https://www.derekthompson.org/p/the-death-of-partying-in-the-usaand

https://archive.is/jFfZN

In January, The Atlantic's Ellen Cushing published an essay with an admirably blunt title: “Americans Need to Party More.” Burrowing into the appendix tables of the American Time Use Survey, she unearthed the fact that just 4.1 percent of Americans said they “attended or hosted” a party or ceremony on a typical weekend or holiday in 2023. In other words, in any given weekend, just one in 25 US households had plans to attend a social event.

The ATUS is a government questionnaire that asks a large sample of Americans how much time they spend doing just about everything, including sleeping, working, grooming themselves, playing with their pets, and going to parties. The latest ATUS estimates were published last month. The results emphatically affirm Cushing’s diagnosis: America’s social calendar is bare.

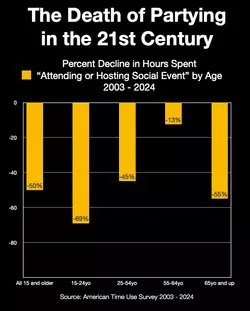

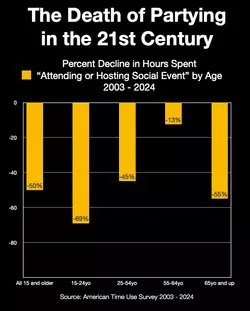

Between 2003 and 2024, the amount of time that Americans spent attending or hosting a social event declined by 50 percent. Almost every age group cut their party time in half in the last two decades. For young people, the decline was even worse. Last year, Americans aged 15-to-24 spent 70 percent less time attending or hosting parties than they did in 20031.

The death of the party fits into a broader social phenomenon that I called “The Anti-Social Century” in a cover story for The Atlantic. At a time of surging anxiety and mental distress, Americans spend more time alone today than in any period in recorded history. Face-to-face socializing has plummeted in the last two decades by about 20 percent. For unmarried men and people younger than 25, the decline exceeds 35 percent, which might explain why these groups seem to have fewer friends than ever.

Spelunking through the ATUS database for my article, I came across a number of jaw-dropping statistics about surging American solitude:

A Brief History of American Parties

Even with its Puritan influences, the U.S. has been a nation of party people for centuries. The historian Karen V. Hansen wrote that early 1800s New England was “a very social time.” Despite the fact that it was freezing half the year and cumbersome to get just about anywhere, Americans gathered regularly for maple syrup parties, quilting parties, and other events of extreme wholesomeness:

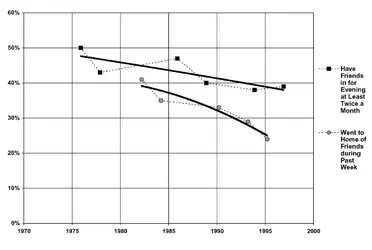

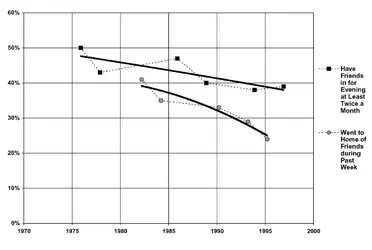

After the 1970s, Americans pulled back from just about every form of socializing. By the late 1990s, the share of Americans who said they visited the homes of friends in the previous week had declined by more than 40 percent. “Visits with friends are now on the social capital endangered species list,” Putnam wrote. And all this happened by 2000, before the real anti-social century even started.

The rise of individualism and solitude since 1970 has been all-encompassing. Practically every measure of social togetherness was walloped by Putnam’s account, including church attendance, labor union participation, and, yes, bowling leagues. Despite some critics who insist that every social phenomenon is a story about class, Putnam showed that these trends affected rich and poor alike. Whatever is happening, he said, it’s happening to just about all of us.

The Usual Suspects: Work, Parenthood, and Screens

I think the death of partying, like the anti-social century, emerges from a complicated set of factors, which spans labor economics, family dynamics, consumer technology, and modern psychology.

Putnam suggests—quite plausibly, but without much quantitative evidence—that women have long been the keepers of the family social calendar. Wives, not husbands, historically planned the quilting parties, the bridge games, and the neighborhood potlucks. But in the second half of the 20th century, many women swapped unpaid family jobs for salaried positions. In 1970, right around the inflection point of America’s social decline, the share of women between 25 and 54 who participated in the labor force surged past 50 percent for the first time; it’s currently near 80 percent. As more women poured their weekdays into 9-to-5 work, men failed to take over the logistical labor required to fill out the social calendar, and adult gatherings gradually eroded in the age of the dual-earner household2.

