Low water levels outside the Miraflores locks of the Panama Canal near Panama City, Nov. 3, 2023. The Panama Canal is so shallow from climate change that quotas are being imposed on how many ships can use the artery, a decision destined to snarl trade in energy, consumer goods and food as carriers are forced to sail thousands of extra miles to make deliveries. (Walter Hurtado / Bloomberg)

The vestiges of an ancient forest tell the story of just how bad things are at the drought-stricken Panama Canal.

A few hundred feet from the massive tankers hauling goods across the globe, gaunt tree stumps rise above the waterline. They’re all that remains of a woodland flooded more than a century ago to create the canal. It’s not unusual to see them at the height of the dry season — but now, in the immediate aftermath of what’s usually the rainy period, they should be fully submerged.

They’re a visible reminder of how parched conditions have crippled a waterway that handles $270 billion a year in global trade. And there are no easy solutions. The Panama Canal Authority is weighing potential fixes that include an artificial lake to pump water into the canal and cloud seeding to boost rainfall, but both options would take years to implement, if they’re even feasible.

With water levels languishing at 6 feet below normal, the canal authority capped the number of vessels that can cross. The limits imposed late last year were the strictest since 1989, when the conduit was shut as the U.S. invaded Panama to extract its de facto ruler, Manuel Noriega. Some shippers are paying millions of dollars to jump the growing queue, while others are taking longer, costlier routes around Africa or South America.

The constraints have since eased slightly due to a rainier-than-expected November, but at 24 ships a day, the maximum is still well below the pre-drought daily capacity of about 38. As the dry season takes hold, the bottleneck is poised to worsen again.

“As a canal, as a country, we need to take some measures because it isn’t acceptable,” Erick Córdoba, the manager of the water division at the canal authority, said in an interview. “We need to calibrate the system again.”

The canal’s travails reflect how climate change is altering global trade flows. Drought created chokepoints last year on the Mississippi River and the Rhine in Europe. In the UK, rising sea levels are elevating the risk of flooding along the Thames. Melting ice is creating new shipping routes in the Arctic.

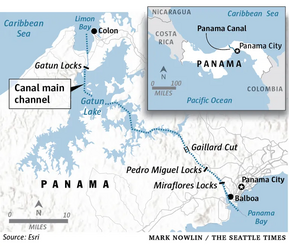

Under normal circumstances, the Panama Canal handles about 3% of global maritime trade volumes and 46% of containers moving from Northeast Asia to the U.S. East Coast. The channel is Panama’s biggest source of revenue, bringing in $4.3 billion in 2022.

To allow for 24 vessels a day through the dry season, the canal will release water from Lake Alajuela, a secondary reservoir. If the rains begin to pick up in May, the canal might be able to start increasing traffic, according to Córdoba.

But those are short-term fixes. In the long term, the primary solution to chronic water shortages will be to dam up the Indio River and then drill a tunnel through a mountain to pipe fresh water 5 miles into Lake Gatún, the canal’s main reservoir.

The project, along with additional conservation measures, will cost about $2 billion, Córdoba estimates. He says it will take at least six years to dam up and fill the site. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is conducting a feasibility study.

The Indio River reservoir would increase vessel traffic by 11 to 15 a day, enough to keep Panama’s top moneymaker working at capacity while guaranteeing fresh water for Panama City, where developers have erected a mini-Miami of gleaming skyscrapers over the past two decades. The country will need to dam even more rivers to guarantee water through the end of the century.

Moving the proposal forward won’t be easy. It will need congressional approval, and the thousands of farmers and ranchers whose lands would be flooded for the reservoir are already organizing to oppose it.

It’s not the first time Panamanians are banding together to push back against a major infrastructure initiative. Last year, protesters regularly blocked roads after the government rushed to keep First Quantum Minerals Ltd.’s $10 billion copper mine operating. Authorities have since said that they will shut the mine, a project many view as an ecological disaster.

Elizabeth Delgado, 38, lives in the last house along the road to the Indio River. It’s one of the first that will get flooded if the reservoir is built. During major storms, the Indio rises enough to get within a few meters of her unpainted wooden home, where her family lives off of the rice, plantains and cassava she grows. She has no intention of moving.

“How are we supposed to survive someplace else where we won’t know what to do?” Delgado said. “They’ve told us that we’re going to have to leave, but we’re going to stick with our land.”

Another potential fix is decidedly more experimental. In November, a small plane operated by North Dakota-based Weather Modification Inc. arrived in Panama to test cloud seeding, the process of implanting large salt particles into clouds to boost the condensation that creates rain.

But cloud seeding has mostly been deployed successfully in dry climates, not in tropical countries like Panama.

Some shippers have expressed frustration that the canal authority isn’t moving faster to address low water levels.

“No significant infrastructure projects have gone ahead in Panama to increase the fresh water supply,” Jeremy Nixon, chief executive officer of Japanese container transportation company Ocean Network Express Holdings, or ONE, wrote in a letter to Panamanian President Laurentino Cortizo Cohen that was seen by Bloomberg. “We sincerely hope that as ONE, and on behalf of our customers, that some urgent action can now be taken.”

Panama’s presidential palace didn’t respond to a request for comment on the letter.

Article Link

Archive