- Joined

- Aug 8, 2021

The subject of religious syncretism in Peru, whether it exists (there, or anywhere), and it's possible contours came up in another thread over in A&N, which reminded me of the wild world of syncretic religion among their northern neighbors, the Aztecs and Maya. Rather than derailing a news article thread, I decided I'd brain dump the examples I had in mind here, in case people want to contribute more and discuss anthropology/philosophy nerd stuff. While my examples are all Mesoamerican, because that's where my autism lies (and they are representative, not exhaustive, I could go on for dozens of pages about this subject), feel free to sperg on syncretism in other cultures, gentle readers! (There's got to be someone around here somewhere who's familiar with Santeria/Palo Mayombe/Voudoun and wants to let their inner autist run free at last...)

Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala (Present-Day Maya) -- Holy Week & Passion of Ma'Nawal JesuKristo

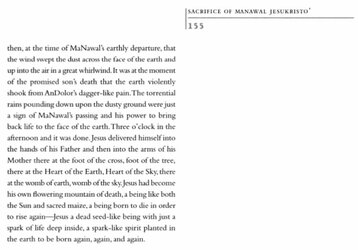

Going to start off with the tastiest example -- a retelling of the Passion of Jesus, by a Mayan cofradia religious society member in Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala. This was sourced from Chapter Nine in Rituals of Sacrifice: Walking the Face of the Earth on the Sacred Path of the Sun : a Journey Through the Tz'utujil Maya World of Santiago Atitlán, by Vincent Stanzione (2003). I no longer have this book in my personal library, but I was able to pull the pages I wanted from a Google Books preview session. (There are no free or """free""" copies reasonably available of this one, it's a bit too niche even for pirates I suppose.)

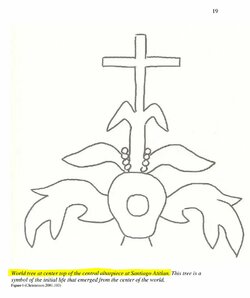

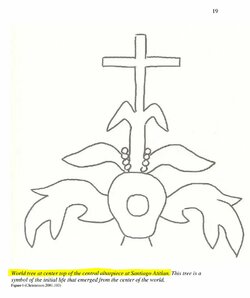

This story is a lively and complex example of hybridization between Catholicism and pre-Christian Mayan folk religion. In it, Jesus, called Ma'Nawal (Ma'Nawal -> Manuel -> Immanuel) JesuKristo, accompanied by his friend Ma'Ximon/Mam/San Pedro/Judas, and advised by his mentor Aklax/San Nicolas, has recently flipped over the tables in the temple. The K'ulutun winaq (malevolent earth/death priests and demigods)/Pharisees are pissed, and have decided it's time for him to die. From there, the story is a mix of familiar and very much so not, the bones of the New Testament story wrapped with a skin of Mayan characters and symbols, and containing a heart of pre-Conquest Mesoamerican religious thought. In its final scene, Ma'Nawal is crucified on a cross that is also the flowering World Tree of Mayan myth, which, watered with his blood, bursts into life, its roots tapping the waters of the underworld below and releasing the rainy season, the first expression of JesuKristo's new existence as a god of the rains and spring vegetation.

I've also included a few more extracts from Chapter 10, which gives some more information in general on Holy Week beliefs and practices among these Maya. Sorry for the missing photos, but Google didn't have permissions to show them in a preview.

Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala (Present-Day Maya) -- Ma'Ximon/Mam/Saint Nicholas

So who exactly was Ma'Ximon in the story above? A wonderfully weird character composed of an amalgamation of Mam, an earth deity and trickster (likely himself a modern evolution of the name still unknown "God L" of the Maya, who was probably their version of the better-documented Tezcatlipoca of the Aztecs, with some traits drawn from Chaac the rain god, called Tlaloc by the Aztecs), with, of all people, Saint Peter and sometimes Judas Iscariot as well. He's the special patron of Santiago Atitlan, and his religious society/cult (in the anthropological sense, not the creepy pseudoreligion way) is based in that town. His cofradia society maintains an official website up with information on him, including his origin myth, and even a virtual temple where you can worship and ask favors of the mercurial and sometimes generous god.