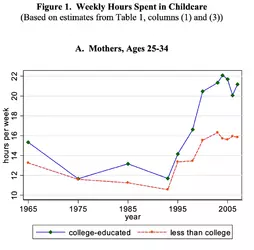

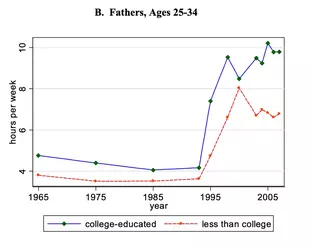

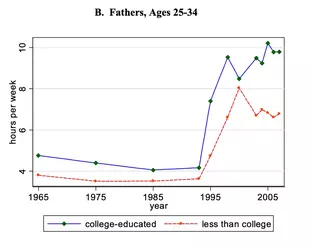

Meanwhile, parenting norms have changed. Americans used to have more kids whom they watched less; now they have fewer children whom they watch more. “Visions of neighborhoods full of stay-at-home mothers with children roaming freely from house to house, or yard to yard, in part reflect baby boomers’ nostalgic memories of childhood in the past,” the sociologists Liana C. Sayer, Suzanne M. Bianchi, and John P. Robinson wrote in 2004. Between 1975 and 1998, they found, mothers increased the amount of time they spent with their kids by about 200 minutes a week. For married fathers, the increase was even more dramatic—about 240 minutes per week. Parents are more anxious than they used to be, not only about neighborhood crime and playground accidents, but also about their children’s achievements.

In their famous paper "The Rug Rat Race," the economists Garey Ramey and Valerie Ramey wrote that childcare time surged again in the mid-1990s by more than 9 hours per week among college-educated parents. Fearing that their children might not get into the best colleges, these parents devoted more of their downtime to serving as frantic executive assistants to their offspring. It’s impossible to host a cocktail party when your second job is to be your son and daughter’s part-time limo driver who escorts them to 13 weekend extracurricular activities (that you kind of forced them to do, in the first place).

And then, there are the screens. The television landed in the US living room in the middle of the 20th century like an asteroid from deep space, displacing settled habits and sending ripples through the social fabric. Between 1965 and 1995, the typical American’s leisure time grew by about 300 hours a year, and we seem to have spent almost all those hours watching more TV. By the 1980s, people who said that television was their “primary form of entertainment” were less likely to engage in practically every other form of social interaction, Putnam found:

Many of us spend hours every week with our favorite TikTok stars, YouTube gurus, Instagram influencers, Twitter gadflies, podcast buddies, Reddit friends, and other people we kind of know and sort of care about, even though they might not even know we exist, at all. Keeping up with these people—watching them, listening to them, giving ourselves over to them—necessarily requires pulling our focus out of the world of flesh and blood. To be a citizen of the Internet is to spend hundreds of hours inside the minds of virtual people we couldn’t party with, even if we desperately wanted to.

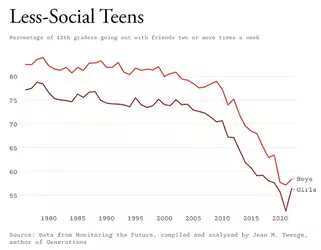

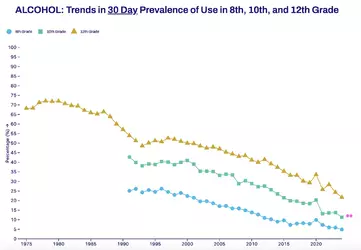

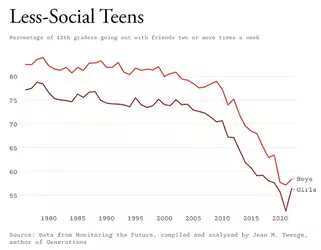

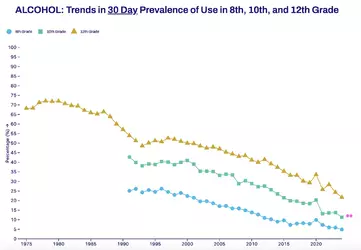

Finally, while one needn’t be drunk to have a good time with others, I cannot ignore the fact that the great American party deficit has coincided with an extraordinary decline in teen drinking. Last year was the first on record, going back to 1975, that fewer than 50 percent of high school seniors said they’d ever had a drink of alcohol. As recently as 1989, the share was higher than 90 percent. Eighth graders in the 1980s were more likely to say they had a sip of alcohol in the previous month than today’s 12th graders.

