The thing about "wrongdoing" is that it itself has to be proved in court. I think you would have to convict Aaron of Witness tampering (or at least get a finding to that effect) in order to invoke the rule

This also requires a lot more than just some retard on the internet saying "wouldn't it be great if these people who are scheduled to testify against me would not show up??".

Unless Aaron paid them or told them "do not show up OR ELSE!", Nick can go shove a Balldo up his ass and spin.

Unfortunately for Aaron, Minnesota's treatment of that doctrine is disturbingly broad, first off because the state doesn't even need to prove the forfeiture by wrongdoing elements beyond a reasonable doubt, and instead has the luxury of the preponderance of the evidence (i.e. 51%) burden of proof used in civil cases:

The state's burden of proof on forfeiture is a preponderance of the evidence. See Davis/Hammon, 126 S.Ct. at 2280 ("[F]ederal courts using

Federal Rule of Evidence 804(b)(6), which codifies the forfeiture doctrine, have generally held the Government to the

preponderance-of-the-evidence standard, * * *. tate courts tend to follow the same practice * * *." (citations omitted)).

See also United States v. Balano, 618 F.2d 624, 629 (10th Cir. 1979)...

State v. Wright (Wright III), 726 N.W.2d 464, 479 n. 7 (Minn. 2007).

Secondly and even worse, the state doesn't need to find

direct evidence like some smoking-gun email showing threats or some wire transfer showing a bribe, and instead the judge can rely on a smattering of

circumstantial evidence to engage in speculation about whether attempts to pressure a witness were what

probably caused the witness' absence that could have just as easily been caused by a flat tire:

Shaka contends that there is no direct evidence that his conduct procured S.S.’s unavailability. He is correct. But the state argues that the district court was permitted to draw inferences from the evidence to determine whether Shaka caused S.S.’s unavailability. To resolve the issue raised by the parties, we first consider the difference between direct and circumstantial evidence and then analyze caselaw from other jurisdictions. The supreme court has defined direct evidence as "evidence that is based on personal knowledge or observation and that, if true, proves a fact without inference or presumption."

Bernhardt v. State, 684 N.W.2d 465, 477 n.11 (Minn. 2004) (citation omitted). Circumstantial evidence is defined as "evidence based on inference and not on personal knowledge or observation" and "all evidence that is not given by eyewitness testimony."

Id. (citation omitted). The supreme court has concluded that "

[c]ircumstantial evidence is entitled to the same weight as direct evidence."

Id. at 477.

In

State v. Maestas, the New Mexico Supreme Court held that causation in

the forfeiture-by-wrongdoing exception "need not be established by direct evidence or testimony" because "rarely will a witness who has been persuaded not to testify regarding an underlying crime come forward to testify about the persuasion."

412 P.3d 79, 90-91 (N.M. 2018 );

see also State v. Weathers, 219 N.C.App. 522, 724 S.E.2d 114, 117 (2012), ("It would be nonsensical to require that a witness

testify against a defendant in order to establish that the defendant has intimidated the witness into

not testifying.")

Likewise, in

United States v. Scott, the Seventh Circuit stated that "it seems almost certain that, in a case involving coercion or threats, a witness who refuses to testify at trial will not testify to the actions procuring his or her unavailability."

284 F.3d 758, 764 (7th Cir. 2002). Scott observed that

it "would not serve the goal of [Fed. R. Evid.] 804(b)(6) to hold that circumstantial evidence cannot support a finding of coercion."

Id.

Because Minnesota has recognized that direct and circumstantial evidence carry the same weight, we hold that a district court may draw reasonable inferences from circumstantial evidence in determining whether a defendant’s wrongdoing procured the unavailability of a witness.

State v. Shaka, 927 N.W.2d 762, 768-70 (Minn. Ct. App. 2019).

Third and worst, even under these loose burdens of proof the state doesn't even need to show any criminal or illegal conduct like the sorts of actual injury or threats meeting the

statutory definition of witness tampering or the sort of quid pro quo meeting the

statutory definition of bribery of a witness for the judge to find sufficient "wrongdoing" for forfeiture of Confrontation Clause rights to apply. In this particular context the "wrongdoing" is instead any effect upon witnesses that intentionally undermines the integrity of the judicial process, which can include any mere pressuring or influencing of witnesses that would be perfectly legal in other contexts:

Betancourt argues that even if the evidence about the content of his conversations with his mother is admissible, those conversations do not constitute evidence of wrongful conduct or that he intended to procure the unavailability of the witnesses. He asserts that his request to his mother to have the witnesses change their statements is consistent with his right to be presumed innocent and was only a plea to have the witnesses be truthful. But, in addition to evidence of Betancourt's conversations asking his mother to get the witnesses to change their statements, the record contains evidence of D.S.'s statements to his probation officer and the victims-services representative that he and A.S. were pressured by relatives not to cooperate with the prosecution.

"While defendants have no duty to assist the tate in proving their guilt, they do have the

duty to refrain from acting in ways that destroy the integrity of the criminal-trial system."

Davis v. Washington, 547 U.S. 813, 833, 126 S. Ct. 2266, 2280 (2006). ... In

Cox, the supreme court explained that "[t]he forfeiture-by-wrongdoing exception is aimed at defendants who intentionally

interfere with the judicial process."

