That reminds me of a story someone who works at Baen told. They had originally commissioned a Larry Elmore cover painting for Larry Correia's Son of the Black Sword, but then they had to change it because Barnes and Noble refused to carry it with that cover. They said it made the book look "old."What’s really going to bake your noodle is that sometimes they’re not going for readers with their shitty covers but buyers further up the distribution chain. I remember an anecdote that there used to be this one buyer lady for department stores who was more likely to approve books with “dresses” on the cover. All of a sudden every middling YA novel had a cover with a girl wearing a dress.

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

YABookgate

- Thread starter Puddleduck

- Start date

- Joined

- Apr 10, 2021

It'd stick out from all the other garbage covers.That reminds me of a story someone who works at Baen told. They had originally commissioned a Larry Elmore cover painting for Larry Correia's Son of the Black Sword, but then they had to change it because Barnes and Noble refused to carry it with that cover. They said it made the book look "old."

Hirbowedge

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Apr 19, 2021

Dragonlance novels were the first real books I can remember reading as a kid. I have no idea what drew me to get my parents to buy this book all those years ago, but the covers probably did have something to do with it. (The version I have has the same artwork, but the borders are prettier without the crappy D&D branding.)

- Joined

- Jan 31, 2020

That reminds me of a story someone who works at Baen told. They had originally commissioned a Larry Elmore cover painting for Larry Correia's Son of the Black Sword, but then they had to change it because Barnes and Noble refused to carry it with that cover. They said it made the book look "old."

View attachment 3709531View attachment 3709532

Oh yeah, I've heard that story too. Baen's still pissed about that - especially since Barnes & Noble pulled that stunt on an author with well over one million books sold.

Larry's now sold between three and five million books, and Forgotten Warrior is his least selling series - in part because some punk suit at B&N demanded boring covers for it.

- Joined

- Apr 13, 2021

@Flexo Maybe we should just ping an admin and add a secondary OP to the thread and retitle it, its imo obvious that YAgate is just symptomatic of a much broader rot in the industry than just wine aunts writing for other wine aunts.

Now to report some sad news Eric Flint's Ring of Fire Press is going under and filing for chapter 7 bankruptcy which means no more grantville gazette and no more very obscure side stories in the 1632 universe, also i lost a ton of books that i bought on there.

Now to report some sad news Eric Flint's Ring of Fire Press is going under and filing for chapter 7 bankruptcy which means no more grantville gazette and no more very obscure side stories in the 1632 universe, also i lost a ton of books that i bought on there.

- Joined

- Apr 10, 2021

Since this is basically a general thread now, I have to say the latest Writing Excuses on structure didn't want to make me shoot myself after having the misfortune to listen to twenty seconds of that troon talking about degenerate sex last ep. The whole series has been pissing me off since they brought in all these nobodies with 'diverse viewpoints'. The only female guest worth a damn who didn't talk about stupid woke shit or how hard she's had it was the Sri Lankan Mary Anne Mohanraj. I'm not checking anything she's done or twitter just in case. I'd be happy if they got rid of that empty carton cat lady Mary Robinette for her.

- Joined

- Nov 15, 2016

This word salad is absolutely amazing. I read through it twice and I'm STILL not sure what the thesis was, other than that (a) white people are bad and evil and keep publishing all to themselves and (b) BookScan should be free and publicly available because then we can see how the bad and evil WiPiPo in publishing are keeping the brave and virtuous PoC down and off bookstore shelves. Or something.

And for a supposed Data Scientist the author of this ignores the big problem with public library borrows: Namely if the book isn't on the shelf nobody can borrow it. As in the Boston Public Library's Overdrive site has 20 ebooks (plus a listing for a forward he wrote) and 2 audiobooks by John Scalzi for borrowing and 1 ebook and no audiobooks by Larry Correia. Whether this is due to Tor pushing for libraries more or librarians being biased in favor of Scalzi over Correia, who can say? Maybe Scalzi just sells better, but better by a factor of twenty? In any event, any data from the Boston Public Library would make Scalzi look pretty good and Correia like a nobody.

Anyhoo, enjoy.

WHERE IS ALL THE BOOK DATA? / https://archive.ph/ESCu6

10.4.2022

DIGITAL HUMANITIES

Y MELANIE WALSH

Culture industries increasingly use our data to sell us their products. It’s time to use their data to study them. To that end, we created the Post45 Data Collective, an open access site that peer reviews and publishes literary and cultural data. This a partnership between the Data Collective and Public Books, a series called Hacking the Culture Industries, brings you data-driven essays that change how we understand audiobooks, bestselling books, streaming music, video games, influential literary institutions such as the New York Times and the New Yorker, and more. Together, they show a new way of understanding how culture is made, and how we can make it better.

—Laura McGrath and Dan Sinykin

BY MELANIE WALSH

Culture industries increasingly use our data to sell us their products. It’s time to use their data to study them. To that end, we created the Post45 Data Collective, an open access site that peer reviews and publishes literary and cultural data. This a partnership between the Data Collective and Public Books, a series called Hacking the Culture Industries, brings you data-driven essays that change how we understand audiobooks, bestselling books, streaming music, video games, influential literary institutions such as the New York Times and the New Yorker, and more. Together, they show a new way of understanding how culture is made, and how we can make it better.

—Laura McGrath and Dan Sinykin

After the first lockdown in March 2020, I went looking for book sales data. I’m a data scientist and a literary scholar, and I wanted to know what books people were turning to in the early days of the pandemic for comfort, distraction, hope, guidance. How many copies of Emily St. John Mandel’s pandemic novel Station Eleven were being sold in COVID-19 times compared to when the novel debuted in 2014? And what about Giovanni Boccaccio’s much older—14th-century—plague stories, The Decameron? Were people clinging to or fleeing from pandemic tales during peak coronavirus panic? You might think, as I naively did, that a researcher would be able to find out exactly how many copies of a book were sold in certain months or years. But you, like me, would be wrong.

I went looking for book sales data, only to find that most of it is proprietary and purposefully locked away. What I learned was that the single most influential data in the publishing industry—which, every day, determines book contracts and authors’ lives—is basically inaccessible to anyone beyond the industry. And I learned that this is a big problem.

The problem with book sales data may not, at first, be apparent. Every week, the New York Times of course releases its famous list of “bestselling” books, but this list does not include individual sales numbers. Moreover, select book sales figures are often reported to journalists—like the fact that Station Eleven has sold more than 1.5 million copies overall—and also shared through outlets like Publishers Weekly. However, the underlying source for all these sales figures is typically an exclusive subscription service called BookScan: the most granular, comprehensive, and influential book sales data in the industry (though it still has significant holes—more on that to come).

Since its launch in 2001, BookScan has grown in authority. All the major publishing houses now rely on BookScan data, as do many other publishing professionals and authors. But, as I found to my surprise, pretty much everybody else is explicitly banned from using BookScan data, including academics. The toxic combination of this data’s power in the industry and its secretive inaccessibility to those beyond the industry reveals a broader problem. If we want to understand the contemporary literary world, we need better book data. And we need this data to be free, open, and interoperable.

Fortunately, there are a number of forward-thinking people who are already leading the charge for open book data. The Seattle Public Library is one of the few libraries in the country that releases (anonymized) book checkout data online, enabling anyone to download it from the internet for free. It isn’t book sales data, but it’s close. And such data might help us understand how the popularity of certain books fluctuates over time and in response to historical events like the COVID-19 pandemic (especially if more libraries around the country join the open data effort). Literary scholars have also begun to compile “counterdata” about the publishing industry. Richard So, a professor of English and cultural analytics at McGill University, and Laura McGrath, an English professor at Temple University, have respectively collected data about the race and ethnicity of authors published by mainstream publishing houses. Through their work, So and McGrath each prove that the Big Five houses have historically been dominated by white authors and that they continue to systematically reinforce whiteness today.