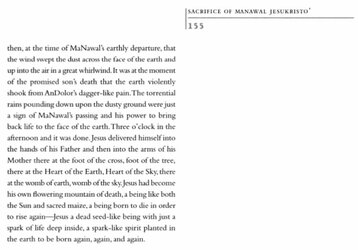

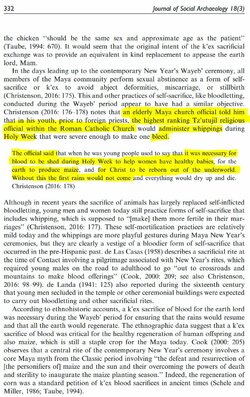

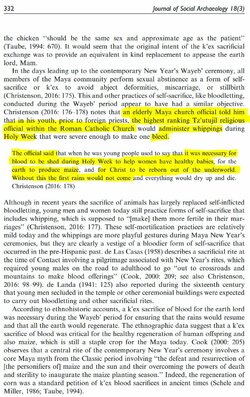

Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala (Present-Day Maya) -- Holy Week Blood Sacrifice

Short and sweet. A snippet from an interview with an elderly Mayan official of the Catholic Church, where he talks briefly about how when he was young, his superior used to conduct penitential whippings, hard enough to cause profuse bleeding, as a sacrifice to cause the rains to come and good harvests to follow, among other benefits... like helping Jesus to resurrect after the Crucifixion. This was sourced from It’s the journey not the destination: Maya New Year’s pilgrimage and self-sacrifice as regenerative power, by Eleanor Harrison-Buck. (Journal of Social Archaeology 2018, Vol. 18(3) 325–347) I've attached a copy of the article, and it can also be read HERE.

Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala (Present-Day Maya) -- Altarpiece of Santiago Atitlan, A Visual Synthesis of Mayan Folk Religion & Catholicism

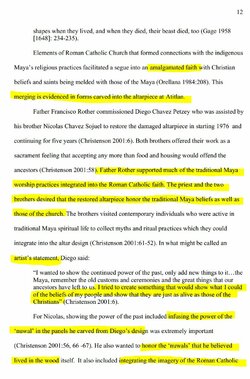

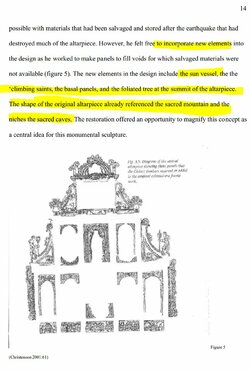

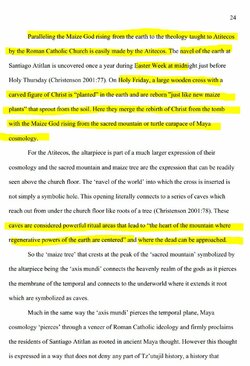

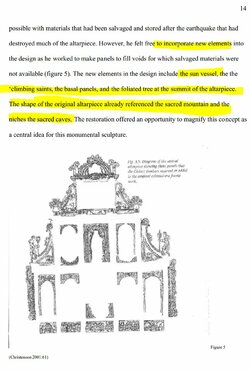

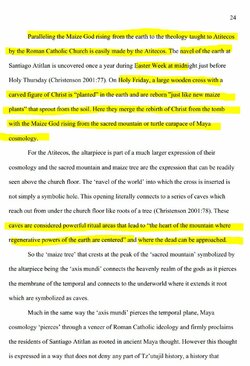

One more bit from Guatemala. There's an elaborate altarpiece in the colonial-era church there that's a deliberate mix of Catholic and indigenous Mayan religious symbols. About half of the material is original to the 1600s, and the rest was added during a massive restoration in the 1960s after the church was severely damaged and about half the altarpiece was destroyed. My source includes interviews with the two artists who designed and carried out the restoration, who aren't shy about their religious beliefs. The paper I pulled the below extracts from is The Altarpiece of Santiago Atitlan: The ‘Flowering Earth Mountain’, by Barbara E. Verchot, which can be read in full HERE. The paper itself is a condensed analysis of another book that is unfortunately a bitch to get a hold of -- that would be Art and Society in a Highland Maya Community The Altarpiece of Santiago Atitlán, by Allen J. Christenson (2001), and is a key reference for those studying syncretism in practice in Central America.

