- Joined

- Feb 16, 2022

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

say what u want to say

- Thread starter Null

- Start date

- Joined

- Feb 24, 2019

Been looking for a home for this book I found:

- Joined

- Sep 26, 2019

Dunderpuff

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Feb 8, 2018

@Null your uncompromising stance on resisting things like this gives me hope

Buster Hymen

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- May 16, 2021

This is most definitely not what's up tubez. The death of the last bastion of freedom and funny Real Tawk. From a lurker thanks for all the good times and funny posts. R.I.P. kiwifarms

- Joined

- Nov 27, 2018

Meow mrewo maow meow mreow MEOW MEOW MEOW maow mreow maw raaaaeow meow

- Joined

- Jan 14, 2020

- Joined

- Jul 30, 2015

Kiwi Farms will stop trending on twatter and everything will go back to normal eventually

Mischief Committee

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Dec 23, 2017

To the congressional commission that has subpoenaed me today at a future date and will be reading this and many other posts aloud: Hi fwens

- Joined

- Feb 5, 2019

doomposting is cringe

- Joined

- Jan 13, 2019

- Joined

- Sep 30, 2019

I just wanted to have fun without politics.

Didn't completely get that here, but it came closer than most other places.

Feels bad man. Hope things turn out well.

Didn't completely get that here, but it came closer than most other places.

Feels bad man. Hope things turn out well.

- Joined

- Nov 6, 2021

I've been tirelessly working on designing the kiwigglers key chain designs. If this site goes down I don't think I'll continue with the business proposition for null.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Nov 26, 2019

- Joined

- Oct 11, 2020

Flea Man Marbles

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- May 20, 2019

I value kiwifarms as a sort of news source/social feedback chamber and a community moreso than, say, the laughing at lol-cows part. Kiwifarms may take tranny lives but for others, it's a lifesaver.

- Joined

- Oct 13, 2020

Fuck the UN. And fuck the WEF. And fuck the WHO. And fuck the Antichrist. And fuck communism.

Celestia's Little Helper

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Mar 11, 2020

I will continue to use the site as if nothing it wrong, just how I’ve always done in times of hardship.

- Joined

- Feb 5, 2019

Sleazy Car Salesman

Believe me when I say that I will take your money

True & Honest Fan

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- May 27, 2021

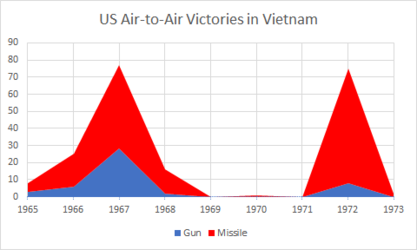

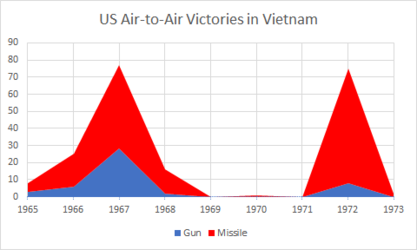

A number of reasons; the key one being that the US Navy trained its pilots to use missiles correctly, and was able to maintain and care for them better. A secondary issue, particularly for the AIM-9, was that the USN developed more effective missiles.

As a result, the USN achieved significantly better “kill ratios” in air-to-air combat: in 1972, over “Linebacker I” and “Linebacker II”, the USAF lost twenty-four aircraft to the NVAF while scoring 48 kills, for a 2:1 ratio (despite flying F-4D and F-4E Phantoms with either a centreline gunpod, or an internal M61 Vulcan). The USN shot down twenty-four MiGs for four air-to-air losses, for a 6:1 kill ratio despite using missiles alone.

Worse was the outcome of engagements: beyond the kill ratios, the NVAF engaged USN aircraft 26 times, while they clashed with the USAF on eighty-two occasions. So, on average, fighting the USN meant losing an aircraft for a one-in-seven chance of scoring a kill: as a result, the NVAF seemed to prioritise the USAF as targets despite their Phantoms having guns.

There were reasons behind all these factors: geography, politics, training structures and requirements, airbase layouts… but the upshot was that in the short term, the USAF found it easier to blame their “limited success” (a 2:1 kill ratio would usually be considered pretty good, but…) on being forced to fly a Navy aircraft that didn’t have the vital cannon (only seven of the 48 USAF kills were actually with cannon) rather than confront the real problems.

To pick on three big issues:-

Training: USN pilots had to be able to recover onto the carrier, so the pool of pilots to deploy to Yankee Station was limited. As a result, they tended to be better trained in type and more experienced, though also facing exhaustion and burnout since repeat tours were more common.

The USAF adopted a “no involuntary second tour” policy, meaning that relatively few experienced aircrews returned to the fray, and also that tanker, transport and bomber pilots were given a hasty conversion course and sent out as F-4 aircrew; often with air-to-air combat training missed altogether (it was the last part of the training, and so the most vulnerable to delays, bad weather or other problems).