While all of this data is powerful in its own right, it becomes even more powerful if we can combine it all together: if we can merge author demographic data with library checkout data or with other literary trends. This promise anchors the Post45 Data Collective, an open-access repository for literary and cultural data that was founded by McGrath and Emory professor Dan Sinykin, and that I now lead as a coeditor with Sinykin. One of the goals of the repository is to help researchers get credit for the data that they painstakingly collect, clean, and share. But a broader goal is to share free cultural data with anybody who wants to reuse and recombine it to better understand contemporary literature, music, art, and more.

Now, I am pleased to introduce a Public Books series that honors and revolves around the Post45 Data Collective, and that will hopefully add to it and strengthen it. This series, Hacking the Culture Industries, demonstrates how corporate algorithms and data are shaping contemporary culture; but it also reveals how the same tools, in different hands, can be used to study, understand, and critique culture and its corporate influences in turn. Each of the authors in this series takes on a different kind of cultural data—from New Yorker short stories to Spotify music trends, from New York Times reviews to audiobook listening patterns. (Some of the data featured in these essays will also be published in, or is already available through, the Post45 Data Collective, enabling further research and exploration.)

I will say more about this series below, but first I want to focus on the broader significance of the Post45 Data Collective’s mission: to make book data (and other kinds of cultural data) free and open to the public.

To people who care about literature, data is often seen as a neoliberal bogeyman, the very antithesis of literature and possibly even what’s ruining literature. Plus, people tend to think that data is boring. To be fair, data is sometimes a neoliberal bogeyman, it is sometimes boring, and it may in fact be making literature more boring (more on that to come, too). But that’s precisely why we need to pay attention to it.

Corporate data already deeply influences the contemporary literary world, as revealed both here and in the broader essay series. And so, if you care about books, you should probably care about book data.

BookScan’s influence in the publishing world is clear and far-reaching. To an editor, BookScan numbers offer two crucial data points: (1) the sales history of the potential author, if it exists, and (2) the sales history of comparable, or “comp,” titles. These data points, if deemed unfavorable, can mean a book is dead in the water.

Take it from freelance editor Christina Boys, whom I spoke with over email, and who worked for 20 years as an editor at two of the Big Five publishing houses (Simon & Schuster and Hachette Book Group). Boys told me that BookScan data is “very important” for deciding whether to acquire or pass on a book; BookScan is also used to determine the size of an advance, to dictate the scale of a marketing campaign or book tour, and to help sell subsidiary rights like translation rights or book club rights. “A poor sales history on BookScan often results in an immediate pass,” Boys said.

Clayton Childress, a sociologist at the University of Toronto, came to similar conclusions in his 2012 study of BookScan data, in which he interviewed and observed more than 40 acquisition editors from across the country. Bad book sales numbers can haunt an author “like a bad credit score,” Childress reported, and they can “caus[e] others to be hesitant to do business with them because of past failures.”1

According to editors like Boys, the sway of book sales figures has siphoned much of the creativity and originality out of contemporary book publishing. “There’s less opportunity to acquire or promote a book based on things like gut instinct, quality of the writing, uniqueness of an idea, or literary or societal merit,” Boys claimed. “While passion—arguing that a book should be published—still matters, using that as a justification when it’s contrary to BookScan data has become increasingly challenging.” In a similar vein, Anne Trubek, the founder and publisher of the independent press Belt Publishing, told me that BookScan data is a strong conservative force in the industry—one of the reasons, though not the only reason, that Belt Publishing stopped subscribing after only one year. Trubek says that BookScan data encourages publishers to keep recycling the same kinds of books that sold well in the past. “I didn’t want to be a publisher who was working that way,” she elaborated. “That was not interesting. I think a lot of Big Five publishing is driven by data, and I think that things end up much more unimaginative as a result.”

Despite these claims, other publishing professionals maintain that BookScan data has not changed their work quite as dramatically. Childress interviewed one editor who explained that he manages to use BookScan data in creative ways to support his own independent choices.2 Yet even when editors find inventive ways to use BookScan data and to preserve their own aesthetic judgment, it is striking that they must still use and reckon with BookScan data in some form.

Perhaps most importantly, however, it is likely that books end up much more racially homogenous—that is, white—as a result of BookScan data, too. For example, in McGrath’s pioneering research on “comp” titles (the books that agents and editors claim are “comparable” to a pitched book), she found that 96 percent of the most frequently used comps were written by white authors. Because one of the most important features of a good comp title is a promising sales history, it is likely that comp titles and BookScan data work together to reinforce conservative white hegemony in the industry

For all of its extensive influence, most of us outside the publishing industry know surprisingly little about BookScan data: how much it costs, what it looks like, or what exactly it includes and measures. According to a 2009 business study,3 publishing house licenses for BookScan data cost somewhere between $350,000 and $750,000 a year at that time. Literary agents, scouts, and other publishing professionals can subscribe to NPD Publishers Marketplace for the humbler baseline price of $2,500 a year, and many authors can view their own BookScan data for free via Amazon.

But academics and almost everyone else are out of luck. When I inquired about getting access to BookScan data directly through NPD Group (the market research company that bought US BookScan from Nielsen in 2017), a sales specialist told me: “There are some limitations to who we are permitted to license our BookScan data to. This includes publishers, retailers, book distributors, publishing arms of universities, university presses and author agents. Do you fall within one of these categories?” When I reached out to NPD Publishers Marketplace, they told me the same thing. David Walter, executive director of NPD Books, confirmed that NPD does not license data to academic researchers: “We only license to publishers and related businesses, and … our license terms preclude sharing of any data publicly, which conflicts with the need to publish academic research. That is why we do not license data for the purposes of academic research.”

This prohibitive policy seems to be a reversal of a previous, more open stance toward academic research, since scholars have indeed used and written about BookScan data in the past.4 Walter declined to comment on this about-face, but the change of heart is certainly disheartening.

While it’s not completely clear why BookScan changed their minds about academic research, it is clear that BookScan numbers, despite their significance and hold on the marketplace, are not completely accurate. BookScan claims to capture 85 percent of physical book purchases from retailers (including Amazon, Walmart, Target, and independent bookstores) and 80 percent of top ebook sales. Even so, there’s a lot that it doesn’t capture: direct-to-consumer sales (which account for most of Belt Publishing’s sales), as well as books sold at events or conferences, books sold by some specialty retailers, and books sold to libraries. BookScan numbers aren’t just conservative, then, but incomplete.

To what extent might BookScan data—with all of these holes and inaccuracies—be shutting out imaginative and experimental literature? To what extent might BookScan data be shutting out writers of color—or anyone, for that matter, who doesn’t resemble the financially successful authors who came before them?

To fully answer these questions, we would need not only BookScan data but other kinds of data, like the race and gender of authors. Until recently, this kind of demographic data did not exist in any comprehensive way.

This is why Richard So and his research team set out to collect data of their own. They began by identifying more than 8,000 widely read books published by the Big Five houses between 1950 and 2018, and then they carefully researched each of the authors and tried to identify their race and ethnicity. As So and his collaborator explained in a 2020 New York Times piece, “to identify those authors’ races and ethnicities, we worked alongside three research assistants, reading through biographies, interviews and social media posts. Each author was reviewed independently by two researchers. If the team couldn’t come to an agreement about an author’s race, or there simply wasn’t enough information to feel confident, we omitted those authors’ books from our analysis.” After this time-consuming curation process, So was able to demonstrate that 95 percent of the identified authors who published during this 70-year time period were white, a finding that quickly went viral on Twitter. Of course many people already knew that the publishing industry was racist, but these data-driven results seemingly struck a chord on social media because they revealed the patterns in aggregate. While So’s valuable, hand-curated demographic data is currently embargoed, it will eventually be published through the Post45 Data Collective,5 which means that it will be available to anyone and mergeable with other kinds of open data, such as library checkout data from the Seattle Public Library.

Since 2017, the SPL has publicly released data about how many times monthly each of its books has been borrowed (from 2005 to the present), as well as whether the book was checked out as a print book, ebook, or audiobook. Importantly, all individual SPL patron information is scrubbed and de-identified.