Disparaging today’s teenagers for their failure to binge-drink would be absurd. Still, I’d guess the decline of booze in the lives of young Americans is both a cause of reduced socializing and a driver of it. Young Americans go out less, so they drink less, so they have less interest in creating excuses to drink, so they throw fewer parties, so they go out less, so they drink less. These attitudes carry over into young adulthood. The share of 18- to 34-year-olds who say "drinking in moderation" is "bad for your health" has doubled in the last 20 years to 65 percent—far more than any other age group.

It would be easier for everyone—young people, parents, and commentators—if every social trend was either terrific or terrible. But like the rise of the dual-earner household, the turn against alcohol among the same young people whose socialization has plunged is a complicated phenomenon that defies easy good-bad categorization. I cannot deny that abstinence is good for young people’s livers; but I worry that it’s part of a larger set of behaviors that’s bad for their hearts.

I spent much of 2024 writing about two subjects—abundance and the anti-social century. Sometimes, I felt whiplash turning back and forth between them, with the former giving hope and the latter eliciting dread. Sometimes, however, I felt that the two pieces fit together with surprising and satisfying snap. I care about abundance, because I think American citizens deserve an agenda of augmentation; I want the U.S. to build and invent more of what we need. But I care about the anti-social century, because to paraphrase Marshall McLuhan, I know that some augmentations can also be amputations. When we use technology to extend our powers, we risk sacrificing something in the opposite direction. Sometimes these sacrifices are easy to see, such as the discovery of oil leading to the demise of the firewood industry, or the invention of the internal combustion engine causing the demise of the farm animal. But sometimes, progress incurs tradeoffs that are more subtle and only reveal themselves in time.

Today, I believe we’ve built ourselves a world of greater professional ambition, more intensive parenting, and lavish entertainment abundance. But in making this world, we’ve lost a bit of each other. If summoning these magnificent technologies incurs the death of our social lives, a permanent surge of anxiety, and the long-term demise of deep friendships, then we’ll have built ourselves a glittering dungeon of insularity and called it progress. Surely, we can do better than that.

1

I think it’s fair to point out that one year’s survey data can be statistically underpowered, especially as the cross-tab population sizes get smaller. But in this case, we’re looking at a social phenomenon that’s been happening for a while and has been replicated in year after year of ATUS data.

2

This is one of those paragraphs that could perhaps be screenshotted by someone who insists that I’m saying something wild, like women shouldn’t work, or that they ought to go back to their historical role of Family Party Planner. To be clear, I definitely do not think that. Rather, in keeping with the theme of this article’s conclusion, I think progress involves change, and change can have surprising costs. Plus: Hey, dudes, we have phones and calendars, too? We can plan stuff!

https://archive.is/jFfZN

In January, The Atlantic's Ellen Cushing published an essay with an admirably blunt title: “Americans Need to Party More.” Burrowing into the appendix tables of the American Time Use Survey, she unearthed the fact that just 4.1 percent of Americans said they “attended or hosted” a party or ceremony on a typical weekend or holiday in 2023. In other words, in any given weekend, just one in 25 US households had plans to attend a social event.

The ATUS is a government questionnaire that asks a large sample of Americans how much time they spend doing just about everything, including sleeping, working, grooming themselves, playing with their pets, and going to parties. The latest ATUS estimates were published last month. The results emphatically affirm Cushing’s diagnosis: America’s social calendar is bare.

Between 2003 and 2024, the amount of time that Americans spent attending or hosting a social event declined by 50 percent. Almost every age group cut their party time in half in the last two decades. For young people, the decline was even worse. Last year, Americans aged 15-to-24 spent 70 percent less time attending or hosting parties than they did in 20031.

The death of the party fits into a broader social phenomenon that I called “The Anti-Social Century” in a cover story for The Atlantic. At a time of surging anxiety and mental distress, Americans spend more time alone today than in any period in recorded history. Face-to-face socializing has plummeted in the last two decades by about 20 percent. For unmarried men and people younger than 25, the decline exceeds 35 percent, which might explain why these groups seem to have fewer friends than ever.

Spelunking through the ATUS database for my article, I came across a number of jaw-dropping statistics about surging American solitude:

Still, I’m not sure that anything I’ve found is more galling than the revelation that young people spend 70 percent less time partying today than they did 20 years ago, or that Americans in general have taken half their social calendar and set it on fire since the turn of the century.

- Men who watch television now spend 7 hours in front of the TV for every hour they spend hanging out with somebody outside their home.

- The typical female pet owner spends more time actively engaged with her pet than she spends in face-to-face contact with friends of her own species.

- Since the early 2000s, the amount of time that Americans say they spend helping or caring for people outside their nuclear family has declined by more than a third.

