Where European Energy Infrastructure Is Vulnerable to Attack

Bloomberg (archive.ph)

By Natalia Drozdiak, Anna Shiryaevskaya, and Todd Gillespie

2022-11-17T11:15:23

The landfall facility of the Baltic Sea gas pipeline Nord Stream 2 in Lubmin, Germany.

Photographer: Fabrizio Bensch/Reuters

On Sept. 26, seismologists detected a series of explosions that were quickly traced to the floor of the Baltic Sea. It soon became clear that the blasts had severed the Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines linking Russia with Germany. Many in the business suspected Russian President Vladimir Putin was responsible—something the Kremlin denies, instead blaming “Anglo-Saxons.”

The damage highlighted the vulnerability of Europe’s energy networks, which came into sharper focus in the following weeks as radio cables in Germany were cut, halting rail service for hours, and Norway began detecting “abnormally high” drone activity near its offshore energy installations. “We have seen a number of very strange physical attacks,” says Evangelos Ouzounis, head of policy development at the European Union’s cybersecurity agency. “The energy network is vast, and you cannot protect it physically.”

The pressure increased on Nov. 15 when a rocket struck a village in Poland, a NATO member, sparking concerns that the conflict could widen. Since the Nord Stream attacks, NATO members have increased monitoring with satellites, aircraft, ships and submarines, setting up something like an anti-drone shield for the North and Baltic seas. And the UK says it will invest in special ships to help secure undersea pipelines and data cables. “Russia wants to push the envelope and test the resolve of NATO,” says Kristine Berzina of the German Marshall Fund in Washington. Here’s a look at the facilities that are at the greatest risk.

The Most Vulnerable Sites

① Baltic Pipe

The pipeline can carry up to 10 billion cubic meters (353 billion cubic feet) of gas annually from Norway to Poland, via Denmark. It was inaugurated the day of the Nord Stream explosions and allows Poland and the Baltic states—all vehement opponents of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—to diversify energy supplies. Although its capacity is only a tenth of Nord Stream’s, every bit counts as energy prices in Europe stand at roughly four times historical levels, despite above-average temperatures that have cut demand recently. A break in the system would be a tough blow for Poland, which has little gas storage. And it would be an indirect hit on Ukrainians, about 1 million of whom have sought refuge in Poland.

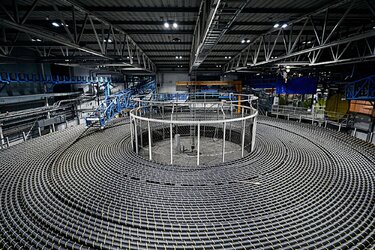

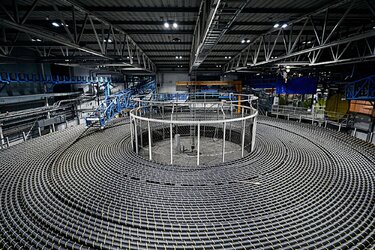

Manufacturing high-voltage cables in Sweden. Source: NKT

② ESTlink and ③ NordBalt

Cutting these undersea electricity cables would be both disruptive and highly symbolic, isolating the former Soviet Baltic republics from the European grid in Finland and Sweden, which have ended decades of non-alignment and plan to join NATO. The 700-megawatt NordBalt links Sweden and Lithuania. The two ESTlink cables, with a total capacity of 1,000MW, connect Estonia and Finland, which is anticipating rolling blackouts this winter after power imports from Russia were halted.

Klaipeda. Photographer: Paulius Peleckis/Getty Images

④ LNG Terminals

Liquefied natural gas has become a critical piece of the region’s response to the Kremlin’s cutoffs, and Lithuania’s import facility at Klaipeda—just up the coast from the Russian province of Kaliningrad—has been christened “Independence.” Germany is hiring as many as seven ships that can transfer the fuel to the gas grid; three are expected to start before yearend, including one in the coastal port of Lubmin, where Nord Stream makes landfall. Fearing an attack, Finland and Estonia have decided to operate a floating LNG terminal from a berth in the southern coastal town of Inkoo this winter.

Gas processing in Norway. Photographer: Cornelius Poppe/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

⑤ Europipe II and ⑥ Langeled

These pipelines carrying Norwegian gas to Germany and the UK look particularly vulnerable given that much of their path, covering more than 1,000 miles (1,609 kilometers), runs through extremely remote waters. “The worrying thing about what happened with Nord Stream is that it’s quite a busy area,” says Anne-Sophie Corbeau, a researcher at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

The Danish Navy at Bornholm. Photographer: Hannibal Hanschke/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

⑦ Bornholm Energy Island

Germany and Denmark’s €9 billion ($9.3 billion) offshore wind-power hub is still years away from operation, but the site is tough to protect, and an incident there would deal a bitter blow to European efforts to become energy independent. The EU, UK and US in May blamed Moscow for cyberattacks on a satellite network that impaired control of thousands of German wind turbines. “A wind farm doesn’t operate by itself,” says Patricia Schouker, an energy analyst at the Payne Institute for Public Policy in Colorado. “It’s connected, and Russia right now is testing those entry points and vulnerabilities.”