For this unique dataset, we owe thanks primarily to two people: David Christensen, lead data analyst at the SPL, and Barack Obama. In 2013, President Obama signed an executive order that all federal government data had to be made open, and soon many state and local governments followed suit—including, in 2016, the City of Seattle, which required all of its departments to contribute to the city’s open data program. While many public libraries participate in similar open data programs, most contribute only minimal amounts of data, such as the total number of checkouts from a branch over an entire year. Most libraries don’t have the staff or resources to share anything more substantial. Most also don’t have Christensen, the SPL’s “open data champion,” who advocated for sharing as much data as safely possible.

Safety—more specifically, privacy—is another reason that most libraries don’t share this kind of data: because they have long-held traditions of doggedly protecting patron privacy, making them reticent to collect and release swaths of circulation-related information on the internet. Twenty years ago, for example, the Seattle Public Library was not collecting any checkout data about individual books or patrons. (I had to clarify this point with Christensen. Wait, like, nothing? The Seattle Public Library wasn’t collecting any data about titles or patrons at all? Yep, nothing.)

If you’ve been paying attention to the dates here, you might be wondering: If the SPL only started collecting data in 2017, how do they have borrowing data that stretches back to 2005? It’s a good question. It turns out that while the SPL system itself was not collecting any data between 2005 and 2017, somebody else was, and that somebody was storing the data in an unlikely place within the library itself: in an art installation that hangs above the information desk on the fifth floor. This installation, “Making Visible the Invisible,” was created in 2005 by artist and professor George Legrady, and it features six LCD screens that display real-time data visualizations about the books being checked out and returned from the library.6 Somewhat miraculously, the SPL was able to mine this art installation to recover 10 years of missing, retroactive checkout data.

he many ways that SPL checkout data might be used to understand readers or literary trends are still relatively unexplored. In 2019, The Pudding constructed a silly “Hipster Summer Reading List” based on SPL data, highlighting books that hadn’t been checked from the SPL in over a decade (a perversely funny list but definitely a terrible poolside reading list).

This checkout data is also used internally for a variety of purposes, including to make acquisition decisions, as SPL selection services librarian Frank Brasile explained. But the factor that apparently influences library acquisitions the most is simply what the Big Five choose to publish. “We don’t create content,” Brasile reminded me in a somewhat resigned tone. “We buy content.” To a large extent, then, public libraries inherit the pervasive, problematic whiteness that is endemic in the publishing industry.

Corporate distributors for public libraries are, in fact, already swooping in and capitalizing on the need for data-driven diversity audits. Last year, Ingram launched inClusive—“a one-time assessment service to help Public Libraries diversify their collections by discovering missing titles and underrepresented voices”—while Baker & Taylor and OverDrive unveiled their own diversity analysis tools.7 When I spoke with Brasile, the SPL was partway through one such diversity audit and about to begin another.

The emergence of these audits—almost certainly expensive and with dubious understandings of diversity—makes the significance of open book data even more stark. If we could combine So’s author demographic data with library catalog data, for example, then librarians, academics, journalists, and community members might be able to participate more fully in these audits and conversations, too—and without paying additional, imperfect gatekeepers for the privilege.

Making data publicly available is only the first step, of course. Making meaning from the data is the much harder next leap. What, if anything, can we actually learn about culture by studying data? What kinds of questions can we actually answer?

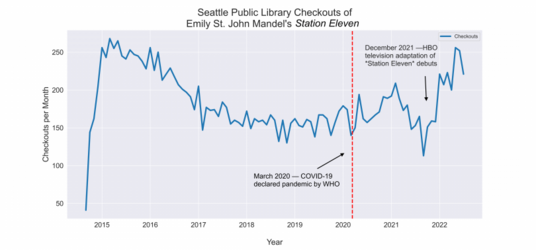

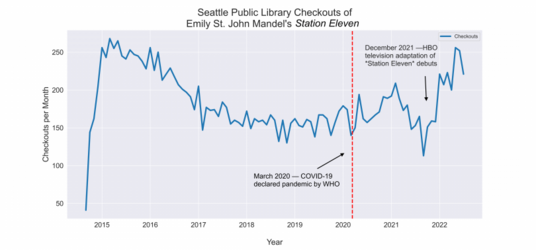

For a start, we can begin to answer some of the questions that I posed at the outset about whether people were clinging to or fleeing from pandemic stories in the early days of COVID-19. If we use open SPL circulation data in lieu of proprietary book sales data, we can see that Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven was not as popular in the first days of the pandemic as it was when it debuted (though it almost reached its record borrowing peak this May, perhaps aided by the HBO television adaptation of the novel that aired earlier this year). We also need to consider the fact that SPL branches physically closed their doors in March 2020. Ebook and audiobook checkouts of Station Eleven both reached all-time highs post–COVID-19.

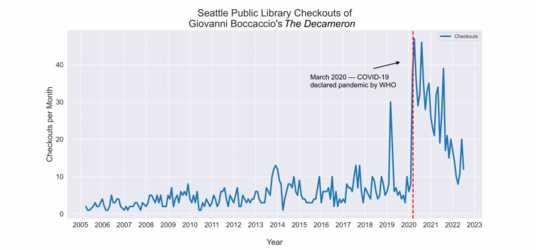

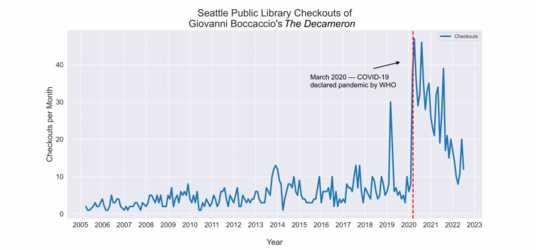

And though Boccaccio’s The Decameron has been less popular than Station Eleven overall, it saw an even more dramatic rise in circulation after March 2020.

So in the wake of COVID-19, it seems that Seattle library patrons have indeed been seeking out pandemic tales. In fact, thanks to the data, that’s something we can track at the level of the individual title and month.

The rest of the essays in this series offer even more compelling testaments to the insights that can be gleaned from cultural data. Drawing on a year of audiobook data from the Swedish platform Storytel, Karl Berglund takes us on a deep dive into the idiosyncratic listening habits of specific (anonymized) users. In so doing, Berglund maps out three distinct kinds of reader-listeners, including the kind of listener—a “repeater”—who consumes Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo trilogy every day, over and over again.

These audiobook “life soundtracks,” as Berglund refers to them, are somewhat akin to Spotify’s mood-driven “vibes” playlists, a musical innovation examined by Tom McEnaney and Kaitlyn Todd through the playlists’ acoustic and demographic metadata. What the researchers find is that these new “vibes” playlists feature younger, more diverse artists than traditional genre playlists like country or hip-hop, but they are also quieter and sadder (“soundtracks to subdue,” as the authors put it).

While McEnaney and Todd call our attention to the manipulative maneuvers behind Spotify’s algorithms, Jordan Pruett explores the artifices behind the New York Times’ famous bestseller list (an investigation that pairs well with the NYT bestseller data that he curated and published in the Post45 Data Collective). Pruett lays bare how the seemingly authoritative list has long been shaped by distinct historical circumstances and editorial choices.

The last three essays all tackle important issues of cultural representation by turning to numbers. Howard Rambsy and Kenton Rambsy examine how, and how often, the New York Times discusses Black writers. They offer quantitative proof of the frequently leveled critique that elite white publishing outlets often cover only one Black writer at a time, and they show that this is especially true with writers like James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, and Colson Whitehead.

Nora Shaalan explores the fiction section of the New Yorker, especially the view of the world imagined by its short stories over the past 70 years. Despite pretensions toward cosmopolitanism, the magazine, Shaalan reports, largely publishes short stories that are provincial, both domestically and globally.

