence in major cities on the mainland. Professor Yao Rongsong mentions an article by a mainland scholar noting that the phenomenon of "misusing" traditional characters is now visible nationwide.

Young people prefer to write traditional characters in formal settings, such as on blackboard titles, promotional slogans, notices, and posters, believing that traditional characters are more formal than simplified ones. This trend runs counter to the standardization of Chinese characters.

Piece of oracle bone engraved with early Chinese writing, Shang dynasty

Writing Traditional Characters as a Show of Style

An article in mainland China's "Legal System Daily" noted that a business card printing company receives an average of three thousand orders daily, with over half requesting traditional characters.

Another article mentioned that there are more traditional character plaques written by party and national leaders, as well as calligraphers. Even street vendors, including advertisements for "skin creams" aimed at local customers, use traditional characters to attract customers.

Li Xinkui pointed out that there is indeed a "resurgence of traditional characters" in major southern cities, but "it is mostly limited to a few institutions that have close ties with Taiwan and Hong Kong, or it is a deliberate attempt by the public to show off their elegance, making it fashionable to write in traditional characters."

Why do people feel the need to show off their style? Gong Pengcheng remarked that this phenomenon is worth the CCP's consideration.

He believes that the ability to use language aligns with cultural levels. Generally educated people can use commonly used characters; those with higher education can use less common characters; and those even better educated can use rare characters.

However, "this does not mean that those who write difficult or rare characters intend to separate themselves from the masses and curse those difficult characters as deserving to be simplified."

Thus, "as long as one considers themselves cultured, they will want to write traditional characters. As a society gradually develops and cultural standards rise, the frequency of traditional characters will naturally increase. This is the social nature of culture and the true trend of the development of writing," said Gong Pengcheng.

In recent years, the mainland government has recognized issues such as the arbitrary creation of characters like 迠 (jiàn), 拨 (bō), and 歺 (cān), as well as common mistakes such as confusing 復 (fù) with 複 (fù), 發 (fā) with 髮 (fà), and 鍾 (zhōng) with 鐘 (zhōng). The main focus of the mainland's "Language Committee" in recent years has been to regulate civilian usage of characters.

However, regarding the "resurgence of traditional characters" and the coexistence of traditional and simplified characters, the CCP's attitude has been very cautious, even intentionally restrained as traditional characters gradually gain popularity among the public.

During the Asian Games two years ago, over twenty thousand traditional character signs and advertisements were corrected by the Beijing municipal government. In July of last year, the overseas edition of the "People's Daily," originally printed in traditional characters to cater to overseas readers, switched back to simplified characters.

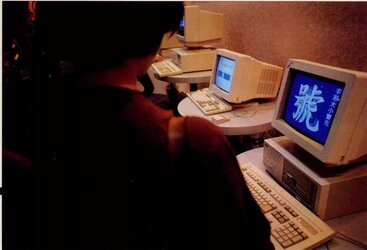

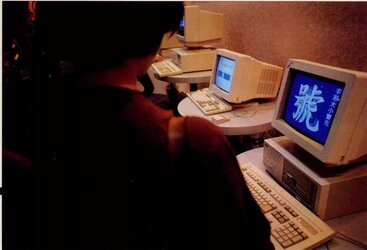

From oracle bone script to computer characters, Chinese writing has undergone many changes. Is the shift from complexity to simplicity an historical inevitability? This question is facing scrutiny today.

If You Don’t Do It Today, It Will Be Too Late Tomorrow!

Why is the CCP so adamant? Associate Professor Chou Chih-wen from Tamkang University points out that the CCP inherits the anti-traditional spirit from the May Fourth Movement, coupled with the Communists' indifference to culture and their use of culture as a political tool. This results in a significant divergence in how mainland leaders interpret language issues compared to Taiwan.

Taking a hardline approach, the CCP even treats the use of prescribed characters as an uncompromising policy goal. Liu Bin, the head of the Language Committee in mainland China, stated that language and writing are symbols of national sovereignty, and the direction of promoting simplified characters must not waver; otherwise, it would cause "incalculable losses to the socialist cause."

