How regression taught me to live a grown-up life.

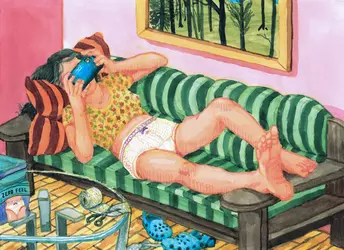

Illustration by Juan Bautista Climént Palmer

By Dani Blum

Oct. 28, 2025

“You’re going to molt like a baby snake,” one of the doctors said. He was right: I shed fragments of myself all over my studio apartment. Flakes of dead skin fell out of my laptop, my sheets, my couch. Scraps of singed flesh stuck to my rug. For that week when I could not fully walk, I inched from the bed to the couch, from the couch to the desk chair smothered in bandages and gauze and teeny packets of antibiotic ointment. My world narrowed to my apartment’s 500 square feet and the cheery purple packaging of the adult diapers that defined my recovery.

The simplest way to explain what happened is this: Last winter, my shower exploded. One minute, it was a normal shower; the next, scalding water sprayed from the shower head. I leaped out. For a few minutes, my brain stilled with shock’s synthetic calm. In the mirror, I saw that my left arm and thigh and chunks of my back and butt were scarlet. I started to scream. The pain was psychedelic. Walls bent; floors wobbled.

The carousel of doctors I saw over the next few days gave me detailed instructions on how to tend to my second-degree burns. This included wearing adult diapers, not to help me relieve myself but to hold my bandages in place and protect my wounds.

The diapers were, initially, a horrific indignity. They came with pink bows stamped on them. Some were dyed peach. Others had little lilac scallops that trailed along my waist, an attempt to preserve my femininity, I suppose, or to fool me into thinking that this was normal, even sexy, underwear. Even with no one around to witness me in my feeble state, I was embarrassed by how frail I was, humiliated by how little my body could do. I grumbled to my older sister that the diapers were practice for getting old.

“They’re practice for postpartum,” she shot back.

I had sworn, for most of my 20s, that I did not want children, but as I rounded my late 20s, any certainty about that crumbled. Sometimes, like when I saw a baby on the train, I felt flashes of physical, tangible yearning so strong that it scared me. But now I felt more like an infant than anyone capable of caring for one. The burns on my thigh forced me to relearn how to walk; I cried constantly. For a week, I only left my apartment to inch into cabs that shuttled me to doctors. I wore adult diapers all day and all night. Pain punctured my sleep, and I often bolted up to make sure my diaper was covering my torn-up skin.

I woke up each morning with swollen, pus-filled blisters dangling off my thigh, my arm, my back. I hauled myself back to the shower several times each day to wash off my wounds. Soap snagged in the tattered patches of my skin and felt like shattered glass being ground into my leg.

When I limped out, I smothered on antibacterial goop, clamped gauze over my stinging skin and dragged a fresh adult diaper up my leg. It was my padded support system, my safety net. I abandoned any pretense of ego, any claim I had to what I thought constituted adulthood. As my cells strained to stitch themselves together, there was so little I could control. The diapers should have been the most mortifying part. Instead, they held me together.

Any language I had for the burns seemed inadequate; I was scared and dazed and so focused on the physical. Gradually, though, I was able to leave my apartment. At January’s end, I slid off a diaper for the last time in a burn-center bathroom. Afterward, I went back to cotton underwear that felt newly flimsy. I don’t miss the diapers, but I miss what they offered: the constant reminder that I could tend to myself, my tiny shred of stability when my life and body were upended. I had seen the diapers as a sign of weakness at first, but day after day, they became a signal that I was capable. Here I was, so careful, so dutiful, taking this absurd extra step to keep myself safe. And they worked: I made it through the riskiest stage of wound care without an infection.

My late 20s had given me a sense of invulnerability. I could date someone for a few months or try out one thing or another — rock climbing, a soccer league, a month in Stockholm — and the contours of my life would reset to a base line. I told myself that this was proof of how capable I was, how competent — that I had designed a life that felt impenetrable.

The diapers, though, demanded surrender. We’re born into diapers, and we age back into them. I had thought I had several decades before my homecoming. I was 28 when I got burned, five days into a new year that I promised myself, as I did every year, would be different. I had lived in my studio apartment for four years, a college amount of time; I had worked the same job, kept the same friends, haunted the same cluster of bars and clubs. I kept waiting for someone to tell me what I should want: to have children, to move, to mark my adulthood in any other way than the years drifting by.

I felt so ill equipped and unprepared, and still, in my diaper days, I was getting a crash course in the beats of early parenting — the uncontrollable ache, the sleepless nights in my confined space, the incessant questions. The mound of diapers gave me the proof that I could take care of myself. They signaled that, at some point, I might be able to take care of someone else.

Dani Blum is a journalist and essayist who works as a health reporter for The New York Times. She lives in Brooklyn.

Dani Blum is a health reporter for The Times.