779 N.W.2d at 850.

State v. Betancourt, A13-0732, 10-11 (Minn. Ct. App. Dec. 30, 2013)

More to the point, although cases in Minnesota and the Eighth Circuit encompassing Minnesota haven't precisely defined the scope of sufficient "wrongdoing" beyond the above clarification in

Betancourt, the way

Shaka above favorably cited the Seventh Circuit's

Scott case on a separate issue suggests that they'd just as easily adopt

Scott's definition of "wrongdoing" which is so broad as to include even applying any "pressure" or "undue influence" to a witness regardless of whether doing so was illegal or not:

Rule 804(b)(6) requires, first, that Scott engage in "wrongdoing." That word is not defined in the text of Rule 804(b)(6), although the advisory committee's notes point out that "wrongdoing" need not consist of a criminal act. One thing seems clear: causing a person not to testify at trial cannot be considered the "wrongdoing" itself, otherwise the word would be redundant. So we must focus on the actions procuring the unavailability. Scott argues his actions were not sufficiently evil because they were not akin to murder, physical assault, or bribery. Although such malevolent acts are clearly sufficient to constitute "wrongdoing," they are not necessary.

The notes make clear that the rule applies to all parties, including the government. Although, in the ugliest criminal cases, murder and physical assaults are all too possible on the defendant's side, it seems unlikely that the rule was needed to curtail government murder of potential witnesses. Rather, it contemplates application against the use of coercion, undue influence, or pressure to silence testimony and impede the truth-finding function of trials.

U.S. v. Scott, 284 F.3d 758, 763-64 (7th Cir. 2002)

That said, even under such a wishy-washy standard it's not at all clear that Nick will even end up being right by accident, because outside of any DMs and calls that Aaron and Geanu decline to discuss publicly, there's not even circumstantial evidence of Aaron even so much as pressuring or unduly influencing Geanu to cause them to do anything other than what they were already going to do anyway: go be truthful if they're forced to go, or blow off this annoying hassle altogether if they're not forced to go. Aaron and Geanu appearing "affable" on stream is definitely not enough, "just jokes" on stream about what a trial would hypothetically be like in their absence is probably not enough, and Nick is retarded if he thinks the state won't need more to put on the record. A search warrant for Aaron and Geanu's private communications could maybe get there, or Geanu snaking Aaron with disclosure of everything he's said to them could maybe get there, but barring some major breakthrough along those lines there's no shot at piercing the Confrontation Clause in this case. Not a fucking chance.

My guess is that this is Nick's way of setting up damage control in advance of what he suspects is coming up, so that after the case gets thrown out over failure to produce indispensable witnesses, he could still throw out the cope that he was always right about his brilliant Rule 804(b)(6) masterstroke and "if only the retarded prosecutor had listened" to him they

would have had Aaron dead to rights, and it's not on him if they chickened out. This is just more of the same "what-if" cope seen in how he continued to defend his Franks motion even

after it and its interlocutory appeal had been denied, so that he and every sycophant could still fantasize about how his glorious post-trial appeal

would have prevailed in some parallel timeline if only the damned gubmint hadn't forced him into a plea for the sake of his family and his mental health. Same shit, different day.

For whatever it's worth, Keanu told Ralph if they are subpoenaed, they will comply.

She didn't even go that far necessarily, and it was just that "if we have to go, we will go." For example Minnesota subpoenas for Geanu have already been issued to make them feel like they're "subpoenaed" but that doesn't mean they "have to go" even if they get personally served with those, and even if and when they get served with papers from the eventual New York proceeding (oddly still not filed for some reason), they

still would not yet "have to go" since there would be an opportunity to have their challenges heard in that New York proceeding. It would not be until a final order denying their challenge in the New York proceeding

and an order denying a stay of the order's enforcement pending appeal (or an adverse appellate decision following such a stay) that they would, at long last, actually "have to go." Whether all that shit would get done before May or whether the trial would be postponed for it all still remains to be seen.

Oh man is this the Frank’s hearing all over again?

Knowing in some detail Rekieta's brief and dismal history as a failed strip mall attorney, it's hard to take his lawyerly moments seriously. My legal background consists of sporadically watching Law & Order re-runs and I'd trust me over him as counsel in a legal dispute.

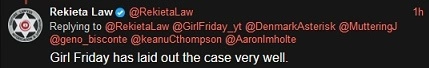

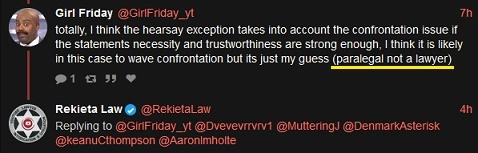

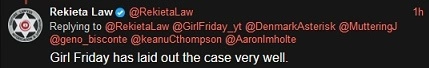

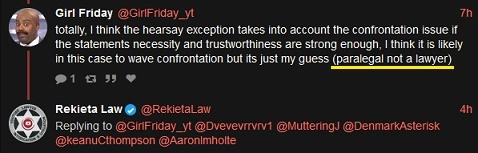

IDK, this time he's not alone with top legal minds backing him up on this one and working around the clock, so Aaron's attorney ought to be shakin' in his boots:

[X] [A]

[X] [A]

[X] [A]

[X] [A]