From the perspective of Taiwanese scholars, considering the inheritance of traditional culture and cross-strait communication, the issue of simplified characters on the mainland is not only necessary to address but also a matter of "if it’s not done today, it will be too late tomorrow."

Huang Peirong noted that today, intellectuals over forty on the mainland might still know traditional characters, but once these individuals pass away, discussing the essence of traditional culture or the integration of writing across the Taiwan Strait will be no easy task.

Out of a shared concern for Chinese cultural issues, scholars from both sides have held three meetings in mainland China since the opening of family visits to discuss the integration of writing. In Taiwan, recognizing the urgency of the Chinese language issue, the government has allocated funding to research topics like character usage across the strait and to establish Chinese computer standard exchange codes.

Is Communication Across the Strait Based on Writing?

The efforts on both sides are not without overlap. Led by Yuan Xiaoyuan, the president of the "Beijing International Chinese Character Research Association," some mainland scholars have proposed the idea of "recognizing traditional characters and writing simplified ones," hoping that at least everyone can come closer to traditional Chinese culture through their knowledge of traditional characters.

This proposal has also received responses from some Taiwanese scholars. Zheng Zhaoming believes that perhaps characters could be printed in traditional form and written in simplified form to resolve the dispute over character forms.

Many Taiwanese scholars feel that, realistically, achieving "recognizing traditional characters and writing simplified ones" would be a significant advancement for the mainland. Under the influence of scholars like Yuan Xiaoyuan, some key elementary schools in Beijing have even experimented with teaching traditional characters.

As cross-strait exchanges become increasingly close, more printing houses in the mainland are producing traditional character publications at the request of Taiwanese publishers, which all contributes to the education of traditional characters.

In Taiwan, the more pressing issue is that, in response to the increase in mainland printed materials, private typists urgently need to address courses on character correspondence between simplified and traditional forms. Overseas Chinese teachers also urgently require teaching materials that compare traditional and simplified characters.

Currently, there are many privately compiled comparison charts appearing in the printing industry, and software for character correspondence is publicly available. However, the standards for traditional and simplified characters in the market vary greatly, making usage very inconvenient, which necessitates unification.

It should be noted that learning simplified characters in the private sector does not indicate weakness towards the other side, nor does it mean "submitting" to reality; rather, if writing is a tool for communicating ideas, both sides should re-examine each other's writing. After understanding, interaction and influence can be discussed. From this perspective, writing truly is a starting point.

By Ma Zongtian

Simplified Chinese Characters with Traditional corrections

Due to the differences in written characters between the two sides (Taiwan and Mainland China), people visiting relatives in Mainland China might encounter the following confusion:

A flour shop (面粉店) – does it sell flour (麵粉), or is this a cosmetics store (面粉 can also refer to face powder)? "午會" – does this refer to a dance party (舞會), or a meeting held at noon (中午開會)? Which "丁" is it – is it "叮" (to ring), "丁" (a small object or person), "釘" (nail), or "盯" (to stare)? Which "采" is it – is it "採" (to pick), "踩" (to step on), "睬" (to pay attention to), "彩" (color), or "綵" (colored silk)?

"Ha! Teacher, you wrote the wrong character."

In December of last year, several children from mainland China visiting Taiwan were surprised to see "大庆油田" (Daqing Oilfield) written in large characters on the blackboard during their visit to a junior high school in Taipei, experiencing local classes.

“It has one more dot in it,” said one enthusiastic child. Little did she know that the teacher had originally intended not to write in simplified characters during class, and the extra dots in “庆” (qìng, celebrate) were deliberately included for their benefit, yet it still left the child disappointed.

The phenomenon of different written characters across the Taiwan Strait quietly occurs in our daily lives.

In April of this year, the Secretary-General of the Straits Exchange Foundation, Qiu Jinyi, traveled to the mainland to discuss matters regarding registered mail and document verification, negotiating with the mainland's Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits. They agreed that to "respect the language habits of both sides," documents would be signed in both simplified and traditional characters.