Finally, Cody Mejeur and Xavier Ho chart the history of gender and sexuality representation in video games, both in terms of who is portrayed in games and who makes them. Today, the common line is that games have become more inclusive. But, as Mejeur and Ho reveal, whatever inclusiveness does exist is driven by indie producers on the margins—and there’s considerable obstacles still to overcome.

The essays of Hacking the Culture Industries, when considered together, demonstrate that the future of human culture is already being determined by data. They also show that to understand this future and to have a chance at reshaping it, we need to care about data. We need to know where all the important cultural data is, who controls it, and how it’s being used.

We also need to create, share, and combine counterdata of our own, not just to understand what’s going on with contemporary culture, but also to fight back against the powers that threaten it. Big corporate data is currently poised to make literature and culture more unequal, more restrictive, and more conservative. To reverse the tides—to make culture more equitable, more inclusive, and more imaginative—we may need to start by hacking the culture industries.

This article was commissioned by Laura McGrath, Dan Sinykin, and Richard Jean So. icon

C. Clayton Childress, “Decision-Making, Market Logic and the Rating Mindset: Negotiating BookScan in the Field of US Trade Publishing,” European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 15, no. 5 (October 2012): 613. ↩

“I need to create a coherent story, so if the numbers help tell that story I say ‘You know, BookScan says this,’ but if the BookScan numbers don’t help me tell my story, I say ‘You know, BookScan says this, but it only captures 75 percent of the market, so we should focus on this other thing.’” Childress, “Decision-Making, Market Logic and the Rating Mindset,” 615. ↩

Kurt Andrews and Philip M. Napoli, “Changing Market Information Regimes: A Case Study of the Transition to the BookScan Audience Measurement System in the U.S. Book Publishing Industry,” Journal of Media Economics, vol. 19, no. 1 (January 2006), 44. ↩

See Jonah Berger, Alan T. Sorensen, and Scott J. Rasmussen, “Positive Effects of Negative Publicity: When Negative Reviews Increase Sales,” Marketing Science, vol. 29, no. 5 (2010); and Xindi Wang, Burcu Yucesoy, Onur Varol, Tina Eliassi-Rad, and Albert-László Barabási, “Success in Books: Predicting Book Sales before Publication,” EPJ Data Science, vol. 8, no. 31 (2019). ↩

The data hasn’t been published yet because it was integral to Richard So’s book Redlining Culture (Columbia University Press, 2020), and it is also at the core of The Conglomerate Era, a forthcoming book by Dan Sinykin. When Sinykin’s book is published, they plan to release the data to the Post45 Data Collective. ↩

According to the installation’s production lead, Rama Holtzein, it may be “the longest running media arts project which has been continuously collecting data.” ↩

Baker & Taylor’s “diversity analysis” tool, collectionHQ can “analyz(e) your library’s Fiction and Non-Fiction collections against industry accepted DEI topics” and “evaluate(e) representation of diverse populations in both print and digital collections.” OverDrive’s diversity audit tools include the still in-development Readtelligence—“an upcoming suite of tools for ebook selection and curation developed by the company using artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning tools to analyze every ebook in the OverDrive Marketplace.”

And for a supposed Data Scientist the author of this ignores the big problem with public library borrows: Namely if the book isn't on the shelf nobody can borrow it. As in the Boston Public Library's Overdrive site has 20 ebooks (plus a listing for a forward he wrote) and 2 audiobooks by John Scalzi for borrowing and 1 ebook and no audiobooks by Larry Correia. Whether this is due to Tor pushing for libraries more or librarians being biased in favor of Scalzi over Correia, who can say? Maybe Scalzi just sells better, but better by a factor of twenty? In any event, any data from the Boston Public Library would make Scalzi look pretty good and Correia like a nobody.

Anyhoo, enjoy.

WHERE IS ALL THE BOOK DATA? / https://archive.ph/ESCu6

10.4.2022

DIGITAL HUMANITIES

Y MELANIE WALSH

Culture industries increasingly use our data to sell us their products. It’s time to use their data to study them. To that end, we created the Post45 Data Collective, an open access site that peer reviews and publishes literary and cultural data. This a partnership between the Data Collective and Public Books, a series called Hacking the Culture Industries, brings you data-driven essays that change how we understand audiobooks, bestselling books, streaming music, video games, influential literary institutions such as the New York Times and the New Yorker, and more. Together, they show a new way of understanding how culture is made, and how we can make it better.

—Laura McGrath and Dan Sinykin

BY MELANIE WALSH

Culture industries increasingly use our data to sell us their products. It’s time to use their data to study them. To that end, we created the Post45 Data Collective, an open access site that peer reviews and publishes literary and cultural data. This a partnership between the Data Collective and Public Books, a series called Hacking the Culture Industries, brings you data-driven essays that change how we understand audiobooks, bestselling books, streaming music, video games, influential literary institutions such as the New York Times and the New Yorker, and more. Together, they show a new way of understanding how culture is made, and how we can make it better.

—Laura McGrath and Dan Sinykin

After the first lockdown in March 2020, I went looking for book sales data. I’m a data scientist and a literary scholar, and I wanted to know what books people were turning to in the early days of the pandemic for comfort, distraction, hope, guidance. How many copies of Emily St. John Mandel’s pandemic novel Station Eleven were being sold in COVID-19 times compared to when the novel debuted in 2014? And what about Giovanni Boccaccio’s much older—14th-century—plague stories, The Decameron? Were people clinging to or fleeing from pandemic tales during peak coronavirus panic? You might think, as I naively did, that a researcher would be able to find out exactly how many copies of a book were sold in certain months or years. But you, like me, would be wrong.

I went looking for book sales data, only to find that most of it is proprietary and purposefully locked away. What I learned was that the single most influential data in the publishing industry—which, every day, determines book contracts and authors’ lives—is basically inaccessible to anyone beyond the industry. And I learned that this is a big problem.

The problem with book sales data may not, at first, be apparent. Every week, the New York Times of course releases its famous list of “bestselling” books, but this list does not include individual sales numbers. Moreover, select book sales figures are often reported to journalists—like the fact that Station Eleven has sold more than 1.5 million copies overall—and also shared through outlets like Publishers Weekly. However, the underlying source for all these sales figures is typically an exclusive subscription service called BookScan: the most granular, comprehensive, and influential book sales data in the industry (though it still has significant holes—more on that to come).

Since its launch in 2001, BookScan has grown in authority. All the major publishing houses now rely on BookScan data, as do many other publishing professionals and authors. But, as I found to my surprise, pretty much everybody else is explicitly banned from using BookScan data, including academics. The toxic combination of this data’s power in the industry and its secretive inaccessibility to those beyond the industry reveals a broader problem. If we want to understand the contemporary literary world, we need better book data. And we need this data to be free, open, and interoperable.

Fortunately, there are a number of forward-thinking people who are already leading the charge for open book data. The Seattle Public Library is one of the few libraries in the country that releases (anonymized) book checkout data online, enabling anyone to download it from the internet for free. It isn’t book sales data, but it’s close. And such data might help us understand how the popularity of certain books fluctuates over time and in response to historical events like the COVID-19 pandemic (especially if more libraries around the country join the open data effort). Literary scholars have also begun to compile “counterdata” about the publishing industry. Richard So, a professor of English and cultural analytics at McGill University, and Laura McGrath, an English professor at Temple University, have respectively collected data about the race and ethnicity of authors published by mainstream publishing houses. Through their work, So and McGrath each prove that the Big Five houses have historically been dominated by white authors and that they continue to systematically reinforce whiteness today.

While all of this data is powerful in its own right, it becomes even more powerful if we can combine it all together: if we can merge author demographic data with library checkout data or with other literary trends. This promise anchors the Post45 Data Collective, an open-access repository for literary and cultural data that was founded by McGrath and Emory professor Dan Sinykin, and that I now lead as a coeditor with Sinykin. One of the goals of the repository is to help researchers get credit for the data that they painstakingly collect, clean, and share. But a broader goal is to share free cultural data with anybody who wants to reuse and recombine it to better understand contemporary literature, music, art, and more.