Tactics: the USAF was wedded to a rigid four-plane formation called “fluid four” with two two-plane elements in relatively close formation (despite the name - it had been ‘fluid’ in 1940 but the USAF hadn’t updated the spacing for the jet age). The idea was that the formation provided mutual protection and support: the reality was that it was clumsy and awkward, with the wingmen (always the least experienced crews) spending more time on station-keeping and avoiding collisions, than on watching for enemy. Typically the flight leader was the only “shooter” with the rest of the flight delegated to cover him: the formation was popular with flight leads (who’d score any kills going) but dangerous for the rookies flying #3 and #4.

The USN used “loose deuce” formation with a more widely-spaced pair of aircraft, able to cover each other and both able to engage if opportunity arose: this was shown to be clearly superior in both training and combat, but for reasons not clear (because it was “a Navy formation”?) the USAF rejected it throughout the conflict.

Weapons: the AIM-7 Sparrow wasn’t very effective in Vietnam, having been designed for long-range engagements against Soviet bombers rather than dogfighting agile MiGs. In 1972 about 281 were fired for 34 kills (about 12%) with about two-thirds malfunctioning when fired (so the Sparrows that actually worked, weren’t too bad by then…). The USAF prioritised the Sparrow as a weapon (30 kills), with Sidewinder (nine kills) and guns (seven kills, all by F-4Es) secondary despite the fuss made over “lacking a gun” (the last two kills were where manoeuverings MiG crashed into the ground during dogfights or evasions)

Conversely, the USN scored twenty-three of their kills with Sidewinder and one with Sparrow. The USN used the AIM-9G Sidewinder, firing fifty for a 46% kill rate; the USN used the AIM-9E and AIM-9J Sidewinder, firing ninety-five for nine kills, or a 11% hit rate. Training was one issue, but the Navy Sidewinders (since the AIM-9D) used a nitrogen-cooled seeker which was more sensitive and better able to track an aircraft against terrain or cloud: the USAF had rejected that option, developing their own bespoke Sidewinders that proved less effective. Since the USAF aircraft didn’t have the nitrogen bottles for sensor cooling, the option of simply loading up AIM-9Gs wasn’t available (it wasn’t until the AIM-9L that the US services used the same short-range AAM)

There’s a definite impression of senior USAF looking at their performance and crossing off options. “Change training? No, too Navy. Change tactics? Can’t use Navy doctrine! Change missiles? Navy missiles, no way! What don’t the Navy do? Guns! That’s what we want!”

Very good and detailed history and analysis in the book “Clashes: Air Combat over Vietnam 1965–1972” by Marshal L. Michel III.

On the US side, missiles by about 3:1 (of about 200 enemy aircraft destroyed air-to-air, guns got about 50, missiles about 150). Although the missiles had various problems (the AIM-4 Falcon was very ill-suited to the conditions, the AIM-7 needed a lot of training to use correctly, the AIM-9 had limitations at first) they were much more effective than gunfire: the USN’s F-8 Crusaders (“the last gunfighters”) scored 19 kills for three losses, but 15 of those kills were with Sidewinder missiles and only four with guns. During 1972’s “Linebacker” campaigns, the US Navy shot down 24 enemy aircraft for four losses air-to-air, in Phantoms lacking any guns (and achieving a very high effectiveness with their missiles); the USAF, in the same period, downed 48 NVAF aircraft but lost 24 in return, despite their F-4D Phantoms having a gun pod and their F-4Es a built-in cannon (guns scored only seven of the 48 kills). Worth remembering, of course, that in 1967–68 during “Rolling Thunder”, the USAF were making heavy use of the F-105 Thunderchief, which had an internal gun but - more importantly - rarely carried missiles, especially on strike missions (with only four wing pylons, adding AAMs meant losing other, more useful payload); so in 1968, guns rose to nearly a third of the total (23 by Thuds). However, of 38 kills by USAF Phantoms, only eight were with the (podded) gun they had available. Marshal Michel III’s “Clashes” is an excellent study of the air-to-air fighting over Vietnam: while it would be rather too far to say that cannon armament on fighters was irrelevant, it was rather less critical than many claimed (though it was a convenient way to ignore a raft of failures of manning, training and tactics: much easier to blame poor performance on “no gun” than on institutional problems)

As a result, the USN achieved significantly better “kill ratios” in air-to-air combat: in 1972, over “Linebacker I” and “Linebacker II”, the USAF lost twenty-four aircraft to the NVAF while scoring 48 kills, for a 2:1 ratio (despite flying F-4D and F-4E Phantoms with either a centreline gunpod, or an internal M61 Vulcan). The USN shot down twenty-four MiGs for four air-to-air losses, for a 6:1 kill ratio despite using missiles alone.

Worse was the outcome of engagements: beyond the kill ratios, the NVAF engaged USN aircraft 26 times, while they clashed with the USAF on eighty-two occasions. So, on average, fighting the USN meant losing an aircraft for a one-in-seven chance of scoring a kill: as a result, the NVAF seemed to prioritise the USAF as targets despite their Phantoms having guns.