Since the opening up of cross-strait exchanges, many people have received letters from relatives and friends on the mainland entirely written in simplified characters, occasionally expressing their confusion about how to read them.

As exchanges between the two sides increase and more mainland publications circulate in Taiwan, many people often feel that mainland simplified books are like 'incomprehensible texts' that are difficult to understand.

Calligraphy art best showcases the distinct textures and complete symmetry of traditional characters. But is understanding traditional characters merely the privilege of calligraphers?

Half a Family, Instant Noodles?!

For the people visiting family in mainland China, the first thing that greets them upon passing through customs is the sight of Simplified Chinese characters everywhere. For those coming from Taiwan, although these Simplified characters and their usages are common, there is always a sense of entering a different environment.

For example: 搞活經濟 (revitalize the economy), 抓好物價 (stabilize prices), 通過函調 (conduct external inquiries via correspondence), 半邊家庭 (single-parent family), 超常兒童 (gifted children), 立交橋 (interchange), 方便麵 (instant noodles), and so on...

Lin Xinzhang, a former famous baseball coach in Taiwan, is now training baseball teams in the mainland. In the Taiwanese baseball community, he is often referred to as "Coach Xin" (信将), but now he is called "Coach Lin" (林指)

When friends from Taiwan visit him in the mainland and sit in the baseball stadium, listening to players from all around shout things like “来一棒” (let’s get a hit), “本壘跑” (home run), “好打好投” (good hitting and good pitching), they often find themselves “hearing but not understanding.”

There are even more characters that are hard to understand. For example, the character "干 (gān)" in mainland China can mean "to do," but it can also mean "干 (gān)" (dry) or "淦 (gàn)" (to be annoyed). "卜" (bǔ) can refer to "divination" (占卜, zhānbǔ) or "radish" (萝卜, luóbo); Is "麵粉" (miànfěn) for selling cosmetics or for opening a noodle shop? Is 开午会 (kāi wǔ huì) mean holding a meeting at noon or dancing?

Some describe the experience of reading simplified Chinese characters in the mainland as akin to being in the mainland itself: 亲 (qīn, meaning relation) without "见" (jiàn, meaning "to see") becomes a relationship without the act of seeing, 爱 (ài, love) without "心" (xīn, heart) lacks emotional depth, 产 (chǎn, to produce) that does not give birth, and the restroom "开关" (kāiguān, switch) that has no door.

Is '明天午會' (tomorrow's noon meeting) about a dance party? Or is it a meeting at noon tomorrow? The visitors from Taiwan can only ask their hometown folks.

Chinese Characters as Sacrificial Lambs

Such criticism is certainly sharp, but since the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) implemented language reform thirty-seven years ago, the use of simplified characters in mainland China has reached a point that necessitates re-examination.

In April of the year before last, Liu Bin, the director of the mainland's "National Language and Writing Work Committee," pointed out that the prominent language issues currently faced in mainland China are the rampant creation of characters and words, the deliberate use of traditional characters, and a significant number of misspellings.

The phenomenon of creating and using characters arbitrarily has a long history. Gong Pengcheng, director of the Cultural Education Department of the Mainland Affairs Council, believes that when the CCP initially promoted language reform, it did not consider the systematization and rationality of Chinese characters, which has led to the current root of the arbitrary creation of characters in society.

The CCP began promoting simplified characters in 1956. At that time, the proposed "Chinese Character Simplification Plan" listed more than two thousand simplified characters, which are now the standard for simplified characters in mainland China.

Mao Zedong once said: "Writing must be reformed; it should move towards a common phonetic direction of world writing." He believed that simplification was an inevitable historical path, aimed at preparing for the phoneticization of Chinese characters. This is related to the environment at the beginning of the Republic of China.

From the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic, from the Opium War to the eight-year Anti-Japanese War, our country experienced many setbacks under the invasion of foreign powers, leading to a weakened national strength and worsened living conditions.