Now, I am pleased to introduce a Public Books series that honors and revolves around the Post45 Data Collective, and that will hopefully add to it and strengthen it. This series, Hacking the Culture Industries, demonstrates how corporate algorithms and data are shaping contemporary culture; but it also reveals how the same tools, in different hands, can be used to study, understand, and critique culture and its corporate influences in turn. Each of the authors in this series takes on a different kind of cultural data—from New Yorker short stories to Spotify music trends, from New York Times reviews to audiobook listening patterns. (Some of the data featured in these essays will also be published in, or is already available through, the Post45 Data Collective, enabling further research and exploration.)

I will say more about this series below, but first I want to focus on the broader significance of the Post45 Data Collective’s mission: to make book data (and other kinds of cultural data) free and open to the public.

To people who care about literature, data is often seen as a neoliberal bogeyman, the very antithesis of literature and possibly even what’s ruining literature. Plus, people tend to think that data is boring. To be fair, data is sometimes a neoliberal bogeyman, it is sometimes boring, and it may in fact be making literature more boring (more on that to come, too). But that’s precisely why we need to pay attention to it.

Corporate data already deeply influences the contemporary literary world, as revealed both here and in the broader essay series. And so, if you care about books, you should probably care about book data.

BookScan’s influence in the publishing world is clear and far-reaching. To an editor, BookScan numbers offer two crucial data points: (1) the sales history of the potential author, if it exists, and (2) the sales history of comparable, or “comp,” titles. These data points, if deemed unfavorable, can mean a book is dead in the water.

Take it from freelance editor Christina Boys, whom I spoke with over email, and who worked for 20 years as an editor at two of the Big Five publishing houses (Simon & Schuster and Hachette Book Group). Boys told me that BookScan data is “very important” for deciding whether to acquire or pass on a book; BookScan is also used to determine the size of an advance, to dictate the scale of a marketing campaign or book tour, and to help sell subsidiary rights like translation rights or book club rights. “A poor sales history on BookScan often results in an immediate pass,” Boys said.

Clayton Childress, a sociologist at the University of Toronto, came to similar conclusions in his 2012 study of BookScan data, in which he interviewed and observed more than 40 acquisition editors from across the country. Bad book sales numbers can haunt an author “like a bad credit score,” Childress reported, and they can “caus[e] others to be hesitant to do business with them because of past failures.”1

According to editors like Boys, the sway of book sales figures has siphoned much of the creativity and originality out of contemporary book publishing. “There’s less opportunity to acquire or promote a book based on things like gut instinct, quality of the writing, uniqueness of an idea, or literary or societal merit,” Boys claimed. “While passion—arguing that a book should be published—still matters, using that as a justification when it’s contrary to BookScan data has become increasingly challenging.” In a similar vein, Anne Trubek, the founder and publisher of the independent press Belt Publishing, told me that BookScan data is a strong conservative force in the industry—one of the reasons, though not the only reason, that Belt Publishing stopped subscribing after only one year. Trubek says that BookScan data encourages publishers to keep recycling the same kinds of books that sold well in the past. “I didn’t want to be a publisher who was working that way,” she elaborated. “That was not interesting. I think a lot of Big Five publishing is driven by data, and I think that things end up much more unimaginative as a result.”

Despite these claims, other publishing professionals maintain that BookScan data has not changed their work quite as dramatically. Childress interviewed one editor who explained that he manages to use BookScan data in creative ways to support his own independent choices.2 Yet even when editors find inventive ways to use BookScan data and to preserve their own aesthetic judgment, it is striking that they must still use and reckon with BookScan data in some form.

Perhaps most importantly, however, it is likely that books end up much more racially homogenous—that is, white—as a result of BookScan data, too. For example, in McGrath’s pioneering research on “comp” titles (the books that agents and editors claim are “comparable” to a pitched book), she found that 96 percent of the most frequently used comps were written by white authors. Because one of the most important features of a good comp title is a promising sales history, it is likely that comp titles and BookScan data work together to reinforce conservative white hegemony in the industry

For all of its extensive influence, most of us outside the publishing industry know surprisingly little about BookScan data: how much it costs, what it looks like, or what exactly it includes and measures. According to a 2009 business study,3 publishing house licenses for BookScan data cost somewhere between $350,000 and $750,000 a year at that time. Literary agents, scouts, and other publishing professionals can subscribe to NPD Publishers Marketplace for the humbler baseline price of $2,500 a year, and many authors can view their own BookScan data for free via Amazon.

But academics and almost everyone else are out of luck. When I inquired about getting access to BookScan data directly through NPD Group (the market research company that bought US BookScan from Nielsen in 2017), a sales specialist told me: “There are some limitations to who we are permitted to license our BookScan data to. This includes publishers, retailers, book distributors, publishing arms of universities, university presses and author agents. Do you fall within one of these categories?” When I reached out to NPD Publishers Marketplace, they told me the same thing. David Walter, executive director of NPD Books, confirmed that NPD does not license data to academic researchers: “We only license to publishers and related businesses, and … our license terms preclude sharing of any data publicly, which conflicts with the need to publish academic research. That is why we do not license data for the purposes of academic research.”

This prohibitive policy seems to be a reversal of a previous, more open stance toward academic research, since scholars have indeed used and written about BookScan data in the past.4 Walter declined to comment on this about-face, but the change of heart is certainly disheartening.

While it’s not completely clear why BookScan changed their minds about academic research, it is clear that BookScan numbers, despite their significance and hold on the marketplace, are not completely accurate. BookScan claims to capture 85 percent of physical book purchases from retailers (including Amazon, Walmart, Target, and independent bookstores) and 80 percent of top ebook sales. Even so, there’s a lot that it doesn’t capture: direct-to-consumer sales (which account for most of Belt Publishing’s sales), as well as books sold at events or conferences, books sold by some specialty retailers, and books sold to libraries. BookScan numbers aren’t just conservative, then, but incomplete.

To what extent might BookScan data—with all of these holes and inaccuracies—be shutting out imaginative and experimental literature? To what extent might BookScan data be shutting out writers of color—or anyone, for that matter, who doesn’t resemble the financially successful authors who came before them?

To fully answer these questions, we would need not only BookScan data but other kinds of data, like the race and gender of authors. Until recently, this kind of demographic data did not exist in any comprehensive way.

This is why Richard So and his research team set out to collect data of their own. They began by identifying more than 8,000 widely read books published by the Big Five houses between 1950 and 2018, and then they carefully researched each of the authors and tried to identify their race and ethnicity. As So and his collaborator explained in a 2020 New York Times piece, “to identify those authors’ races and ethnicities, we worked alongside three research assistants, reading through biographies, interviews and social media posts. Each author was reviewed independently by two researchers. If the team couldn’t come to an agreement about an author’s race, or there simply wasn’t enough information to feel confident, we omitted those authors’ books from our analysis.” After this time-consuming curation process, So was able to demonstrate that 95 percent of the identified authors who published during this 70-year time period were white, a finding that quickly went viral on Twitter. Of course many people already knew that the publishing industry was racist, but these data-driven results seemingly struck a chord on social media because they revealed the patterns in aggregate. While So’s valuable, hand-curated demographic data is currently embargoed, it will eventually be published through the Post45 Data Collective,5 which means that it will be available to anyone and mergeable with other kinds of open data, such as library checkout data from the Seattle Public Library.

Since 2017, the SPL has publicly released data about how many times monthly each of its books has been borrowed (from 2005 to the present), as well as whether the book was checked out as a print book, ebook, or audiobook. Importantly, all individual SPL patron information is scrubbed and de-identified.

For this unique dataset, we owe thanks primarily to two people: David Christensen, lead data analyst at the SPL, and Barack Obama. In 2013, President Obama signed an executive order that all federal government data had to be made open, and soon many state and local governments followed suit—including, in 2016, the City of Seattle, which required all of its departments to contribute to the city’s open data program. While many public libraries participate in similar open data programs, most contribute only minimal amounts of data, such as the total number of checkouts from a branch over an entire year. Most libraries don’t have the staff or resources to share anything more substantial. Most also don’t have Christensen, the SPL’s “open data champion,” who advocated for sharing as much data as safely possible.