A Brief History of American Parties

Even with its Puritan influences, the U.S. has been a nation of party people for centuries. The historian Karen V. Hansen wrote that early 1800s New England was “a very social time.” Despite the fact that it was freezing half the year and cumbersome to get just about anywhere, Americans gathered regularly for maple syrup parties, quilting parties, and other events of extreme wholesomeness:

As Americans moved to cities, urbanization was “not fatal” to neighborly gatherings, Robert Putnam wrote in his book Bowling Alone. As late as the 1970s, the average US household entertained friends at home about 15 times a year and went out to a friend’s place about every other week. “One way or another, three-quarters of all Americans got together at home with friends” at least once a month, and “the national average was three such soirees per month,” he wrote.The many types of visiting ranged from pure socializing to communal labor: visitors took afternoon tea, made informal Sunday visits, attended maple sugar parties and cider tastings, stayed for extended visits, offered assistance in giving birth, paid their respects to the family of the deceased, participated in quilting parties, and raised houses and barns. Visits lasted from a brief stopover, or a “call,” to a leisurely afternoon, to a month-long stay. Visitors frequently stayed overnight. The difficulty of travel—particularly in winter, by foot, horse, stage, wagon, or train—created barriers to visiting but did not deter visitors who highly valued their contact with neighbors and kin. It was through visiting, in fact, that they created their communities.

After the 1970s, Americans pulled back from just about every form of socializing. By the late 1990s, the share of Americans who said they visited the homes of friends in the previous week had declined by more than 40 percent. “Visits with friends are now on the social capital endangered species list,” Putnam wrote. And all this happened by 2000, before the real anti-social century even started.

The rise of individualism and solitude since 1970 has been all-encompassing. Practically every measure of social togetherness was walloped by Putnam’s account, including church attendance, labor union participation, and, yes, bowling leagues. Despite some critics who insist that every social phenomenon is a story about class, Putnam showed that these trends affected rich and poor alike. Whatever is happening, he said, it’s happening to just about all of us.

The Usual Suspects: Work, Parenthood, and Screens

I think the death of partying, like the anti-social century, emerges from a complicated set of factors, which spans labor economics, family dynamics, consumer technology, and modern psychology.

Putnam suggests—quite plausibly, but without much quantitative evidence—that women have long been the keepers of the family social calendar. Wives, not husbands, historically planned the quilting parties, the bridge games, and the neighborhood potlucks. But in the second half of the 20th century, many women swapped unpaid family jobs for salaried positions. In 1970, right around the inflection point of America’s social decline, the share of women between 25 and 54 who participated in the labor force surged past 50 percent for the first time; it’s currently near 80 percent. As more women poured their weekdays into 9-to-5 work, men failed to take over the logistical labor required to fill out the social calendar, and adult gatherings gradually eroded in the age of the dual-earner household2.

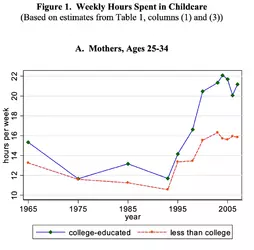

Meanwhile, parenting norms have changed. Americans used to have more kids whom they watched less; now they have fewer children whom they watch more. “Visions of neighborhoods full of stay-at-home mothers with children roaming freely from house to house, or yard to yard, in part reflect baby boomers’ nostalgic memories of childhood in the past,” the sociologists Liana C. Sayer, Suzanne M. Bianchi, and John P. Robinson wrote in 2004. Between 1975 and 1998, they found, mothers increased the amount of time they spent with their kids by about 200 minutes a week. For married fathers, the increase was even more dramatic—about 240 minutes per week. Parents are more anxious than they used to be, not only about neighborhood crime and playground accidents, but also about their children’s achievements.

In their famous paper "The Rug Rat Race," the economists Garey Ramey and Valerie Ramey wrote that childcare time surged again in the mid-1990s by more than 9 hours per week among college-educated parents. Fearing that their children might not get into the best colleges, these parents devoted more of their downtime to serving as frantic executive assistants to their offspring. It’s impossible to host a cocktail party when your second job is to be your son and daughter’s part-time limo driver who escorts them to 13 weekend extracurricular activities (that you kind of forced them to do, in the first place).