These pages I screencapped below document only a portion of the Mayan symbols mixed into the Catholic altarpiece, see the full paper if you want to check them all out. I picked these ones to give a reasonable taste of what's there, and also because some of them add even more information relating to the Mayan/Catholic hybrid Easter practices mentioned earlier.

Mexico City/Central Valley, Mexico (Early Colonial Aztecs) -- Saints, Indigenous Deities, & Folk Magic

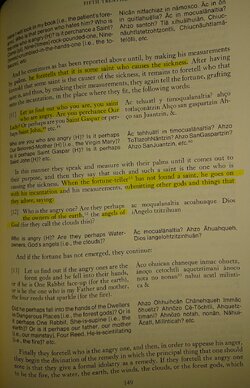

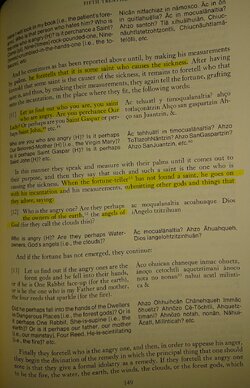

Moving time, place, and culture, this section shares an example of syncretization among the Aztecs during the early Colonial period (1525-1650), in Central Mexico. It's a prayer/magic spell performed by certain kinds of curandero folk healers/sorcerors, intended to divine the supernatural being who caused the illness the healer's patient has come to them for help with. This single prayer contains invocations of a mix of prehispanic and Catholic gods, saints, and other divine beings. Source is pages 149 and 150 of Ruiz de Alarcon's Treatise on the Heathen Superstitions That Today Live Among the Indians Native to This New Spain. 1629 (1987 paperback English imprint), an invaluable primary resource on folk magic and beliefs of this particular time and place. AFAIK there are no readily available electronic versions of this, so I've photographed the chosen example from my personal copy of this book. Sorry for the shit photos, I picked my cellphone for features other than its camera, but they're free to you, so you get what you pay for. Click to expand for better readability.

Merging pre-Christian indigenous beliefs with Spanish Catholicism was not something limited only to the Maya of present-day Guatemala, but is a practice with a 500 year track record across all of Central America and its native cultures.

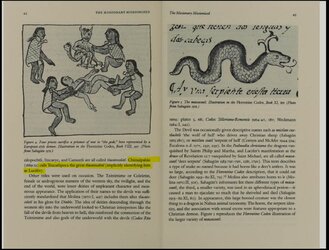

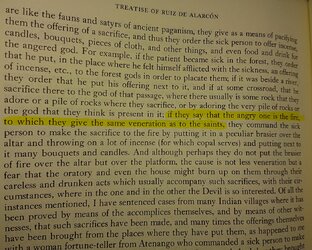

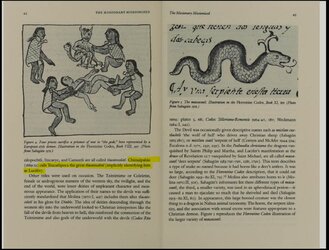

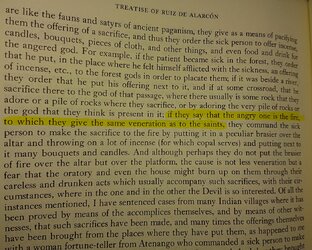

Mexico City/Central Valley, Mexico (Early Colonial Aztecs) -- What's In A Name, Witches, Devils, Gods, & Owl-Men

The last example of Mesoamerican/Catholic religious syncretism is pulled from Louise Burkhart's 1989 treatise, The slippery earth : Nahua-Christian moral dialogue in sixteenth-century Mexico. Fulltext is available for free at Archive.org if you log in and check it out. The entire book itself deals with syncretization among the Aztecs in the immediate post-Conquest period (1500s), but I've picked out just one example, as much of the rest of the book probably won't completely make sense if you're not already heavily familiar with the history and cultures discussed -- the author's mostly analyzing the two without actually reprinting the subjects discussed, expecting the reader to have their own reference materials at hand. This one, however, is a bit more self-contained, and lent itself to yanking and posting. It covers the problem of naming things, especially God, Mary, and Satan. God and Mary frequently recycled titles and names from some of the indigenous gods and goddesses, as they were licit figures of veneration, although this wasn't done without unease by some of the Catholic officials, concerned by the possibility of either merging pagan concepts into the local Catholic beliefs among the recently and incompletely converted Aztecs, or allowing an easy cover for continued worship of the native gods in a way that would make it harder to detect.