Safety—more specifically, privacy—is another reason that most libraries don’t share this kind of data: because they have long-held traditions of doggedly protecting patron privacy, making them reticent to collect and release swaths of circulation-related information on the internet. Twenty years ago, for example, the Seattle Public Library was not collecting any checkout data about individual books or patrons. (I had to clarify this point with Christensen. Wait, like, nothing? The Seattle Public Library wasn’t collecting any data about titles or patrons at all? Yep, nothing.)

If you’ve been paying attention to the dates here, you might be wondering: If the SPL only started collecting data in 2017, how do they have borrowing data that stretches back to 2005? It’s a good question. It turns out that while the SPL system itself was not collecting any data between 2005 and 2017, somebody else was, and that somebody was storing the data in an unlikely place within the library itself: in an art installation that hangs above the information desk on the fifth floor. This installation, “Making Visible the Invisible,” was created in 2005 by artist and professor George Legrady, and it features six LCD screens that display real-time data visualizations about the books being checked out and returned from the library.6 Somewhat miraculously, the SPL was able to mine this art installation to recover 10 years of missing, retroactive checkout data.

he many ways that SPL checkout data might be used to understand readers or literary trends are still relatively unexplored. In 2019, The Pudding constructed a silly “Hipster Summer Reading List” based on SPL data, highlighting books that hadn’t been checked from the SPL in over a decade (a perversely funny list but definitely a terrible poolside reading list).

This checkout data is also used internally for a variety of purposes, including to make acquisition decisions, as SPL selection services librarian Frank Brasile explained. But the factor that apparently influences library acquisitions the most is simply what the Big Five choose to publish. “We don’t create content,” Brasile reminded me in a somewhat resigned tone. “We buy content.” To a large extent, then, public libraries inherit the pervasive, problematic whiteness that is endemic in the publishing industry.

Corporate distributors for public libraries are, in fact, already swooping in and capitalizing on the need for data-driven diversity audits. Last year, Ingram launched inClusive—“a one-time assessment service to help Public Libraries diversify their collections by discovering missing titles and underrepresented voices”—while Baker & Taylor and OverDrive unveiled their own diversity analysis tools.7 When I spoke with Brasile, the SPL was partway through one such diversity audit and about to begin another.

The emergence of these audits—almost certainly expensive and with dubious understandings of diversity—makes the significance of open book data even more stark. If we could combine So’s author demographic data with library catalog data, for example, then librarians, academics, journalists, and community members might be able to participate more fully in these audits and conversations, too—and without paying additional, imperfect gatekeepers for the privilege.

Making data publicly available is only the first step, of course. Making meaning from the data is the much harder next leap. What, if anything, can we actually learn about culture by studying data? What kinds of questions can we actually answer?

For a start, we can begin to answer some of the questions that I posed at the outset about whether people were clinging to or fleeing from pandemic stories in the early days of COVID-19. If we use open SPL circulation data in lieu of proprietary book sales data, we can see that Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven was not as popular in the first days of the pandemic as it was when it debuted (though it almost reached its record borrowing peak this May, perhaps aided by the HBO television adaptation of the novel that aired earlier this year). We also need to consider the fact that SPL branches physically closed their doors in March 2020. Ebook and audiobook checkouts of Station Eleven both reached all-time highs post–COVID-19.

And though Boccaccio’s The Decameron has been less popular than Station Eleven overall, it saw an even more dramatic rise in circulation after March 2020.

So in the wake of COVID-19, it seems that Seattle library patrons have indeed been seeking out pandemic tales. In fact, thanks to the data, that’s something we can track at the level of the individual title and month.

The rest of the essays in this series offer even more compelling testaments to the insights that can be gleaned from cultural data. Drawing on a year of audiobook data from the Swedish platform Storytel, Karl Berglund takes us on a deep dive into the idiosyncratic listening habits of specific (anonymized) users. In so doing, Berglund maps out three distinct kinds of reader-listeners, including the kind of listener—a “repeater”—who consumes Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo trilogy every day, over and over again.

These audiobook “life soundtracks,” as Berglund refers to them, are somewhat akin to Spotify’s mood-driven “vibes” playlists, a musical innovation examined by Tom McEnaney and Kaitlyn Todd through the playlists’ acoustic and demographic metadata. What the researchers find is that these new “vibes” playlists feature younger, more diverse artists than traditional genre playlists like country or hip-hop, but they are also quieter and sadder (“soundtracks to subdue,” as the authors put it).

While McEnaney and Todd call our attention to the manipulative maneuvers behind Spotify’s algorithms, Jordan Pruett explores the artifices behind the New York Times’ famous bestseller list (an investigation that pairs well with the NYT bestseller data that he curated and published in the Post45 Data Collective). Pruett lays bare how the seemingly authoritative list has long been shaped by distinct historical circumstances and editorial choices.

The last three essays all tackle important issues of cultural representation by turning to numbers. Howard Rambsy and Kenton Rambsy examine how, and how often, the New York Times discusses Black writers. They offer quantitative proof of the frequently leveled critique that elite white publishing outlets often cover only one Black writer at a time, and they show that this is especially true with writers like James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, and Colson Whitehead.

Nora Shaalan explores the fiction section of the New Yorker, especially the view of the world imagined by its short stories over the past 70 years. Despite pretensions toward cosmopolitanism, the magazine, Shaalan reports, largely publishes short stories that are provincial, both domestically and globally.

Finally, Cody Mejeur and Xavier Ho chart the history of gender and sexuality representation in video games, both in terms of who is portrayed in games and who makes them. Today, the common line is that games have become more inclusive. But, as Mejeur and Ho reveal, whatever inclusiveness does exist is driven by indie producers on the margins—and there’s considerable obstacles still to overcome.

The essays of Hacking the Culture Industries, when considered together, demonstrate that the future of human culture is already being determined by data. They also show that to understand this future and to have a chance at reshaping it, we need to care about data. We need to know where all the important cultural data is, who controls it, and how it’s being used.

We also need to create, share, and combine counterdata of our own, not just to understand what’s going on with contemporary culture, but also to fight back against the powers that threaten it. Big corporate data is currently poised to make literature and culture more unequal, more restrictive, and more conservative. To reverse the tides—to make culture more equitable, more inclusive, and more imaginative—we may need to start by hacking the culture industries.

This article was commissioned by Laura McGrath, Dan Sinykin, and Richard Jean So. icon

C. Clayton Childress, “Decision-Making, Market Logic and the Rating Mindset: Negotiating BookScan in the Field of US Trade Publishing,” European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 15, no. 5 (October 2012): 613. ↩

“I need to create a coherent story, so if the numbers help tell that story I say ‘You know, BookScan says this,’ but if the BookScan numbers don’t help me tell my story, I say ‘You know, BookScan says this, but it only captures 75 percent of the market, so we should focus on this other thing.’” Childress, “Decision-Making, Market Logic and the Rating Mindset,” 615. ↩

Kurt Andrews and Philip M. Napoli, “Changing Market Information Regimes: A Case Study of the Transition to the BookScan Audience Measurement System in the U.S. Book Publishing Industry,” Journal of Media Economics, vol. 19, no. 1 (January 2006), 44. ↩

See Jonah Berger, Alan T. Sorensen, and Scott J. Rasmussen, “Positive Effects of Negative Publicity: When Negative Reviews Increase Sales,” Marketing Science, vol. 29, no. 5 (2010); and Xindi Wang, Burcu Yucesoy, Onur Varol, Tina Eliassi-Rad, and Albert-László Barabási, “Success in Books: Predicting Book Sales before Publication,” EPJ Data Science, vol. 8, no. 31 (2019). ↩

The data hasn’t been published yet because it was integral to Richard So’s book Redlining Culture (Columbia University Press, 2020), and it is also at the core of The Conglomerate Era, a forthcoming book by Dan Sinykin. When Sinykin’s book is published, they plan to release the data to the Post45 Data Collective. ↩

According to the installation’s production lead, Rama Holtzein, it may be “the longest running media arts project which has been continuously collecting data.” ↩

Baker & Taylor’s “diversity analysis” tool, collectionHQ can “analyz(e) your library’s Fiction and Non-Fiction collections against industry accepted DEI topics” and “evaluate(e) representation of diverse populations in both print and digital collections.” OverDrive’s diversity audit tools include the still in-development Readtelligence—“an upcoming suite of tools for ebook selection and curation developed by the company using artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning tools to analyze every ebook in the OverDrive Marketplace.”