Intellectuals seeking to strengthen the nation were very concerned, with some attributing blame to Chinese culture for being inferior, subsequently determining that the square-shaped Chinese characters could not compete with the phonetic letters of Western writing.

The significant rise in illiteracy was also attributed to the incomprehensibility of Chinese characters, hence the loud calls for language reform. The intellectuals of the May Fourth Movement, such as Qian Xuantong, Lu Xun, and Hu Shi, were all advocates for simplified characters.

Looking at the various street signs in the alleys of Guangzhou's bustling area, visitors from Taiwan only feel that 'many of the characters are written incorrectly.'

Simplified Characters are like the Red Guards!

Language and writing are tools for communication among people. When they develop over time, it is necessary to establish appropriate norms and reviews under reasonable circumstances. However, it is indeed rare in history for a regime, like the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), to concentrate a large number of intellectuals just a few years after seizing power to fully promote a policy of Chinese character simplification.

How significant is the impact of simplified characters? Professor Huang Yongwu from Taipei Municipal Teachers College once described simplified characters as "the Red Guards," referring to the harm they pose to Chinese culture.

He believes that simplified characters undermine the inherent structural system of Chinese writing and lack superior academic conditions. As a result, future generations may be unable to understand Chinese characters and become estranged from traditional culture, with the damage being comparable to that caused by the Red Guards.

For example, he points out that the character "葉" (yè, leaf) contains the "艸" (cǎo, grass) radical, which indicates it belongs to the plant category and is immediately recognizable.

Meanwhile, characters sharing the same phonetic component, such as "成薄片狀" (chéng bópiàn zhuàng, "to become thin slices"), have phonetic elements that convey meaning.

Other characters that share the same phonetic component include "諜" (dié, spy), "碟" (dié, dish), "蝶" (dié, butterfly), and "喋" (dié, chatter), where the left side represents the category of the object and the right side conveys the sound and meaning.

Unfortunately, writing "葉" as "叶" not only disrupts the radical but also loses the semantic system of "薄片狀草木" (bópiàn zhuàng cǎomù, "thin slice plants") within the character system.

Similarly, when "髮" (fà, hair) is simplified to "发", it raises ambiguity: does "秀發" (xiùfà, beautiful hair) refer to beautiful hair or smart hair? What about "叶韻" (yè yùn, rhyme of leaves) — does it refer to "ancient poetry rhyme" or "the entering tone of leaves"?

Research by Professor Huang Peirong from National Taiwan University also points out issues with mainland China's language reform, such as confused characters — like "嘆" (tàn, sigh), "漢" (hàn, Han), "勸" (quàn, persuade), "觀" (guān, observe), and "戲" (xì, play) all belonging to the "又" (yòu) radical — and destruction of structure — for instance, "華" (huá, splendid) simplified to "华," "書" (shū, book) to "书," "堯" (yáo, Yao) to "尧," and loss of root words — like "構" (gòu, structure) simplified to "构."

These issues complicate learning and hinder contemporary understanding of ancient texts, negatively impacting cultural transmission.

Carefully examining these signs, the main problems of word usage in mainland society—such as the arbitrary creation of new characters, the use of simplified characters, and the frequent misspellings—are all evident.

Teaching Efficiency is Unrelated to Complexity

However, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) argues that there are many illiterate individuals in mainland China, and it is "impossible to demand that everyone understand the profound traditional characters."

Professor Li Xinkui from Sun Yat-sen University in Guangdong believes that cultural progress varies; common villagers do not need to know so many difficult or obscure characters. Practical characters for daily life are sufficient. When they have enough knowledge or a desire to learn and truly wish to understand the past and present, it is not too late to learn traditional characters.

Professor Li points out the main motivation behind the CCP's implementation of the simplification scheme: that simplified characters facilitate the popularization of education. However, to this day, many harsh realities have dealt a blow to the simplification policy.