Satan, however, was a particular issue -- how to translate him to a worldview that is organized more along order/chaos lines, rather than good/evil, and that doesn't have any useful analogues to angels, fallen or not, or broadly powerful supernatural beings that are godlike, but not actually gods to worship? The Spanish friars, to get around this problem, had to resort to repurposing one of the only non-deity hostile underworld figures they could find in the mythology -- a type of shapeshifting death witch called the "human owl." However, it was a poor fit, as the character was a far cry from a fallen Seraph, resulting in a local conception of Lucifer that was more indigenous than orthodox Catholic under the surface.

Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala (Present-Day Maya) -- Holy Week & Passion of Ma'Nawal JesuKristo

Going to start off with the tastiest example -- a retelling of the Passion of Jesus, by a Mayan cofradia religious society member in Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala. This was sourced from Chapter Nine in Rituals of Sacrifice: Walking the Face of the Earth on the Sacred Path of the Sun : a Journey Through the Tz'utujil Maya World of Santiago Atitlán, by Vincent Stanzione (2003). I no longer have this book in my personal library, but I was able to pull the pages I wanted from a Google Books preview session. (There are no free or """free""" copies reasonably available of this one, it's a bit too niche even for pirates I suppose.)

This story is a lively and complex example of hybridization between Catholicism and pre-Christian Mayan folk religion. In it, Jesus, called Ma'Nawal (Ma'Nawal -> Manuel -> Immanuel) JesuKristo, accompanied by his friend Ma'Ximon/Mam/San Pedro/Judas, and advised by his mentor Aklax/San Nicolas, has recently flipped over the tables in the temple. The K'ulutun winaq (malevolent earth/death priests and demigods)/Pharisees are pissed, and have decided it's time for him to die. From there, the story is a mix of familiar and very much so not, the bones of the New Testament story wrapped with a skin of Mayan characters and symbols, and containing a heart of pre-Conquest Mesoamerican religious thought. In its final scene, Ma'Nawal is crucified on a cross that is also the flowering World Tree of Mayan myth, which, watered with his blood, bursts into life, its roots tapping the waters of the underworld below and releasing the rainy season, the first expression of JesuKristo's new existence as a god of the rains and spring vegetation.

I've also included a few more extracts from Chapter 10, which gives some more information in general on Holy Week beliefs and practices among these Maya. Sorry for the missing photos, but Google didn't have permissions to show them in a preview.

Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala (Present-Day Maya) -- Ma'Ximon/Mam/Saint Nicholas

So who exactly was Ma'Ximon in the story above? A wonderfully weird character composed of an amalgamation of Mam, an earth deity and trickster (likely himself a modern evolution of the name still unknown "God L" of the Maya, who was probably their version of the better-documented Tezcatlipoca of the Aztecs, with some traits drawn from Chaac the rain god, called Tlaloc by the Aztecs), with, of all people, Saint Peter and sometimes Judas Iscariot as well. He's the special patron of Santiago Atitlan, and his religious society/cult (in the anthropological sense, not the creepy pseudoreligion way) is based in that town. His cofradia society maintains an official website up with information on him, including his origin myth, and even a virtual temple where you can worship and ask favors of the mercurial and sometimes generous god.

Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala (Present-Day Maya) -- Holy Week Blood Sacrifice

Short and sweet. A snippet from an interview with an elderly Mayan official of the Catholic Church, where he talks briefly about how when he was young, his superior used to conduct penitential whippings, hard enough to cause profuse bleeding, as a sacrifice to cause the rains to come and good harvests to follow, among other benefits... like helping Jesus to resurrect after the Crucifixion. This was sourced from It’s the journey not the destination: Maya New Year’s pilgrimage and self-sacrifice as regenerative power, by Eleanor Harrison-Buck. (Journal of Social Archaeology 2018, Vol. 18(3) 325–347) I've attached a copy of the article, and it can also be read HERE.

Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala (Present-Day Maya) -- Altarpiece of Santiago Atitlan, A Visual Synthesis of Mayan Folk Religion & Catholicism

One more bit from Guatemala. There's an elaborate altarpiece in the colonial-era church there that's a deliberate mix of Catholic and indigenous Mayan religious symbols. About half of the material is original to the 1600s, and the rest was added during a massive restoration in the 1960s after the church was severely damaged and about half the altarpiece was destroyed. My source includes interviews with the two artists who designed and carried out the restoration, who aren't shy about their religious beliefs. The paper I pulled the below extracts from is The Altarpiece of Santiago Atitlan: The ‘Flowering Earth Mountain’, by Barbara E. Verchot, which can be read in full HERE. The paper itself is a condensed analysis of another book that is unfortunately a bitch to get a hold of -- that would be Art and Society in a Highland Maya Community The Altarpiece of Santiago Atitlán, by Allen J. Christenson (2001), and is a key reference for those studying syncretism in practice in Central America.

These pages I screencapped below document only a portion of the Mayan symbols mixed into the Catholic altarpiece, see the full paper if you want to check them all out. I picked these ones to give a reasonable taste of what's there, and also because some of them add even more information relating to the Mayan/Catholic hybrid Easter practices mentioned earlier.

Mexico City/Central Valley, Mexico (Early Colonial Aztecs) -- Saints, Indigenous Deities, & Folk Magic

Moving time, place, and culture, this section shares an example of syncretization among the Aztecs during the early Colonial period (1525-1650), in Central Mexico. It's a prayer/magic spell performed by certain kinds of curandero folk healers/sorcerors, intended to divine the supernatural being who caused the illness the healer's patient has come to them for help with. This single prayer contains invocations of a mix of prehispanic and Catholic gods, saints, and other divine beings. Source is pages 149 and 150 of Ruiz de Alarcon's Treatise on the Heathen Superstitions That Today Live Among the Indians Native to This New Spain. 1629 (1987 paperback English imprint), an invaluable primary resource on folk magic and beliefs of this particular time and place. AFAIK there are no readily available electronic versions of this, so I've photographed the chosen example from my personal copy of this book. Sorry for the shit photos, I picked my cellphone for features other than its camera, but they're free to you, so you get what you pay for. Click to expand for better readability.

Merging pre-Christian indigenous beliefs with Spanish Catholicism was not something limited only to the Maya of present-day Guatemala, but is a practice with a 500 year track record across all of Central America and its native cultures.

Mexico City/Central Valley, Mexico (Early Colonial Aztecs) -- What's In A Name, Witches, Devils, Gods, & Owl-Men

The last example of Mesoamerican/Catholic religious syncretism is pulled from Louise Burkhart's 1989 treatise, The slippery earth : Nahua-Christian moral dialogue in sixteenth-century Mexico. Fulltext is available for free at Archive.org if you log in and check it out. The entire book itself deals with syncretization among the Aztecs in the immediate post-Conquest period (1500s), but I've picked out just one example, as much of the rest of the book probably won't completely make sense if you're not already heavily familiar with the history and cultures discussed -- the author's mostly analyzing the two without actually reprinting the subjects discussed, expecting the reader to have their own reference materials at hand. This one, however, is a bit more self-contained, and lent itself to yanking and posting. It covers the problem of naming things, especially God, Mary, and Satan. God and Mary frequently recycled titles and names from some of the indigenous gods and goddesses, as they were licit figures of veneration, although this wasn't done without unease by some of the Catholic officials, concerned by the possibility of either merging pagan concepts into the local Catholic beliefs among the recently and incompletely converted Aztecs, or allowing an easy cover for continued worship of the native gods in a way that would make it harder to detect.

Satan, however, was a particular issue -- how to translate him to a worldview that is organized more along order/chaos lines, rather than good/evil, and that doesn't have any useful analogues to angels, fallen or not, or broadly powerful supernatural beings that are godlike, but not actually gods to worship? The Spanish friars, to get around this problem, had to resort to repurposing one of the only non-deity hostile underworld figures they could find in the mythology -- a type of shapeshifting death witch called the "human owl." However, it was a poor fit, as the character was a far cry from a fallen Seraph, resulting in a local conception of Lucifer that was more indigenous than orthodox Catholic under the surface.