And then, there are the screens. The television landed in the US living room in the middle of the 20th century like an asteroid from deep space, displacing settled habits and sending ripples through the social fabric. Between 1965 and 1995, the typical American’s leisure time grew by about 300 hours a year, and we seem to have spent almost all those hours watching more TV. By the 1980s, people who said that television was their “primary form of entertainment” were less likely to engage in practically every other form of social interaction, Putnam found:

The effect of smartphones on our social lives is easily misunderstood. I don’t like the simplistic idea that smartphones are purely anti-social. Rather, I love the observation by Marc Dunkelman that digital technology has not obliterated our social connections but rather warped them. Americans today are in constant contact with the inner ring of family and the outer ring of "tribe"—that is, people we follow online, often because we share something in common, such as a sports allegiance or a political ideology. But the middle ring of community has atrophied. We know our online avatars better than we know our neighbors; we interact with certain online communities more than we text our friends. Smartphones and social media have expanded our circle of “parasocial” relationships at the expense of our actual social relationships.[They] work on community projects less often, attend fewer dinner parties and fewer club meetings, spend less time visiting friends, entertain at home less, picnic less, are less interested in politics, give blood less often, write friends less regularly, make fewer long-distance calls, send fewer greeting cards and less email, and express more road rage than demographically matched people who differ only in saying that TV is not their primary form of entertainment.

Many of us spend hours every week with our favorite TikTok stars, YouTube gurus, Instagram influencers, Twitter gadflies, podcast buddies, Reddit friends, and other people we kind of know and sort of care about, even though they might not even know we exist, at all. Keeping up with these people—watching them, listening to them, giving ourselves over to them—necessarily requires pulling our focus out of the world of flesh and blood. To be a citizen of the Internet is to spend hundreds of hours inside the minds of virtual people we couldn’t party with, even if we desperately wanted to.

Finally, while one needn’t be drunk to have a good time with others, I cannot ignore the fact that the great American party deficit has coincided with an extraordinary decline in teen drinking. Last year was the first on record, going back to 1975, that fewer than 50 percent of high school seniors said they’d ever had a drink of alcohol. As recently as 1989, the share was higher than 90 percent. Eighth graders in the 1980s were more likely to say they had a sip of alcohol in the previous month than today’s 12th graders.

Disparaging today’s teenagers for their failure to binge-drink would be absurd. Still, I’d guess the decline of booze in the lives of young Americans is both a cause of reduced socializing and a driver of it. Young Americans go out less, so they drink less, so they have less interest in creating excuses to drink, so they throw fewer parties, so they go out less, so they drink less. These attitudes carry over into young adulthood. The share of 18- to 34-year-olds who say "drinking in moderation" is "bad for your health" has doubled in the last 20 years to 65 percent—far more than any other age group.

It would be easier for everyone—young people, parents, and commentators—if every social trend was either terrific or terrible. But like the rise of the dual-earner household, the turn against alcohol among the same young people whose socialization has plunged is a complicated phenomenon that defies easy good-bad categorization. I cannot deny that abstinence is good for young people’s livers; but I worry that it’s part of a larger set of behaviors that’s bad for their hearts.

I spent much of 2024 writing about two subjects—abundance and the anti-social century. Sometimes, I felt whiplash turning back and forth between them, with the former giving hope and the latter eliciting dread. Sometimes, however, I felt that the two pieces fit together with surprising and satisfying snap. I care about abundance, because I think American citizens deserve an agenda of augmentation; I want the U.S. to build and invent more of what we need. But I care about the anti-social century, because to paraphrase Marshall McLuhan, I know that some augmentations can also be amputations. When we use technology to extend our powers, we risk sacrificing something in the opposite direction. Sometimes these sacrifices are easy to see, such as the discovery of oil leading to the demise of the firewood industry, or the invention of the internal combustion engine causing the demise of the farm animal. But sometimes, progress incurs tradeoffs that are more subtle and only reveal themselves in time.

Today, I believe we’ve built ourselves a world of greater professional ambition, more intensive parenting, and lavish entertainment abundance. But in making this world, we’ve lost a bit of each other. If summoning these magnificent technologies incurs the death of our social lives, a permanent surge of anxiety, and the long-term demise of deep friendships, then we’ll have built ourselves a glittering dungeon of insularity and called it progress. Surely, we can do better than that.

1

I think it’s fair to point out that one year’s survey data can be statistically underpowered, especially as the cross-tab population sizes get smaller. But in this case, we’re looking at a social phenomenon that’s been happening for a while and has been replicated in year after year of ATUS data.

2

This is one of those paragraphs that could perhaps be screenshotted by someone who insists that I’m saying something wild, like women shouldn’t work, or that they ought to go back to their historical role of Family Party Planner. To be clear, I definitely do not think that. Rather, in keeping with the theme of this article’s conclusion, I think progress involves change, and change can have surprising costs. Plus: Hey, dudes, we have phones and calendars, too? We can plan stuff!