There were reasons behind all these factors: geography, politics, training structures and requirements, airbase layouts… but the upshot was that in the short term, the USAF found it easier to blame their “limited success” (a 2:1 kill ratio would usually be considered pretty good, but…) on being forced to fly a Navy aircraft that didn’t have the vital cannon (only seven of the 48 USAF kills were actually with cannon) rather than confront the real problems.

To pick on three big issues:-

Training: USN pilots had to be able to recover onto the carrier, so the pool of pilots to deploy to Yankee Station was limited. As a result, they tended to be better trained in type and more experienced, though also facing exhaustion and burnout since repeat tours were more common.

The USAF adopted a “no involuntary second tour” policy, meaning that relatively few experienced aircrews returned to the fray, and also that tanker, transport and bomber pilots were given a hasty conversion course and sent out as F-4 aircrew; often with air-to-air combat training missed altogether (it was the last part of the training, and so the most vulnerable to delays, bad weather or other problems).

Tactics: the USAF was wedded to a rigid four-plane formation called “fluid four” with two two-plane elements in relatively close formation (despite the name - it had been ‘fluid’ in 1940 but the USAF hadn’t updated the spacing for the jet age). The idea was that the formation provided mutual protection and support: the reality was that it was clumsy and awkward, with the wingmen (always the least experienced crews) spending more time on station-keeping and avoiding collisions, than on watching for enemy. Typically the flight leader was the only “shooter” with the rest of the flight delegated to cover him: the formation was popular with flight leads (who’d score any kills going) but dangerous for the rookies flying #3 and #4.

The USN used “loose deuce” formation with a more widely-spaced pair of aircraft, able to cover each other and both able to engage if opportunity arose: this was shown to be clearly superior in both training and combat, but for reasons not clear (because it was “a Navy formation”?) the USAF rejected it throughout the conflict.

Weapons: the AIM-7 Sparrow wasn’t very effective in Vietnam, having been designed for long-range engagements against Soviet bombers rather than dogfighting agile MiGs. In 1972 about 281 were fired for 34 kills (about 12%) with about two-thirds malfunctioning when fired (so the Sparrows that actually worked, weren’t too bad by then…). The USAF prioritised the Sparrow as a weapon (30 kills), with Sidewinder (nine kills) and guns (seven kills, all by F-4Es) secondary despite the fuss made over “lacking a gun” (the last two kills were where manoeuverings MiG crashed into the ground during dogfights or evasions)

Conversely, the USN scored twenty-three of their kills with Sidewinder and one with Sparrow. The USN used the AIM-9G Sidewinder, firing fifty for a 46% kill rate; the USN used the AIM-9E and AIM-9J Sidewinder, firing ninety-five for nine kills, or a 11% hit rate. Training was one issue, but the Navy Sidewinders (since the AIM-9D) used a nitrogen-cooled seeker which was more sensitive and better able to track an aircraft against terrain or cloud: the USAF had rejected that option, developing their own bespoke Sidewinders that proved less effective. Since the USAF aircraft didn’t have the nitrogen bottles for sensor cooling, the option of simply loading up AIM-9Gs wasn’t available (it wasn’t until the AIM-9L that the US services used the same short-range AAM)

There’s a definite impression of senior USAF looking at their performance and crossing off options. “Change training? No, too Navy. Change tactics? Can’t use Navy doctrine! Change missiles? Navy missiles, no way! What don’t the Navy do? Guns! That’s what we want!”

Very good and detailed history and analysis in the book “Clashes: Air Combat over Vietnam 1965–1972” by Marshal L. Michel III.

On the US side, missiles by about 3:1 (of about 200 enemy aircraft destroyed air-to-air, guns got about 50, missiles about 150). Although the missiles had various problems (the AIM-4 Falcon was very ill-suited to the conditions, the AIM-7 needed a lot of training to use correctly, the AIM-9 had limitations at first) they were much more effective than gunfire: the USN’s F-8 Crusaders (“the last gunfighters”) scored 19 kills for three losses, but 15 of those kills were with Sidewinder missiles and only four with guns. During 1972’s “Linebacker” campaigns, the US Navy shot down 24 enemy aircraft for four losses air-to-air, in Phantoms lacking any guns (and achieving a very high effectiveness with their missiles); the USAF, in the same period, downed 48 NVAF aircraft but lost 24 in return, despite their F-4D Phantoms having a gun pod and their F-4Es a built-in cannon (guns scored only seven of the 48 kills). Worth remembering, of course, that in 1967–68 during “Rolling Thunder”, the USAF were making heavy use of the F-105 Thunderchief, which had an internal gun but - more importantly - rarely carried missiles, especially on strike missions (with only four wing pylons, adding AAMs meant losing other, more useful payload); so in 1968, guns rose to nearly a third of the total (23 by Thuds). However, of 38 kills by USAF Phantoms, only eight were with the (podded) gun they had available. Marshal Michel III’s “Clashes” is an excellent study of the air-to-air fighting over Vietnam: while it would be rather too far to say that cannon armament on fighters was irrelevant, it was rather less critical than many claimed (though it was a convenient way to ignore a raft of failures of manning, training and tactics: much easier to blame poor performance on “no gun” than on institutional problems)