(Adds location of Finland LNG terminal in 6th paragraph.)

Bloomberg (archive.ph)

By Natalia Drozdiak, Anna Shiryaevskaya, and Todd Gillespie

2022-11-17T11:15:23

The landfall facility of the Baltic Sea gas pipeline Nord Stream 2 in Lubmin, Germany.

Photographer: Fabrizio Bensch/Reuters

On Sept. 26, seismologists detected a series of explosions that were quickly traced to the floor of the Baltic Sea. It soon became clear that the blasts had severed the Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines linking Russia with Germany. Many in the business suspected Russian President Vladimir Putin was responsible—something the Kremlin denies, instead blaming “Anglo-Saxons.”

The damage highlighted the vulnerability of Europe’s energy networks, which came into sharper focus in the following weeks as radio cables in Germany were cut, halting rail service for hours, and Norway began detecting “abnormally high” drone activity near its offshore energy installations. “We have seen a number of very strange physical attacks,” says Evangelos Ouzounis, head of policy development at the European Union’s cybersecurity agency. “The energy network is vast, and you cannot protect it physically.”

The pressure increased on Nov. 15 when a rocket struck a village in Poland, a NATO member, sparking concerns that the conflict could widen. Since the Nord Stream attacks, NATO members have increased monitoring with satellites, aircraft, ships and submarines, setting up something like an anti-drone shield for the North and Baltic seas. And the UK says it will invest in special ships to help secure undersea pipelines and data cables. “Russia wants to push the envelope and test the resolve of NATO,” says Kristine Berzina of the German Marshall Fund in Washington. Here’s a look at the facilities that are at the greatest risk.

The Most Vulnerable Sites

① Baltic Pipe

The pipeline can carry up to 10 billion cubic meters (353 billion cubic feet) of gas annually from Norway to Poland, via Denmark. It was inaugurated the day of the Nord Stream explosions and allows Poland and the Baltic states—all vehement opponents of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—to diversify energy supplies. Although its capacity is only a tenth of Nord Stream’s, every bit counts as energy prices in Europe stand at roughly four times historical levels, despite above-average temperatures that have cut demand recently. A break in the system would be a tough blow for Poland, which has little gas storage. And it would be an indirect hit on Ukrainians, about 1 million of whom have sought refuge in Poland.

Manufacturing high-voltage cables in Sweden. Source: NKT

② ESTlink and ③ NordBalt

Cutting these undersea electricity cables would be both disruptive and highly symbolic, isolating the former Soviet Baltic republics from the European grid in Finland and Sweden, which have ended decades of non-alignment and plan to join NATO. The 700-megawatt NordBalt links Sweden and Lithuania. The two ESTlink cables, with a total capacity of 1,000MW, connect Estonia and Finland, which is anticipating rolling blackouts this winter after power imports from Russia were halted.

Klaipeda. Photographer: Paulius Peleckis/Getty Images

④ LNG Terminals

Liquefied natural gas has become a critical piece of the region’s response to the Kremlin’s cutoffs, and Lithuania’s import facility at Klaipeda—just up the coast from the Russian province of Kaliningrad—has been christened “Independence.” Germany is hiring as many as seven ships that can transfer the fuel to the gas grid; three are expected to start before yearend, including one in the coastal port of Lubmin, where Nord Stream makes landfall. Fearing an attack, Finland and Estonia have decided to operate a floating LNG terminal from a berth in the southern coastal town of Inkoo this winter.

Gas processing in Norway. Photographer: Cornelius Poppe/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

⑤ Europipe II and ⑥ Langeled

These pipelines carrying Norwegian gas to Germany and the UK look particularly vulnerable given that much of their path, covering more than 1,000 miles (1,609 kilometers), runs through extremely remote waters. “The worrying thing about what happened with Nord Stream is that it’s quite a busy area,” says Anne-Sophie Corbeau, a researcher at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

The Danish Navy at Bornholm. Photographer: Hannibal Hanschke/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

⑦ Bornholm Energy Island

Germany and Denmark’s €9 billion ($9.3 billion) offshore wind-power hub is still years away from operation, but the site is tough to protect, and an incident there would deal a bitter blow to European efforts to become energy independent. The EU, UK and US in May blamed Moscow for cyberattacks on a satellite network that impaired control of thousands of German wind turbines. “A wind farm doesn’t operate by itself,” says Patricia Schouker, an energy analyst at the Payne Institute for Public Policy in Colorado. “It’s connected, and Russia right now is testing those entry points and vulnerabilities.”

(Adds location of Finland LNG terminal in 6th paragraph.)