"Taiwan does not follow the path of simplification, and its literacy rate exceeds ninety-five percent; after over thirty years of promoting simplified characters in mainland China, it appears that illiteracy has not decreased," says Huang Peirong.

Moreover, in terms of teaching efficiency, simplified characters may not be superior to traditional characters.

Research by Professor Zheng Zhaoming from National Taiwan University indicates that learning characters involves "the differentiation of words" and "the identification of meanings," both of which are unrelated to the complexity of strokes.

Characters with complex and simple strokes may be similarly difficult to distinguish, such as "傅" (fù, to teach) and "傳" (chuán, to transmit), or "已" (yǐ, already) and "己" (jǐ, self). Conversely, they may be easily distinguished due to their differences, like "補" (bǔ, to supplement) and "馳" (chí, to gallop), or "田" (tián, field) and "戶" (hù, door).

A business card printed by a shop in Guangzhou is entirely in traditional characters. Is it just a show of style?

The Rise of the 'New Cultural Class'?

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) believes that only those studying literature and history or practicing calligraphy need to learn traditional characters, a view that is open to debate. Huang Peirong points out that breaking down class barriers and allowing the proletariat to rise was originally a hallmark of the CCP regime. Today, being able to read traditional characters has become a new kind of "cultural class."

Another reason the mainland does not think simplified characters hinder cultural transmission is that for over thirty years, many ancient poetry and literature publications, such as "Dream of the Red Chamber," "Commentaries on Records of the Grand Historian," and "Three Hundred Tang Poems," have been printed in simplified versions.

"Those who are interested won’t miss opportunities just because they can't read traditional characters," says Li Xinkui.

However, Professor Huang Peirong from National Taiwan University believes that simplified versions of ancient texts cannot fully replace traditional literature.

This is because ancient poetry and literature often contain many phono-semantic borrowings, such as using "傑" (jié) as "杰" (also jié) and "適" (shì) as "适" (pronounced kuò). Are they truly synonymous, or is there an alternative borrowing? Can simplified versions fully interpret these meanings, or do they just add to the confusion?

After the opening up of mainland China, existing language issues became more pronounced.

Influenced by exchanges with Taiwan and Hong Kong, traditional characters have seen a resurgence in major cities on the mainland. Professor Yao Rongsong mentions an article by a mainland scholar noting that the phenomenon of "misusing" traditional characters is now visible nationwide.

Young people prefer to write traditional characters in formal settings, such as on blackboard titles, promotional slogans, notices, and posters, believing that traditional characters are more formal than simplified ones. This trend runs counter to the standardization of Chinese characters.

Piece of oracle bone engraved with early Chinese writing, Shang dynasty

Writing Traditional Characters as a Show of Style

An article in mainland China's "Legal System Daily" noted that a business card printing company receives an average of three thousand orders daily, with over half requesting traditional characters.

Another article mentioned that there are more traditional character plaques written by party and national leaders, as well as calligraphers. Even street vendors, including advertisements for "skin creams" aimed at local customers, use traditional characters to attract customers.

Li Xinkui pointed out that there is indeed a "resurgence of traditional characters" in major southern cities, but "it is mostly limited to a few institutions that have close ties with Taiwan and Hong Kong, or it is a deliberate attempt by the public to show off their elegance, making it fashionable to write in traditional characters."

Why do people feel the need to show off their style? Gong Pengcheng remarked that this phenomenon is worth the CCP's consideration.

He believes that the ability to use language aligns with cultural levels. Generally educated people can use commonly used characters; those with higher education can use less common characters; and those even better educated can use rare characters.

However, "this does not mean that those who write difficult or rare characters intend to separate themselves from the masses and curse those difficult characters as deserving to be simplified."

Thus, "as long as one considers themselves cultured, they will want to write traditional characters. As a society gradually develops and cultural standards rise, the frequency of traditional characters will naturally increase. This is the social nature of culture and the true trend of the development of writing," said Gong Pengcheng.