- Joined

- Sep 25, 2021

Re: No Larry C Books in the Boston Library digital area

I googled around because Baen (LC's publisher) has some weird rights issues, and it looks like their Audiobooks were being distributed to the Boston Library by RBDigital and RBMedia, which closed shop in 2021, therefore memory-holing several hundred titles.

Unless Baen finds another Audio distributor, they'll only be available through the publisher's free library, and not a public library.

And for a supposed Data Scientist the author of this ignores the big problem with public library borrows: Namely if the book isn't on the shelf nobody can borrow it. As in the Boston Public Library's Overdrive site has 20 ebooks (plus a listing for a forward he wrote) and 2 audiobooks by John Scalzi for borrowing and 1 ebook and no audiobooks by Larry Correia. Whether this is due to Tor pushing for libraries more or librarians being biased in favor of Scalzi over Correia, who can say? Maybe Scalzi just sells better, but better by a factor of twenty? In any event, any data from the Boston Public Library would make Scalzi look pretty good and Correia like a nobody.

I googled around because Baen (LC's publisher) has some weird rights issues, and it looks like their Audiobooks were being distributed to the Boston Library by RBDigital and RBMedia, which closed shop in 2021, therefore memory-holing several hundred titles.

Unless Baen finds another Audio distributor, they'll only be available through the publisher's free library, and not a public library.

- Joined

- Sep 26, 2020

Ugh. As a boring fantasy reader and longtime thread lurker DATA SCIENCE != HITTING LINE GRAPH BUTTON IN EXCEL FFS THIS IS THE REASON I HAVE TO CALL MY SELF ML DEV-OPS I HATE ITTTT!!#£&£@! FUCK WHOEVER INVENTED THE 1YR MARTHTERS IN DATA THIENTHE FUCK OFF AND DO A LIBRARY SCIENCE QUAL AND DIE YOUR HAIR BLUE YOU STUPID BITCHES

Also Patrick Rofthuss sucks and in my house we call it The Name of the Farts and he looks fat and I would not have sex with him.

And Scalzi is a weak hack Jack Vance 4evA <3

Also Patrick Rofthuss sucks and in my house we call it The Name of the Farts and he looks fat and I would not have sex with him.

And Scalzi is a weak hack Jack Vance 4evA <3

Last edited:

- Joined

- Oct 5, 2018

Man, this thread has been a SUPER fun thread to read through, thank you so much to all the industry insiders (both on the writing and publishing sides) giving their input because it's fascinating to know what's going on.

It's funny (and depressing) hearing about how the cost of high-end classic cover art is one of the driving factors of the increasingly bland covers on display.

An interesting consideration is that technically speaking, it's harder than ever to make a good living as a cover artist; not because they're in less demand, but because of a lot of other factors. The pricing scale for commercial illustration has apparently been stagnant for decades, and the fact that there's only a handful of big publishing houses means that if you burn a bridge, it's a hell of a lot more of a problem so artists are a lot less likely to stick up for their rights or principles.

I learned under a Big Name Artist who works in illustration (idk if he's Michael Whelan tier, but they're probably friends sort of level), book cover illustration among other things. He still enjoys what he does and wins lots of awards and gets PLENTY of work but he says things have really changed a lot over the decades and it's not been for the better. It's not a great time to be a cover artist if even the rockstar illustrators are feeling it.

It's funny (and depressing) hearing about how the cost of high-end classic cover art is one of the driving factors of the increasingly bland covers on display.

An interesting consideration is that technically speaking, it's harder than ever to make a good living as a cover artist; not because they're in less demand, but because of a lot of other factors. The pricing scale for commercial illustration has apparently been stagnant for decades, and the fact that there's only a handful of big publishing houses means that if you burn a bridge, it's a hell of a lot more of a problem so artists are a lot less likely to stick up for their rights or principles.

I learned under a Big Name Artist who works in illustration (idk if he's Michael Whelan tier, but they're probably friends sort of level), book cover illustration among other things. He still enjoys what he does and wins lots of awards and gets PLENTY of work but he says things have really changed a lot over the decades and it's not been for the better. It's not a great time to be a cover artist if even the rockstar illustrators are feeling it.

BetterFuckChuck

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Jul 8, 2022

- Joined

- Oct 5, 2018

On a side note, I know that Tamsyn Muir has come up in this thread before, but the new book in her series recently dropped and I've been dodging that shit everywhere because it looks insufferable. According to people here (from what I recall) the story itself is actually way less uwuwuwuwu lesbeans 24/7 than tumblr portrays it, but.... is it a recent trend to just advertise things purely catering to the lol so random and gay crowd?

I know this series has spectacular cover art by a fellow called Tommy Arnold...

...so why the fuck is the official advertising Tor is pushing shit like this?

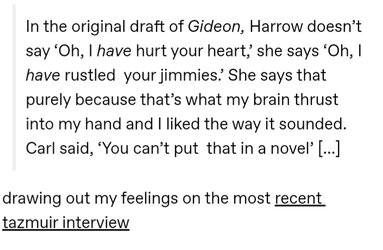

If this is a series about space necromancers and shit, which should be objectively the coolest premise ever, why the fuck is the author using interviews to describe it like this?

Why is it taking an editor stepping in to convince you to take the dated meme out of your not-set-in-our-world theoretically serious book?

I get that she started out as a fanfic author with all the baggage that entails, but Jesus christ so did people like Naomi Novik and you don't end up with a fucking mess like this. From what I gather the recent book is a case of 'split book 3 into book 3 and 4 so we could have the lolrandom trope-heavy interlude before getting back to the plot' but still. Christ almighty.

I want to be proven wrong but idk, would love some hot kiwi takes from anyone who has made their way through these because I'm super not convinced.

I know this series has spectacular cover art by a fellow called Tommy Arnold...

...so why the fuck is the official advertising Tor is pushing shit like this?

If this is a series about space necromancers and shit, which should be objectively the coolest premise ever, why the fuck is the author using interviews to describe it like this?

Why is it taking an editor stepping in to convince you to take the dated meme out of your not-set-in-our-world theoretically serious book?

I get that she started out as a fanfic author with all the baggage that entails, but Jesus christ so did people like Naomi Novik and you don't end up with a fucking mess like this. From what I gather the recent book is a case of 'split book 3 into book 3 and 4 so we could have the lolrandom trope-heavy interlude before getting back to the plot' but still. Christ almighty.

I want to be proven wrong but idk, would love some hot kiwi takes from anyone who has made their way through these because I'm super not convinced.

frap

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Oct 22, 2021

I found the first instalment (Gideon the Ninth?) unreadable. Shame, because the cover art is gorgeous.

I think it was around the time I also attempted This Is How You Lose The Time War, which I found entirely incomprehensible. I concluded the rave reviews that thing got were a real life the-emperor-has-no-clothes situation.

I think it was around the time I also attempted This Is How You Lose The Time War, which I found entirely incomprehensible. I concluded the rave reviews that thing got were a real life the-emperor-has-no-clothes situation.

- Joined

- Mar 17, 2019

tbh you could have written the best book in the world, but if the only description you give for it is "genderqueer anti-TERF meets coffeshop AU meets hyperpolygomous #darkacademia" I am dropping that shit immediately. I am glad there's a little bit of pushback against it from the same spaces these tags are trying to appeal to, but it should be bigger. At what point did it become problematic to just give a tease of what the book's plot is gonna be about?

(I was looking at the comments of one of the TikToks I saw dissing on this trend and I liked someone calling it the "Sarah J. Massification of books". )

(I was looking at the comments of one of the TikToks I saw dissing on this trend and I liked someone calling it the "Sarah J. Massification of books". )

I'm about to go on a rather big tangent, but it's because Naomi Novik started out as a fanfic writer for the Aubrey–Maturin series, which means that she became enamored with a mid XXth century series of 20 and half books that weren’t at all tailored to her demographic, all excessively preoccupied with the daily functioning of Napoleonic wars’ tall ships down to the last broken spar lost in a battle or a gale, and written in a flowery, purposely old-fashioned and slow-paced style. She was of course mainly interested with putting gay sex into the friendship of the two main characters -case in point, the first installment in the Temeraire series started out as a Aubrey–Maturin fanfic she made into a full-length book; the captain was originally Jack Aubrey and the dragon, Stephan Maturin– but her loving the A-M series is at the absolute opposite of the immediate gratification, myopia of interests to only what is immediately relevant and relatable to the self, easy consumption at the expense of complexity or depth and obsession with irony and self-awareness that plagues modern YA readers and writers. Novik also comes from an older generation of internet fandom raised before Tumblr and black-and-white SWJ thinking and muh mental health and spending all your days on SM was a thing and made of more or less autistic but mostly functional adults. Novik wasn't posting about the plight of black trans sex workers and her self-diagnosed CPTSD on Instagram back then, instead she helmed the creation of the Archive of Our Own fanfic archive and coordinated a big fanfic exchange event that is still running today.I get that she started out as a fanfic author with all the baggage that entails, but Jesus christ so did people like Naomi Novik and you don't end up with a fucking mess like this. From what I gather the recent book is a case of 'split book 3 into book 3 and 4 so we could have the lolrandom trope-heavy interlude before getting back to the plot' but still. Christ almighty.

Tamsyn Muir started out as a Homestuck fan which is a series that is despised even by other fanfic writers, and she’s a literal woman child who pretends to be a lesbian because she hanged out with the LGBT club when she was never attracted to women, in her own words, then married a man she doesn’t have sex with and describes their relationship not as a romantic one but some made-up friendship thing from Homestuck, both her idea and not her husband’s, and she never held a job when she doesn’t come from money iirc. She also feels the need to broadcast all those details in her interviews because she sees nothing wrong or pathetic with any of it. Her insight into the human condition must be negative at this point because she’s so immature, and people who are immature are unable to hold nuanced, interesting views of the world and the humans that inhabit it and convey them relatably in their writing even if they have the necessary writing chops because they are narcissistically self-obsessed but not self-aware and rudderless and lacking life experience, like children. (Children have excuses that failure-to-launch adults have not, of course.) So when they write, they have no choice but to use the same tripe tropes emptied of meaning and devoid of sincerity only touted for their relevance to a given demographic, lol-random irony, dull fanservice for their target group and at best sprinkle over some flashy stylistic stuff if they even have the talent for it, all because they have nothing to say of import. That’s the crop of the dysfunctional side of the new generation of internet fandom, the same that is corralled into the YA-no-older-than-highschool demographic when they write because they clearly aren’t adults in their way of thinking, but normal teenagers doesn’t find them all that relatable either, and so we have this YA literature exclusively written by wine aunts for other wine aunts and assorted woman children.

- Joined

- Feb 3, 2013

From that article:

First: it ignores the fact that there were op-eds going around at the time discussing "famous plague literature" like the Decameron and Daniel Defoe's Journal of the Plague Year. The correct analysis should be to graph "Mentions of Boccaccio in popular media" versus library checkouts - many people probably never heard of him before the media mentions. And of course that goes doubly for the forgettable YA trash they're comparing it with.

Second: the Decameron is only "plague literature" in the sense that the Canterbury Tales is a "road trip novel". It's just the framing device to get a bunch of characters together swapping stories. It makes no literary sense to compare it to books like "Station Eleven" or "The Stand".

The Seattle library data they mentioned sounds interesting though - it might be fun to look into what an entire city of lolcows reads. Here's the link: https://data.seattle.gov/Community/Checkouts-by-Title/tmmm-ytt6

This is complete nonsense for two reasons.And though Boccaccio’s The Decameron has been less popular than Station Eleven overall, it saw an even more dramatic rise in circulation after March 2020.

First: it ignores the fact that there were op-eds going around at the time discussing "famous plague literature" like the Decameron and Daniel Defoe's Journal of the Plague Year. The correct analysis should be to graph "Mentions of Boccaccio in popular media" versus library checkouts - many people probably never heard of him before the media mentions. And of course that goes doubly for the forgettable YA trash they're comparing it with.

Second: the Decameron is only "plague literature" in the sense that the Canterbury Tales is a "road trip novel". It's just the framing device to get a bunch of characters together swapping stories. It makes no literary sense to compare it to books like "Station Eleven" or "The Stand".

The Seattle library data they mentioned sounds interesting though - it might be fun to look into what an entire city of lolcows reads. Here's the link: https://data.seattle.gov/Community/Checkouts-by-Title/tmmm-ytt6

Three Gorillion Dollars

kiwifarms.net

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2022

On a side note, I know that Tamsyn Muir has come up in this thread before, but the new book in her series recently dropped and I've been dodging that shit everywhere because it looks insufferable. According to people here (from what I recall) the story itself is actually way less uwuwuwuwu lesbeans 24/7 than tumblr portrays it, but.... is it a recent trend to just advertise things purely catering to the lol so random and gay crowd?

...

I want to be proven wrong but idk, would love some hot kiwi takes from anyone who has made their way through these because I'm super not convinced.

So, first things first - I'm retarded and forgot the password I used for the email for my previous account. I'm also retarded because I read Gideon the Ninth.

Eh, I'm being a bit flippant. Gideon the Ninth is not a terrible book but it isn't a book that is what it's claimed to be. I've heard Harrow and Nona, the sequels, are much more interesting and if that's the case then I'd so so far to claim that what I'm about to say is a deliberate choice on Tamsyn Muir's part. Gideon is just a book that follows the generic YA plotline to a tee. In a future dystopia, a plucky protagonist gets paired with an ambiguous love interest and they need to complete a variety of trials to gain some sort of prestige. I bought it based off the cover quote by Charles Stross (which Muir has since said isn't very accurate, and it's true) and Tommy Arnold's cover art. Arnold must be one of the best in the business. But if it was a ploy on Muir's part, then it's a smart one. Much easier to get something YA published than anything else.

What separates Gideon from just about every other YA book is that it has this fanfictiony/memey tone. I found it really grating because it jarred with the apocalyptic space necromancy setting. I think the second book states that the God-Emperor of Man or whatever was an Internet-brained zoomer or something, hence why the memes survived. But come on. Anyway, the Gideon books have been a pretty decent hit, I think. I'd say this is because they're exactly what they are: very familiar YA stories in a weird setting, with memes and references that undercut that weirdness. The book doesn't really feel like sci-fi at all, which is another reason why the memes feel out of place. It's closer to a whodunit murder mystery than a fantasy adventure. And there's no lesbian necromancers as such. Gideon is a lesbian but she's not a necromancer. Harrow vice versa.

The first chapter is actually pretty interesting, with a swordswoman trying to escape from this crazy necromancy convent type place. But the novel immediately jumps tracks into that generic YA plotline and whatever interest I had just vanished once it became clear what I'd bought. Muir's worldbuilding is really thin and haphazard, the sort where they just throw jargon at you and expect you to believe there's a full-fledged world behind it. Then there's too many characters, some of which overshadow the protagonist, and a plot that doesn't really progress until maybe the last quarter? But that's how these YA plots work, there's always a big infodump and a rush to the finish line.