In recent years, the mainland government has recognized issues such as the arbitrary creation of characters like 迠 (jiàn), 拨 (bō), and 歺 (cān), as well as common mistakes such as confusing 復 (fù) with 複 (fù), 發 (fā) with 髮 (fà), and 鍾 (zhōng) with 鐘 (zhōng). The main focus of the mainland's "Language Committee" in recent years has been to regulate civilian usage of characters.

However, regarding the "resurgence of traditional characters" and the coexistence of traditional and simplified characters, the CCP's attitude has been very cautious, even intentionally restrained as traditional characters gradually gain popularity among the public.

During the Asian Games two years ago, over twenty thousand traditional character signs and advertisements were corrected by the Beijing municipal government. In July of last year, the overseas edition of the "People's Daily," originally printed in traditional characters to cater to overseas readers, switched back to simplified characters.

From oracle bone script to computer characters, Chinese writing has undergone many changes. Is the shift from complexity to simplicity an historical inevitability? This question is facing scrutiny today.

If You Don’t Do It Today, It Will Be Too Late Tomorrow!

Why is the CCP so adamant? Associate Professor Chou Chih-wen from Tamkang University points out that the CCP inherits the anti-traditional spirit from the May Fourth Movement, coupled with the Communists' indifference to culture and their use of culture as a political tool. This results in a significant divergence in how mainland leaders interpret language issues compared to Taiwan.

Taking a hardline approach, the CCP even treats the use of prescribed characters as an uncompromising policy goal. Liu Bin, the head of the Language Committee in mainland China, stated that language and writing are symbols of national sovereignty, and the direction of promoting simplified characters must not waver; otherwise, it would cause "incalculable losses to the socialist cause."

From the perspective of Taiwanese scholars, considering the inheritance of traditional culture and cross-strait communication, the issue of simplified characters on the mainland is not only necessary to address but also a matter of "if it’s not done today, it will be too late tomorrow."

Huang Peirong noted that today, intellectuals over forty on the mainland might still know traditional characters, but once these individuals pass away, discussing the essence of traditional culture or the integration of writing across the Taiwan Strait will be no easy task.

Out of a shared concern for Chinese cultural issues, scholars from both sides have held three meetings in mainland China since the opening of family visits to discuss the integration of writing. In Taiwan, recognizing the urgency of the Chinese language issue, the government has allocated funding to research topics like character usage across the strait and to establish Chinese computer standard exchange codes.

Is Communication Across the Strait Based on Writing?

The efforts on both sides are not without overlap. Led by Yuan Xiaoyuan, the president of the "Beijing International Chinese Character Research Association," some mainland scholars have proposed the idea of "recognizing traditional characters and writing simplified ones," hoping that at least everyone can come closer to traditional Chinese culture through their knowledge of traditional characters.

This proposal has also received responses from some Taiwanese scholars. Zheng Zhaoming believes that perhaps characters could be printed in traditional form and written in simplified form to resolve the dispute over character forms.

Many Taiwanese scholars feel that, realistically, achieving "recognizing traditional characters and writing simplified ones" would be a significant advancement for the mainland. Under the influence of scholars like Yuan Xiaoyuan, some key elementary schools in Beijing have even experimented with teaching traditional characters.

As cross-strait exchanges become increasingly close, more printing houses in the mainland are producing traditional character publications at the request of Taiwanese publishers, which all contributes to the education of traditional characters.

In Taiwan, the more pressing issue is that, in response to the increase in mainland printed materials, private typists urgently need to address courses on character correspondence between simplified and traditional forms. Overseas Chinese teachers also urgently require teaching materials that compare traditional and simplified characters.

Currently, there are many privately compiled comparison charts appearing in the printing industry, and software for character correspondence is publicly available. However, the standards for traditional and simplified characters in the market vary greatly, making usage very inconvenient, which necessitates unification.

It should be noted that learning simplified characters in the private sector does not indicate weakness towards the other side, nor does it mean "submitting" to reality; rather, if writing is a tool for communicating ideas, both sides should re-examine each other's writing. After understanding, interaction and influence can be discussed. From this perspective, writing truly is a starting point.